She waited almost forty years before she let herself speak without flinching. Not because she needed attention. Not because there was a book deal dangled in front of her or a documentary crew waiting for tears. She waited because silence had been a promise, and for a very long time it felt like the only way to love him properly was to carry the weight he pressed into her hands.

“I never wanted to be accused of capitalizing or exploiting my relationship with him,” Linda Thompson has said, and even in that line you can hear the undertow—how much of her life was shaped by protecting Elvis Presley from the world he both commanded and feared. At 76, the burden has not vanished; it has only become lighter to lift when she sets it down in words.

This is not a tabloid confession; this is a ledger of devotion and damage, of glamour that burned at the edges, of a young woman who walked into Graceland thinking she’d find a fairy tale and discovered instead a pact of care that would define her youth, her future, and her sense of self long after the music stopped.

The first time she met him, it felt unreal the way only Memphis legends can. The summer of 1972 still smelled like pageant hairspray and humid nights when Linda—a fresh 22, “22 going on 13,” she laughs now at the innocence—stepped into a late-night movie screening that Elvis had rented out, one of those private rituals he used to carve out a feeling of normalcy.

Introductions traveled down the aisle like a current: Miss Tennessee, meet the most famous son of your city. He turned, saw her in the darkened auditorium, and the mask of the superstar gave way to that playful, boyish grin. “Hello, honey, where have you been all my life?” he teased.

She volleyed back with the kind of candor that made him blink: “You should have married a Southern girl.” He would quote that line to her for years. It was truth disguised as flirtation, and it told him there was someone in the room who spoke his language of charm but still understood the gravity that came with his name.

Graceland would become her graduate school in fame. She’d grown up in Memphis, but stepping through those gates as part of Elvis’s inner orbit put her on a schedule that belonged to no one but him. Days stretched past midnight; dawn often arrived while everyone else was settling in.

There were always people moving through the house—bodyguards, relatives, old friends, hangers-on who meant well until they didn’t. In that swirl, Linda became not just a girlfriend but a fixed point. Elvis had an unerring instinct for where to place his trust, and for a long while he placed it in her. In the quiet hours after the laughter drained from the rooms, he would beckon her to sit close, to listen.

He could be radiant—singing softly at the piano, improvising jokes, telling stories about Tupelo and the road, all blue eyes and mischief. Then the weather could shift without warning. He would go still, withdraw, pace, stare at the ceiling. The house that looked like a palace to outsiders could feel like a gilded corridor to him, long and haunted by expectation.

It was in those intervals, when the Memphis Mafia had drifted home and the last film reel had stopped spinning, that Elvis handed Linda the secret that tethered her to him. He didn’t dramatize it. He didn’t name it like a confession. He simply let her see it as a fact of his survival, as commonplace as the ornate lamps and the monogrammed towels.

The pills were there—sorted into envelopes and bottles, tucked into nightstands, presented by aides with the brisk competence of routine. He framed them as medicine for pain, for sinus trouble, for nerves, for sleep. Linda wanted desperately to believe the medical storyline.

She was young and raised to be loyal; she believed in the redemptive math of love and patience. But patterns are hard to disguise from someone who shares your hours. She memorized his breathing in the heavy sleeps that followed. She learned the names and shapes of tablets by the way his voice thickened. She understood that this “escape” he leaned on was less a door than a revolving one that never delivered him to the fresh air he was seeking.

Keeping that truth contained felt like an extension of the romance at first, a sacrament of intimacy. Lovers keep each other’s secrets; that is one of the earliest lessons of being chosen. But as the weeks lengthened into months and then years, as midnight conversations turned into systems and systems turned into habits, the sacrament hardened into something else.

The promise of secrecy isolated her from the very people who might have helped her share the load. She learned to perfect light answers for worried friends. She sanded down her face into camera-ready calm at events while a different expression—exhaustion, vigilance—lived in the muscles of her shoulders. She became good at helping him fall asleep and better at staying awake herself.

Love in that house was not only laughter in the music room; it was the choreography of caretaking. People saw Linda on Elvis’s arm and assumed stardust. They couldn’t see the way she hovered at the edge of sleep to count breaths, the way she watched for the small signs—the new bottle on the nightstand, the sharper edge in his temper, the pacing that meant a storm was forming.

Elvis told her he needed her because she understood, because she did not judge. And she did stay. She stayed through the seesaw moods, through the slow narrowing of their private universe, through the moments when tenderness returned and it felt like the two of them might outrun the machine after all.

She believed that if she left, the fragile structure might collapse. She also believed, almost superstitiously, that silence itself was an act of protection, that if she never said the hardest words aloud they would somehow remain less real.

But secrets ricochet. They are not inert; they exert force on the people asked to hold them. By 1976, the force became gravitational. The relationship that had made Linda feel chosen began to make her feel erased. She wanted a future that included daylight—marriage, children, a home that wasn’t constantly being reset to a nocturnal rhythm.

