The metal door screamed as it rolled up, a rusted shriek cutting across the auctioneer’s chant and the white breath of a hundred strangers packed tight in a cold October morning in Ohio. It was 2006, and Jerick Ols—twenty-six, broke, and stubborn enough to think that counted as a business plan—stood near the back with his collar up and his hopes down. Storage auctions were for scavengers and luck-drunk optimists. He was both.

“Unit four-eighteen,” the auctioneer bawled. Bolt cutters bit through the padlock. The door ratcheted, the crowd leaned as one organism, and a small kingdom of nothing revealed itself: a cheap pressed-wood dresser with a buckled foot; a tower of unlabeled cardboard; a rolled carpet that breathed mold; the stale, bitter cough of dust.

Jerick’s shoulders dropped. Fuel to haul, landfill fees to pay, maybe a set of rusty golf clubs if God felt like spitting in his coffee. He almost tuned out—almost—until his eye snagged on a hump at the back, a canvas tarp slumped over a shape with a memory of elegance. Round. Symmetrical. Familiar in a way that hit somewhere prehistoric.

He took a step. That silhouette could be a hundred things to a civilian. To Jerick, it was one thing and one thing only.

Fenders, rounded like knuckles. A single curve of spine from hood to tail. A Volkswagen Beetle—late sixties, maybe early seventies—breathing quietly in its grave.

“Fifty,” someone barked.

“One hundred,” another.

Jerick could smell oil in the dust, or else he imagined it, and it didn’t matter. He lifted his hand and found his voice came out louder than his intention. “One-fifty!”

The flea-market reseller with the rat teeth flicked him a glance and sang “Two hundred.”

Jerick didn’t blink. “Three.”

That bought him a frown and silence. The auctioneer’s finger cut the air, the gavel smacked a crate. “Sold. Four-eighteen to the young man with the lungs.”

The crowd drifted. Jerick signed papers with fingers gone numb in the cold, slid his own padlock on the unit, and went to get his truck because ritual mattered. When he came back, the parking lot had the post-storm quiet of a carnival after closing: the echo of voices, the hull of excitement. He lifted the door again. The stale air inside seemed to have thickened in his absence, waiting for him.

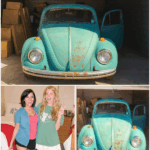

He dragged the carpet out. Hauled boxes into the aisle. The light inside the unit pooled in a cave behind his breath. Finally, he put both hands on the tarp and pulled. It resisted like old glue, then let go with a sigh. Dust motes flared under his flashlight, and the Beetle surfaced like a whale: turquoise under grime, chrome gone dull, tires wilted to pancakes.

He circled the car slow. No dings beyond time’s tooth. No smashed glass. The driver’s door sat a crack open, a mouth that had forgotten its sentence.

Even dead, the thing had dignity.

He scraped the windshield clean where the VIN plate waited and wrote the number in his pocket notebook with a mechanic’s handwriting: blocky, neat, permanent. If the car wasn’t stolen, he might resurrect it. If it was, he’d walk away with a story that ended in beers and a laugh he didn’t mean.

The office smelled like burnt coffee and old receipts. He dialed Darlene at the BMV because Columbus was a big town disguised as a small one, and favors were a currency.

“Run a VIN for me?” he said.

He could hear keys, hear her breath, hear the room around her. Then nothing. Then more nothing.

“Dar?” Jerick asked, suddenly aware of his own heartbeat.

Her voice came back tighter, pitched low like someone had closed a door. “Where’d you get it?”

“Storage auction. Commerce Drive. Why?”

“It’s… not stolen.” A breath. “But it’s flagged. Hard. You gotta leave it. Don’t touch it. I’m calling BCI cold case right now.”

“Flagged for—”

“Hana Sasaki,” Darlene said, and the name put a cold hand on the back of his neck. “Missing persons. ’95. The instructions say notify immediately.”

Jerick set the receiver down like it was hot and walked back across the gravel. The turquoise didn’t look friendly anymore. It looked like a witness.

He stood with his hands in his pockets and waited for sirens that didn’t come because cold-case sirens are paperwork, and by the time the unmarked sedan drifted in and the local patrol strung yellow tape across a square of concrete, Jerick had memorized every flake of rust.

