Under a gray Toronto sky that threatened rain, a ninety-six-year-old woman made a decision that would upend the quiet assumptions of everyone who knew her. Joyce Gladwell, steady as a metronome in most things, had lived in the same house since the 1940s. Its brick façade and clipped hedges gave nothing away, and that was always part of the charm—order, privacy, the comfort of predictable rooms.

But on this afternoon, with a teacup trembling gently in her hand, Joyce told her daughter she was selling. It was time, she said, to let the house go. Then she added a condition that changed the temperature of the room: the basement must never be opened. Not by family, not by buyers, not by anyone. She wanted a promise.

The request hovered there, strange and absolute. Joyce’s daughter agreed because daughters do, especially when the request arrives wrapped in age and urgency. But the unasked questions sat between them like extra guests—What happened down there? Why now?—and Joyce, staring out the window as if the sky had answers, would not elaborate. She moved on to logistics. The tea cooled.

In the frantic efficiency of modern real estate, mystery is a luxury few sellers can afford, but the two sisters who took Joyce’s call the next day recognized it instantly. Gladis and Carla Vaziri—co-owners of a brisk Toronto agency known for moving heritage properties without bruising their history—have heard all kinds of stories: panic sales, estate tangles, divorces that turn keys into weapons.

Yet they would later admit they had never fielded a stranger first conversation. Joyce hesitated at direct questions and replied like someone stepping around invisible objects. She had lived in the house for seventy-two years, she said. It had to be sold now. The basement was not part of the sale.

The sisters arranged a visit expecting heavy drapes and a dust problem. What they walked into felt closer to a museum where every exhibit was curated by a woman with impeccable taste and a stubborn devotion to color. The interior preserved the middle of the twentieth century with a precision that made time feel negotiable: emerald walls framing a living room where a rabbit-ear television perched like a relic that still expected to be switched on; a sun-yellow kitchen gleaming with chrome; a dining room painted in a bold, jubilant coral. In the bedrooms, purple and blush tones softened corners in a way that made visitors lower their voices without quite knowing why. Nothing sagged. Nothing peeled. Even the air felt orderly.

“Mrs. Gladwell,” Carla whispered at one point, trailing her fingertips along the edge of a vanity that somehow hadn’t aged, “how did you keep everything so perfect?” Joyce’s eyes brightened with a private laughter. “A little care goes a long way,” she said. “And maybe a touch of magic.”

Only one jarring note intruded on the careful harmony of the place: a plain, unadorned door at the rear of the hall, its hardware utilitarian where everything else was chosen. A cheap padlock glinted under the hall light like a porthole in the wrong ship. When their eyes drifted toward it, Joyce’s voice gathered unexpected force. The basement was not to be opened, not to be shown, not to be advertised. It was not part of the house. The sisters nodded, the way people nod when their professional instinct is wrestling their curiosity and losing.

In the weeks that followed, the listing became a citywide obsession and a whisper campaign. The Vaziri sisters photographed every radiant room and posted the gallery with diplomatic captions about extraordinary preservation, original finishes, and a lovingly maintained home never before on the market. They omitted the basement completely. The omission did not go unnoticed. Rumors bloomed because rumors are what we grow when facts refuse to.

Some said Joyce had been a low-level intelligence clerk during the Cold War and the basement held reels of film and coded ledgers. Others spun tales of hidden treasure—the kind of wartime stash people never got around to declaring. A darker edge crept into the gossip at the coffee shops and within the online comments sections that always manage to find a sinister angle: a locked door in a very old house is fertile ground for strangers’ imaginations.

While offers stacked up, Joyce’s family packed. Their boxes filled with afternoon light and indecision. At least once a day someone would ask, gently, whether the time had come to tell the truth of the basement. Joyce wouldn’t be moved. She would not unspool the thread of her insistence.