He did not dismiss those dreams; he simply lived on a timetable that rarely allowed for them. His needs were immediate, and they filled the calendar. She found herself measuring the success of a day by whether his mood steadied, by whether he slept, by whether the cycle paused for a moment. She became invisible to herself in the hustle of keeping him visible to the world as the same heroic figure fans needed to believe in.

Arguments came, not as spectacular explosions, but as weary loops. She would ask gently for some part of life that looked like normal. He would nod, promise, deflect, return to the itch that needed scratching now. He trusted her, but the paranoia that shadows dependency crept in. Was she talking to anyone? Could she be trusted not to slip? She reassured him with the stubbornness of a loyal heart, but reassurance cannot compete forever with fear. Doubt, once invited, pulls up a chair.

Leaving him was not a triumph; it was a triage. There was no cinematic scene with a suitcase and slammed doors—just the slow arithmetic of survival. She weighed what she had given against what she had left. She did not stop loving him; she stopped believing that love alone could interrupt momentum.

“Walking away” is too neat a phrase for what she did. She unfastened herself from a narrative that had cast her as a guardian angel, a role no human can play indefinitely without losing pieces of her own name. When she told him, he did not rage. He seemed, in a way that was both heartbreaking and clarifying, to understand. They parted not as enemies but as two people who recognized that devotion and damage were now braided too tightly to separate in the same home.

If Linda carried Elvis’s secret, she was not alone in orbiting its consequences. When Ginger Alden entered his life in late 1976, she stepped into a house where rituals were already scripted. She witnessed details that felt off-kilter: envelopes of “vitamins,” aides delivering mixtures with the soft authority of a nurse, a man whose charisma on stage could wobble, whose memory could glitch under the strain of whatever was coursing through his system.

If you have never loved someone struggling with dependency, it is easy to think that the truth would present itself like a siren. In reality, it arrives by degrees, just plausible enough to pass for “just this once,” and it hides in a thousand administrative explanations.

Ginger watched, worried, tried gentle resistance, absorbed the answers that have soothed so many before: I need it to sleep, I need it for pain, I know my limits. By the time she saw him with an IV in his arm after Las Vegas—a sight that froze her in a hotel doorway—the cycle was no longer deniable. And still, the machinery around him was so practiced that one woman’s alarm could rarely halt the choreography.

The morning of August 16, 1977 remains as stark as an empty stage. A call for the first packet just before seven. Another an hour later. A book in his hand, a promise to read in the bathroom. A companion drifts back to sleep because this is the routine and routine masquerades as safety right up until it isn’t. The particulars have been told and retold, but for the women who loved him—Linda, already gone from Graceland yet forever adjacent in memory; Ginger, there for the last ordinary-seeming motions—the day is not an anecdote. It is the quiet detonation that rearranged the rest of their lives.

When Elvis died, Linda was no longer in his house, but she was still living in the architecture his presence had built inside her. Grief did not ask for her mailing address; it knew exactly where to find her. Part of the sorrow was the man she had loved—the private one, not the global figure. Part was the courtroom of what-ifs that visits anyone who steps away before a fall.

Could she have stayed and saved him? Was leaving a necessary self-rescue or an unforgivable abandonment? Those are not questions reason can settle. They are the sort that live like weather systems, passing and returning, each time with different light.

The world, of course, wanted more from her in those first years after his death. Interviews. Tell-alls. Gossip disguised as tribute. She kept the tightrope: speaking enough to honor him, withholding enough to keep faith with the promise she’d made in dark rooms when the only light was the blue of a television at two in the morning.

She did not frame herself as a savior. She did not re-script history to make herself the moral center. That restraint is its own testimony. It says that love can remain tender even when it has been dragged through the machinery of celebrity and chemical relief. It says that you can forgive a person without forgiving the systems that made their worst choices easy.

From the vantage point of age, Linda has begun to tell the story more fully—not to indict, not to bathe in reflected fame, but to reconcile the two lives she lived: the crown-lit fantasy that strangers projected onto her, and the nocturnal, honest life in which she kept watch over a man who was brilliant and wounded, generous and fearful, gentle and volatile. In her telling there is remarkably little bitterness.

She does not romanticize what nearly broke her, but neither does she let the secret swallow the soft parts. She remembers the way he could turn a room warm simply by entering it, the silly jokes that landed at 3 a.m., the hush when he sang for one person instead of thousands. She can hold those memories without pretending they cancel the nights when her heartbeat climbed because his breathing seemed too shallow.

What do we owe the people we love when their hurt becomes our homework? That is the question underneath every scene in Linda’s narrative. There is no universal answer. Some stay. Some leave. Some tether themselves to an ideal of rescue until they snap. Some learn, slowly, to redefine loyalty as the courage to set a boundary. The culture is hungry for villains and saints; real life gives us human beings improvising under pressure.

Linda tried to hold a secret until it became a stone in her pocket she could not put down. She protected him because he asked her to and because she wanted to. She also lost pieces of herself in the effort. Both truths can be true at once, and grown-up storytelling requires us to let them sit next to each other without forcing a verdict that makes us feel tidier about the mess.