The detective who got out was older than the car and just as stubbornly functional. Gray buzz cut. Windbreaker with the quiet authority of people who’ve worn winds and breakers long enough that no one notices the clothes. He flashed a badge to nobody in particular and came straight to Jerick.

“Mr. Ols?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Detective Elias Vance. BCI. You the buyer?”

“Yes, sir.” Jerick swallowed. “I didn’t… I mean, I thought—”

“You thought you found a car,” Elias said. The old man’s voice was tired but not unkind. “You did fine. Now we let her talk.”

Her. Not it.

The forensic van exhaled a trio of techs and the smell of latex snap. Elias didn’t touch the Beetle. He paced around it like a wolf checks a fence line, eyes scanning, taking in, stripping layers without moving the top one.

He looked like a man who had been waiting for this car to open its mouth for eleven years.

Elias Vance had a laminated folder in a basement that hummed at a certain frequency only he could hear. He could locate it blind and drunk: row 12, shelf 4, box 7, the first file on the left because he had made it so. On the tab: SASAKI, HANA. He could write the case number in his sleep. He had, on the ceiling, at two in the morning.

He remembered the campus in ’95 like it was a postcard that had never been mailed. The design studio lights on at ungodly hours, models of cities on tables, a girl in a pink sweater with a big green H smiling, her student ID clipped to a lanyard that said OHIO STATE. He remembered her parents, stiff with a grief too large to fit in their bodies. He remembered promising them proof of a world that still made sense.

He had not delivered. The world resented promises.

Back then, the theory had been a random abduction. Wrong place, wrong night. The river had been dredged because that’s what you do when you have no idea what you’re doing. The Beetle was gone, too, which bothered him like an itch under a cast. Abductors ditch cars. They don’t make them disappear.

Now here it was, turquoise and patient. He should have felt relief. He felt rage. Not at the car. At the years that had stacked on top of it like concrete.

He walked the boxy little office with the chain-smoker manager who pulled a ledger that was older than some marriages. October 28, 1995: Unit 418 rented. Three days after Hana vanished.

“Name?” Elias asked.

“Robert Foster,” the manager said, like a man reading a stage name from a bad script.

“Address?”

“A vacant lot now. Might’ve been a vacant lot then.”

“Payment?”

“Cash. Ten years in advance.”

Elias blinked slow. A decade buried on purpose. Not panic. Not impulse. Plan.

“What happened in year eleven?”

“Bills bounced back. Phone disconnected,” the manager said, pointing at columns of ghosts. “We defaulted after six months. Posted notice, ran the legal. Then—today.”

A perfect invisibility cloak whose spell expired on a timer. And the car inside, asleep like a myth.

He stationed a uniform at the mouth of the unit and called the lab to baby the Beetle onto a flatbed. “Photograph everything,” he told Dr. Lena Hansen, who had taught half the techs in Ohio to be rude to dust. “Every screw, every smudge. Treat it like a crime scene that’s been on life support since ’95.”

She raised an eyebrow. “Don’t expect miracles.”

“I stopped expecting those in ’88,” Elias said.

He expected work.

They wheeled the Beetle into the sterile brightness of the state impound garage and laid it out under lights like an autopsy’s preliminary prayer. Techs in paper suits moved around it with tenderness. Cameras clicked. Swabs whispered. Vacuum filters hummed. The chalk grid on the floor made the car a topography of the absence of answers.

Results came back like winter: gray and slow and without appetite. No prints worth the ink. No blood. No foreign DNA beyond the lullaby of the obvious: hair fibers consistent with a twenty-one-year-old architecture student and her close circle. The car had been wiped like a conscience.

Elias stood there longer than he needed to, long after he should have left. The fluorescent buzz set his teeth on edge. The turquoise paint looked both jaunty and obscene.

“We’re not going to open it up?” he asked Hana—no, the air, because the only answer in the room belonged to a dead girl and he didn’t ask dead girls to forgive him.

He went back to the file. He ran through 1995 like a cop in a bad dream, looking for the wrong thing on purpose. She’d been brilliant. He’d heard that word too often. People plastered it over loss like a bandage over a bullet hole. But he could see it now in the work: the models photographed for a departmental newsletter, the thin-paper copies of sketches she’d mailed her grandparents because artists are their own archivists when they also carry the burden of being daughters.