Maybe the knowledge was too heavy to pass along; maybe the warning itself was the last safeguard she could erect against a world that confuses curiosity with entitlement. When the sale entered its final negotiations, Joyce had one more request: the buyers needed to swear they would keep the basement locked. It mattered to her. It mattered enough to say it out loud in a roomful of professionals trained to ignore anything that can’t be notarized.

The family who eventually won the bidding war was polite, eager, and unfazed by the condition. John and Sarah Warren, parents of two young children, fell in love with the house the first time they stood in the doorway and felt their shoulders drop as if the place had made room for them.

They understood spaces with a past; Sarah, a teacher, lit up at the sight of the original cabinetry; John, a contractor, loved the stubborn straightness of the plaster. In the final meeting, Joyce took Sarah aside and repeated the warning one last time with an urgency that made the room vanish for a moment. Sarah promised. They shook hands. The keys changed pockets. The door closed behind Joyce as a final punctuation on seventy-two years of living.

The first weeks in a new house are a blur of boxes and provisional decisions. The Warrens arranged furniture around a life they were still inventing and learned the sounds the old place made—water in the pipes like a clearing throat, radiators ticking themselves to sleep. There was another sound, too, almost more a sensation than a noise: a faint musty breath lingering at the end of the hall where the plain door lived.

At first they attributed it to age. Older houses carry their seasons with them. Then Sarah noticed water staining the living-room baseboard along the wall that backed onto the stairwell. A white bloom of mold appeared in a corner that never got direct light. They could ignore the promise or ignore the creeping damage; one would cost the house, the other their consciences.

Joyce died quietly during those same weeks, the final page of a long book turned without fuss. The shared weight of the vow changed shape. It was still a promise, but its keeper had passed on. John made a practical argument the way people do when they are trying to persuade themselves they are not betraying something bigger: if moisture was invading, inaction would ruin the house Joyce had fought to preserve. Reluctantly, almost ceremonially, he opened the lock, exhaling as if he’d been holding the air for months.

The stairs led into ordinary dimness. Dust motes turned the flashlight beam into a beam of history. At first glance the basement was what basements are—a repository of decades and perhaps a century of domestic life. The Warrens picked their path carefully through layers of furniture stacked into sculpture: a table with lion-paw feet crowded by boxes labeled in an inscrutable shorthand, a sewing machine that looked like it could stitch through sailcloth, the kind of lamp that casts flattering light and reduces anxiety. Against the far wall, the foundation had indeed taken on water; a thin lace of mold crawled in the paint.

They were about to start hauling when John noticed that one bookshelf was pressed tighter to the wall than it needed to be, as if it were hiding behind its own shadow. He tugged at one side and felt the weight release on a pivot. The shelf swung out like a hinge, groaning as if it resented the exercise. Behind it, wood met plaster in a seam, and a small door, nearly flush, revealed itself in a line their eyes would have missed any other day. John lifted the latch. The air changed again—cooler, older, patient.

Inside, space contracted into a room the size of a single generous closet. It was not the scene of the nightmares strangers had invented. It was something more tender and, somehow, more astonishing: a secret archive. Papers were stacked with the kind of care that doesn’t happen by accident. Boxes were labeled in Joyce’s neat hand, a right-leaning cursive that had survived the Gutenberg galaxy without surrender.

There were newspapers so brittle they might sigh into powder if handled carelessly, headlines trumpeting the milestones of a century—the end of war, the beginning of peace, coronations, moonshots, pandemics, elections. There were ration books with coupons still affixed along their perforations, tidy as teeth. There were Victory Bonds, their typography earnest and handsome. Between the artifacts of public life, there was the quiet pulse of private memory: a clutch of postcards, a ribboned bundle of letters, and, most compelling of all, a row of journals spanning decades, their spines creased but not cracked.

Sarah sat cross-legged on the concrete and opened one of the journals because there is a way you lift a notebook when you know the person who wrote it is gone. The first entry began in the late 1930s with the matter-of-fact tone of a young woman who understood budgets in her bones. It recorded the price of sugar and the way the city sounded on summer evenings. It caught the cadence of wartime shortages without melodrama: linings turned, hems unpicked, recipes stretched with ingenuity, friendships measured in tea leaves and shared buses.