The Beetle in the impound garage gleamed in his peripheral vision like an insult.

He needed a new angle. He needed someone who didn’t think like a cop.

He pulled Jerick Ols back in.

Jerick arrived at the impound with a backpack of hand tools and an expression that mixed reverence with the itch of a man about to take apart something sacred. Elias met him with ground rules and the weight of his own skepticism.

“You look,” Elias said. “You don’t touch unless I say. If you find something, you stop. No cowboy.”

“No cowboy,” Jerick agreed, and it was true that he’d been raised on junkyards, not John Wayne.

He walked the Beetle like a doctor who loved old bones—hands hovering, eyes catching where the eye wanted to slide. He checked the heater channels along the floor, the common stash spots. He examined the engine compartment and said, not smugly but like a man saying the weather, “Battery’s disconnected. Whoever parked it wanted it to sleep.”

He lay on his back and eased his head into the cave under the dashboard. From that angle, the Beetle became a city—ducts like alleys, supports like bridges, the glove box a face in the crowd. He was interested in the negative space behind the face.

“Why there?” Elias asked, splayed like a referee watching a strange sport.

“These dashboards have a void behind the glove box,” Jerick said through gritted teeth and a flashlight handle. “Hate to say it, but cops don’t like voids. They’re expensive. They require patience.”

“You calling me impatient?” Elias asked. He was, in movement and metabolism, a patient man. But he liked the kid’s gall.

“I’m saying: you weren’t paid to love Volkswagens.”

Fair.

Elias nodded, and Jerick went to work. It took an hour of cursing and a small quantity of knuckle skin. Finally the glove box came away, and the void exhaled its secret: a rolled cylinder wedged deep, wrapped in butcher paper gone fragile.

“Stop,” Elias said because it was his job. Jerick froze. Elias crouched next to him, breathed in the scent of old paper and dust, and felt the hairs on his forearms lift.

They slid the thing free and laid it like contraband on the table. The paper peeled away reluctantly, and then the room filled with lines—clean, audacious, fluent. Architectural blueprints: not student doodles but the kind of drawings that make rich men say yes and engineers call home.

The title block read: SASAKI, HANA.

Elias turned pages with gloved fingers and a new heartbeat. The tower on the paper twisted like a living thing, a helix of glass and steel that looked like it might unspool into the sky. It was beautiful. It was dangerous. It was familiar.

The last sheet was a charcoal perspective: the tower as a promise. He flipped it and saw handwriting that climbed the page like a person running uphill.

Evidence confirmed. Meeting Prof. Croft. 10 p.m. The site. Final confrontation.

The room narrowed.

Professor Croft.

He could see the man’s face from ’95: elegant in a way Midwestern academics cultivate accidentally and on purpose. Croft had been devastated, cooperative, airtight. Faculty dinner, then home. He had kissed Elias’s theory on both cheeks and set it gently on the shelf.

Elias went from the table to his computer with a speed that surprised his knees. The university database was a fossil he knew how to chip. There he was: Dr. Julian Croft, mentor, adviser, department golden child.

And in the decade since? Not a professor anymore. A brand. A starchitect with a chic firm and a charismatic jawline. He had designed half the Midwest’s ego and won prizes for the rest. The tower that had made him a household name in Columbus was the Aegis, a twisting spear of light that looked—Elias clicked images, clicked again, enlarged, held his breath—like the drawings on his table had come to life in glass.

He needed someone who spoke architect the way Jerick spoke Beetle. He found a forensic architecture scholar in Chicago, a professor with the suspiciously fictional name of Eris Thorne, and sent him scans of the blueprints and publicly available Aegis materials under a pretext that would have embarrassed a lesser liar.

Thorne called two days later sounding like a man who had been dared. “Detective, if what you sent me is what you say it is, then the tower you know is a crime scene. The conceptual spine, the load-bearing innovation, the language of the thing—all Sasaki. The Aegis is not an homage. It’s theft.”

And theft, Elias knew, is a motive when ambition adds teeth.

He checked Croft’s alibi from ’95 with eyes that no longer accepted packaging. Faculty dinner ended at nine. Hana was last seen leaving the studio at nine-thirty. The note said ten at the site. Elias called a retired professor who now lived in Florida because the past likes to move somewhere warm. “He left dinner early,” she said without prodding. “Jittery. Checking his watch.”

He knocked on the door of Croft’s ex-wife, Clarissa, in a Cincinnati complex that looked like it sent its residents coupons for quiet. She was small and fierce with the kind of rage that gets filed down to survive. She didn’t owe him anything. He told her everything anyway.

“The night that girl disappeared,” she said, eyes somewhere else, “he came home late. After midnight. He made me say he was home after dinner. He said he was being targeted. I was twenty-six and stupid. His clothes—” She stopped. “Mud. Dust. The kind that… gets everywhere.”

“Concrete?” Elias asked.

She nodded and covered her mouth like the word might escape.

Concrete. The Aegis had broken ground that week. The deep foundation poured overnight, riverwater in the pipes, slurry in the dark.

Elias saw it in a flash he wished he could unsee: a meeting at ten with promises and lies; rage or fear or a shove that became a blow; a body in a place where men make cities; concrete poured and tamped and smoothed—forever set around brilliance like amber around a bee.

He brought everything to the district attorney, a man with a jawline designed for ribbon cuttings. The DA listened like a man watching a fire move toward his lawn.

“It’s a story,” he said finally. “Compelling. But it’s still a story without a body.”

“We can find her,” Elias said. “Ground-penetrating radar. Scan the columns that were poured that night.”

“You want me to sign a warrant to open a skyscraper because an old detective has a hunch? You want me to light myself on fire in public?” The DA smiled without humor. “You’ve got motive and theory. You don’t have evidence I can take to a press conference.”

Croft’s lawyers called the next day—not Elias, not the Bureau, but the brass—with words like defamation and vendetta and remind yourselves who pays for your toys.

Captain Mendoza sat Elias down and said the words bosses use like Band-Aids. “We can’t move without the DA. You know that.”

“I know we owe a girl more than a shrug.”

“Then bring me a body,” Mendoza said, not even unkindly, which was worse.

Elias had a retirement date on a calendar. He tore the page off and made another plan.

There are two kinds of crimes: the ones you commit and the ones you commit to.

Elias was done asking permission from men who had friends. He called Jerick and met him in a diner where the coffee tasted like punishment and the waitress called everyone “sweetie” with a voice that said she had survived considerably worse men than any detective.

He laid it out. The DA’s fear. The lawyers. The tower. The concrete. The scan.

“I’m in,” Jerick said, because some people jump when the map ends.

Elias had an old IOU with Organized Crime and cashed it for a GPR unit on the kind of handshake that gets men indicted if they’re unlucky. They studied the Aegis security schematics like they were reading a love letter to negligence, found the soft belly—service entrance in the sub-basement, older access panel, less pretty cameras—and picked a Friday night when the building’s heartbeat was slow.

The city was a humming animal by the time they parked three blocks away and shouldered bags that made them look like men moving a piano. The Aegis rose from the sidewalk like a blade. Elias felt the old engine in his chest, the one that had kept him standing all those nights when standing looked like surrender. It revved.

They slid down the alley and pressed themselves to a door that sighed when Jerick teased it with a borrowed keycard and a bypass kit he swore he had only used on legitimate Volkswagens. The lock thunked in a way that made both men exhale. They slipped inside.

The sub-basement was a second world. The air tasted like rust. Columns as thick as tree trunks shouldered the building above. Pipes ran like silver intestines. Their footsteps died a few feet from their shoes.

Jerick assembled the GPR with a reverence usually reserved for bombs. Elias watched the schematic they’d drawn on a legal pad come to life in concrete: columns C4, C5, C6, poured on the night in question, permanently numbered by men with clipboards. They started at C4 because beginnings matter, and spent an hour pushing a radio signal into stone like men interrogating a giant. The screen bloomed with lines that meant nothing and everything, a geometry of density. Nothing unusual.

C5 was stingier. At some point above them a guard walked his route. They killed their lights and tucked themselves behind a generator and became statues while the flashlight beam pawed the room, then moved on. After, they could hear the blood in their ears.

C5 gave them nothing but a slow panic Elias could feel in his molars. C6 was last and destiny and pure superstition and the only one that mattered. They moved the antenna slow. The screen threw back concrete’s boring truth.