Soon entries broadened into portraits of a place that now only exists in books—streetcars that rattled and sang, a city learning to look outward, mothers who watched the postman out the window and pretended not to. Joyce had captured not just her life but the life around her with the kind of attention that makes good historians sit up straighter. Her words were simple and exact. They made scenes assemble themselves in the reader’s head: blackout curtains and ration queues, silk stockings drawn with eyebrow pencil, a victory parade that vibrated the pavement.

The Warrens realized two things at once. The first was practical: the basement moisture needed to be handled immediately or a century’s worth of memory would go soft at the edges and collapse. The second was humbling: the locked door wasn’t a threat; it was a guardrail. Joyce had been protecting not a secret shame but a private museum she never trusted the world to handle with care. She had promised herself to keep it intact. Her last instruction was a continuation of stewardship, not a curse.

They called Joyce’s daughter before they called a contractor. When she arrived and stepped into the small archive, her hands flew to her mouth, not in fear or scandal but in recognition. Pieces of family lore she had only half heard became tactile: the postcard from an aunt who had moved west for a factory job and never returned, the recipe book annotated in her grandmother’s shorthand, the photograph of a street party when victory finally became something you could dance to. She had known her mother was private. She had not understood the scale of that privacy.

Cataloging, when done well, is both a science and an act of reverence. Together, the Warrens and Joyce’s family sorted the collection into logical groupings. They stabilized what could be stabilized with archival sleeves and interleaving tissue. They documented every journal and newspaper, every ration book and bond certificate, digging out context with the help of librarians and a curator from the local historical society. The curator, a patient woman who lit up at the sight of marginalia, arrived with gloves and a tremor in her voice. She called the collection one of the most complete personal windows into mid-century Toronto she had ever seen—ordinary and exceptional at once, the best kind of archive.

Decisions about legacy are seldom easy, but in this case the answer announced itself. Most of the materials would live on in the care of the historical society where climate control and catalog numbers would protect them from time. A selection would stay in the house, not as hoarded treasure but as a small, thoughtful display—a glass case in the renovated basement containing a ration book, a Victory Bond, a single journal open to a page describing a winter morning when the city woke to blackout frost and the sound of distant horns. The rest would be available to researchers and schoolchildren and anyone interested enough to trace a finger over the past without touching it.

Meanwhile, the practical problem demanded attention. Water and mold care little for nostalgia. John brought in a firm to integrate perimeter drains, improve grading, and seal the foundation with materials the original builders couldn’t have imagined.

They ran dehumidifiers for weeks, watched the hygrometer numbers drop into a healthier range, and then began turning the cleared, now-consistent space into a family room that honored the home above it. They kept Joyce’s best pieces not just because they were beautiful but because they felt right where they were—an armchair with a forgiving seat; a lamp that made corners hospitable; a rug woven in colors that negotiated between decades. The display case in the corner became a conversation that never got old. Guests paused, read a paragraph, recalibrated their sense of the house, and moved on differently than they had arrived.

It would be easy to reduce the story to a neat moral about promises and exceptions, how a vow meant to guard a secret came to protect something larger when interpreted with care. But the truth carries a more complicated, more interesting shape. Joyce’s insistence created both tension and preservation. She refused to let curiosity have the last word. The locked door kept the archive safe until a new generation could steward it; the eventual opening saved the house and the materials from a slow, silent ruin water would have written in black fuzz on paper. Both choices—holding and releasing—were acts of love.

The legacy is not only in the objects or in the family room that now hosts laughter where boxes once brooded. It lives in the way the Warrens talk about the house. Their affection is different now; the place is not just where they sleep and cook and mark heights on the kitchen doorframe. It is their portion of a relay.

They are caretakers, not just owners, and that shift in posture changes how a window gets cleaned, how a corner gets dusted, how a story gets told. Their children have learned the phrase “ration book” before most kids encounter it in a textbook. They know their living room stands above sentences written when their grandparents were not yet born. They know winter has been here in heavier ways than the snow outside suggests.

As for the rumors that once animated open houses and comment threads, they evaporated under the wattage of the truth. The secret at the bottom of the stairs wasn’t scandal. It was discipline and memory. It was the labor of a woman who had quietly kept the receipts of a century and put them in order against a day when someone might need to remember how ordinary life survives extraordinary times. The basement door, plain and stubborn, had always kept watch over that task.

Perhaps that was the “touch of magic” Joyce mentioned—nothing otherworldly, just the alchemy of attention. To walk through a house like hers is to feel how care accumulates. Every polished knob is a sentence completed. Every straightened frame is a sigh of relief. The past is not precious because it is gone; it is precious because someone decided it was worth saving while it was still happening.

In the end, the most shocking thing in the basement wasn’t the existence of a hidden room. It was the clarity of intent. Joyce had devoted a portion of her life to building a private archive that made the public story of a city feel personal. She guarded it fiercely in an age that rarely rewards quiet work.

She asked for a promise because she understood how fragile paper is and how fragile memory can be. When the time came, the people who inherited her house learned how to hold both the promise and the paper without breaking either. They did what good stewards do: they fixed the foundation, they told the story straight, and they made room for the next chapter.

Outside, the Toronto sky eventually cleared. Inside, the past and present negotiated a truce. The house breathes better now. Its rooms still glow with mid-century confidence, and beneath them a new room hums at a steady, healthy dryness. In a glass case, a page of Joyce’s journal stays open to the morning she described a city discovering that even in hard seasons, lives go on. In that basement, the air is cool and honest. On the wall above the plain door, the padlock is gone. In its place is a small brass plaque with a single line engraved in Joyce’s tidy hand, copied from one of her letters and chosen by her daughter after a long, quiet afternoon at the historical society:

Keep what matters. Share what you can.

News

“SHUT UP, LEAVITT — YOU ARE TURNING YOURSELF INTO A CHEAP PERFORMANCE IN FRONT OF ALL OF AMERICA.”

They came for the ratings, but they left a wound in the country. It was supposed to be another primetime…

Jimmy Kimmel Blasts Trump at “No Kings” Protest: “Go to Hell!”

Late-night host Jimmy Kimmel made headlines on Saturday after delivering a fiery speech at the “No Kings” protest in Chicago…

They Vanished In The Woods, 5 Years Later Drone Spots Somthing Unbelievable….

At 7:45 p.m. on September 12, 2016, a Seattle rain tapped the windows of a one-bedroom walk-up while Mia Harlow…

Tunnel Was Sealed 120 Years Ago, What They Found Inside Will Shock You!

The mountains above Black Hollow do not rise so much as they accumulate—ridges upon ridges, like knuckles under a scarred…

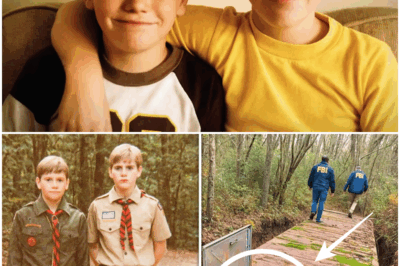

THE VANISHING: The Kinsley Brothers, the Storm, and the Bunker Beneath the Pines

The sky over Oak Haven State Forest went wrong before anyone named it. Sunlight dulled to a bruise; the wind…

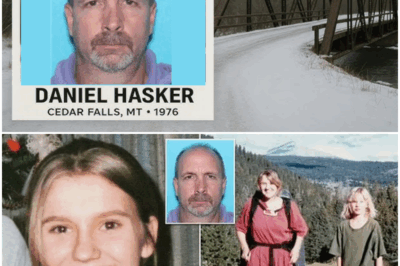

DNA FOUND – 1976 Montana Cold Case | Arrest Shocks Community

A warm lunch, a running engine, and a bridge that kept its secret for decades Under a low-grade December sky…

End of content

No more pages to load