Then the image stuttered and changed. An anomaly blossomed near the core—a smooth, oval absence in a matrix that hated absence. Roughly five and a half feet long. Roughly human.

They both stopped breathing. The building did not.

Elias took six photographs of the screen because he believed in the redundancy of salvation. Jerick wiped his eyes with the back of a hand like he’d leaned too close to a grinder. They were about to move when the door blew open and a pair of armed security contractors filled the stairwell with light and directives.

“Hands,” one yelled, gun low because this wasn’t a movie and he wasn’t an idiot.

Elias put his hands up. “Detective Vance, BCI,” he said, badge out, voice flat with authority and the residue of every arrest he had ever made. “Anonymous tip on a potential structural fault. We needed to verify without panic.”

“Middle of the night?” the second guard asked. He wasn’t wrong.

“Would you like to be the one to evacuate a hundred and sixty floors on a Friday at eight?” Elias shot back. He kept his face bored, his heart a drum. He held up the GPR screen. “You’ve got a void in C6. If I’m right, your liability is biblical.”

The guard’s eyes flicked to the image and widened because fear is a universal language and liability is its dialect. “We have to report this.”

“Yes,” Elias said, gentle now. “Please do.”

They escorted him and Jerick to the security desk, where Elias signed a visitor log with the wrong name and left faster than propriety. Thirty minutes later, in a state car held together by hope and maintenance records, he was on his way to the Attorney General’s building because the DA was a politician and the AG had a reputation for hating bullies.

He told the whole story in a conference room that smelled like law and recent paint. He didn’t sell. He laid the photographs down and let the image on the screen speak: a body-shaped absence in a column that held up a man’s lie.

The AG didn’t smile, because some victories taste like pennies. “Get me an engineering team,” she told her chief. “Get me a judge. We’re cutting into a monument.”

The street around the Aegis closed like an iris. News trucks bred in the shadow of the tower. The city asked what it always asks: what’s in it for me, and what is that noise?

Down in the sub-basement, floodlights turned the space surgical. Structural engineers talked in sentences that could support their own weight. Steel braces kissed concrete. Saws ate slow. The building hummed like a thing trying not to think about pain.

The process took three days. Croft gave a press conference between day one and day two on the steps of his glass palace, teeth bare, lawyers flanking him like whetstones. “This is defamation,” he said. “This is a witch hunt by a detective months from retirement. This is a conspiracy theory in search of a headline.”

Elias watched it on a thirteen-inch TV in a trailer underground and felt a calm he didn’t trust. Men like Croft build their lives on the assumption that truth is negotiable. Concrete is not.

On the third day, the engineers hit the anomaly. The saw’s pitch changed. The team stopped being men and became hands. Chipping, brushing, pausing. Silence rolled through the basement like fog. The shape emerged in increments: curve of skull, suggestion of ribs, the intimate horror of fingers. The lab crew sealed the space in a hush that felt like prayer and took her away.

The dental records matched before sunset. The cause of death came with the certainty of autopsy language: blunt force trauma before entombment.

The city gasped. The tower stayed standing.

They arrested Croft at a gala he had thrown for himself. Elias led the troopers across a ballroom where men in tuxedos turned into furniture. The music stopped mid-note. Croft’s smile twitched and broke.

“Julian Croft,” Elias said into a microphone he didn’t need, “you are under arrest for the murder of Hana Sasaki.”

He cuffed him while cameras made his badge itch. Croft didn’t struggle. Men like Croft don’t believe in cages until they’re inside one. The sudden smallness does a thing to their posture.

Trials are long on talk and short on poetry. The state brought a mountain of paper and a chorus of qualified voices. A forensic architect explained, with the polite rage of an academic, how the Aegis wore Hana’s design like a stolen coat. Clarissa told the room about mud and fear. Jerick held the blueprint cylinder in gloved hands for the jury the way you hold a relic. Elias told the story as if facts were stones he could place in a river to help people cross.

The defense tried to sell the jury a fable about genius under siege, about jealous students, about a tired cop with a vendetta. The jury looked at the photographs of the column and did not buy what was not for sale.

The verdict came back fast. First-degree murder. Fraud. A sentence that did not leave room for sunlight. Croft went to a concrete box with bad light. The city scraped his name off buildings and wrote Hana’s where it mattered.

The Aegis was renamed the Hana Sasaki Memorial Building. People argued about whether that was good or grotesque. The truth was it was both: a tombstone you could see from three counties away and a reclamation that said the dead sometimes win.

Elias drove to see Hana’s parents and told them everything. He had done that back in ’95 with a lie he thought was hope. Now he did it with a truth that smelled like concrete dust. They cried the deep, exhausted cry of people whose grief no longer performs for guests. Her mother held his hand and said, “Thank you for getting our girl out of the dark.”

He retired because clocks are indifferent to justice. The brass gave him a plaque and a cake. He left his badge on a desk that suddenly looked like it belonged to a stranger. He found that he had acquired a habit of breathing at the pace of casework. He had to learn how to breathe like a man again.

He visited Jerick’s garage sometimes. The turquoise Beetle sat under lights like a sculpture. Jerick was restoring it slowly, meticulously, as if apologies could be powder-coated. The first time he turned the engine over, it coughed, stuttered, and then found a rhythm that made everyone in the room stand straighter. Machines remember what they’re for.

“What now?” Jerick asked one night when the radio was low and the tools were put away and the smell of hot metal softened the air.

“Now I fish,” Elias said. “Now I build a chair that won’t collapse under me. Now I go sit in a lobby with her name on it and watch people look up.”

He did. The memorial building’s atrium caught light like a hand catches water. Students took selfies on field trips they would misremember as destiny. You could stand under the twist of glass and steel, look up until your neck hurt, and feel a thing in your chest you might call faith if you were drunk or eighteen.

A young woman recognized him there one afternoon. Architecture student. Messenger bag, confidence. “Detect—Mr. Vance? Thank you,” she said simply. “For Hana. For… you know.”

“It wasn’t me,” he said, because the longer you live the less you claim. “The truth was there. We just had to cut it out of the lies.”

He looked up at the spiral. The sun slid through the glass and ran gold across the floor. His breath came easy. Somewhere a column in the sub-basement held a scar they covered with steel and grief, and above that, floors and lives and plans. People were good at living on top of what terrified them.

Elias tucked his hands in his pockets. He thought of the first moment the metal door rolled up and the Beetle took a breath. He thought of the sound of saws three stories under a city and the hush that followed. He thought of a girl who wrote final confrontation with a hand that didn’t shake.

You don’t beat time, he thought. You tell it a story it can’t ignore.

Outside, the tower’s skin mirrored a sky the color of forgiveness. Inside, in a lobby with her name on it, a retired detective finally felt the day end without needing to go back to the office. He stood there until the security guard asked him gently if he needed anything.

“No,” he said, and smiled like it fit. “I have everything I came for.”

News

They Vanished in Redwoods, 4 Years Later Hikers Find a Strange Fungus Infestation at Tree…

The last photo uploaded to the cloud looked like a postcard you’d buy at a ranger station. A wide ribbon…

Before Death, Diane Keaton Finally Opens Up About Her 2 WILD Children…The Shocking Truth

THE LAST CONVERSATION: A MOTHER, A CHILD, AND THE SKY The door clicked softly behind the doctor — a polite…

The Last Hug: A Mother, a Boy Named Léo, and the Promise of the Sky

It was a quiet morning when the doctor closed the door behind him. The click was soft — polite, almost…

Florida Released Hundreds of “Rare Snake Killers” — The World Laughed at First. But What Happened Next Left Scientists and Residents Absolutely Speechless.

When Florida first announced it would release hundreds of so-called “snake killers” into the wild, the world laughed. Experts mocked…

Milwaukee Brewers Fan FIRED in Viral ICE Threat Scandal—Shocking Video Captures Her Telling Latino Dodgers Supporter She’ll “Call ICE,” Sparking OUTRAGE, Social Media Firestorm, and Calls for Justice as Baseball Grapples With Racism in the Stands! ⚾🔥😡📹👇

A Milwaukee Brewers fan has been fired after a now-viral video showed her telling a Latino Dodgers fan that she was going…

BREAKING: Pete Hegseth Stuns America — The Super Bowl Showdown That Shook a Nation

The roar began with a single tweet. “Cancel Bad Bunny. Honor Charlie Kirk instead.” Within minutes, Pete Hegseth — the…

End of content

No more pages to load