The Elvis that America needed—the icon in white, the pelvis that scandalized a generation, the jawline carved into record covers—was never the man who sat at a bedside explaining why he needed another handful to coax sleep.

In the dissonance between those two versions lived the exhaustion that eventually undid him. Fame offered him the power to bend the world to his schedule; it also installed a glass wall between him and the kind of help that sticks.

Money made doctors easier to find; it made candor harder. The castle was luxurious, yes, but it also kept the wind from clearing the air. Aides were paid to deliver, not to disrupt. Friends loved him and were dazzled by him and were scared to cross him and served him each in the ways they knew how. In such ecosystems, a young woman’s promise can easily become the load-bearing beam of a structure it was never meant to support.

What did Linda learn when she finally stepped outside that house and back into a life with ordinary mornings? That silence can be a virtue until it becomes a wound. That you can be proud of your loyalty and still grieve the years you handed to a secret. That love is not only measured by what you endured but also by the moment you recognize that endurance is not the same as a future. She rebuilt. She worked. She loved again.

She became a person whose story was not a footnote to someone else’s. And yet Elvis never receded into myth for her; he remained stubbornly human in her recollections—sometimes maddening, sometimes luminous, always complicated, always loved.

It is tempting to ask whether it was “worth it,” as if affection can be audited like an account. Worth what? The lost sleep? The youth stretched thin by vigilance? The ache of walking away because staying might turn love into resentment? She does not answer us with neat arithmetic. She answers with the way she still speaks his name—carefully, without spite.

She answers with the gentleness she reserves for the boy from Tupelo who grew up faster than anyone understands and then spent the rest of his life trying to slow the world down long enough to catch his breath. She answers with the fact that she kept his hardest truth long past the point where it could benefit her to keep it.

In the end, the secret she carried is not the twist of a pulp novel. It is the familiar tragedy of a culture that trains prodigies to run on applause and then offers them chemistry when the applause is not enough fuel. It is the story of a house full of people who adored him and could not assemble, together, the permission he needed to want something more sustainable than spectacle. It is the story of a woman who said yes to love and discovered that yes came with a key to a locked cabinet she did not know she would be responsible for guarding.

If Linda speaks fully now, it is not to collapse Elvis into his weakness but to expand our picture of him beyond the poster—into a man who could be both tender and tyrannized by his impulses, both generous and in need of guardrails, both a king and somebody’s frightened darling at four in the morning asking for one more guarantee that sleep would come.

She honors him best not by preserving the myth but by telling the truth with mercy. Mercy for the child who built a throne out of songs. Mercy for the lovers who tried to keep the lights on. Mercy for herself, finally, for the girl who learned too early that love can become a second job and that sometimes the bravest act of love is to stop doing it alone.

So was it worth the suffering? The question feels too small for the life it tries to size. Love, in the house that music built, was not a transaction. It was a weather system that re-arranged furniture and calendars and hearts. It made a young woman feel singular and then made her feel invisible and then, when she left and grew older, made her feel finally like a witness strong enough to tell the story as it actually happened.

Perhaps the better question is this: what do we owe those who carry another person’s truth for so long that it becomes part of their own? If the answer is respect, then Linda Thompson has earned it. If the answer is understanding, her book and her interviews invite it. And if the answer is simply to listen when she finally sets the burden down, then listening is what we owe her now—listening without hunger for scandal, listening the way she once sat up in the dark and listened to him breathe.

News

US Navy Ambushed a Drug SUBMARINE — What They Found Inside Shocked the World

The War Beneath the Waves: How a Silent Vessel Triggered America’s New Maritime Security Era Shortly after 2 a.m. on…

DIANNE KEATON’S FUNERAL, Keanu Reeves Stuns The Entire World With Powerful Tribute!

Los Angeles woke up on October 11, 2025, to the kind of soft, golden light that Diane Keaton used to…

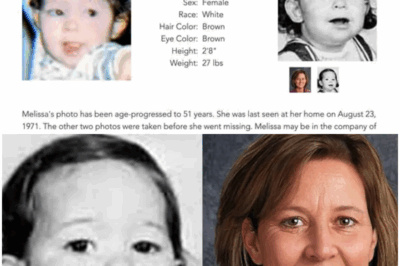

Missing Toddler Vanished in 1971 — 51 Years Later, DNA Finally Brings Her Home…

The heat came on like a verdict that August morning, the kind of Texas heat that makes even the asphalt…

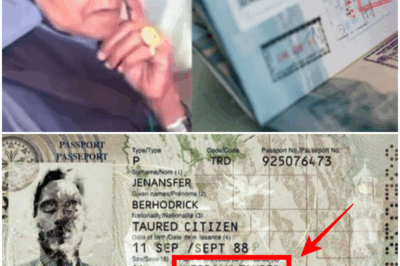

Woman from “another planet” landed in the US, passport stamped with a country that does not exist on Earth: What is going on?

Most Viral Right Now: “The Woman From Another Planet” A bizarre video at John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) in…

Virginia Guiffre memoir details alleged abuses inside Jeffrey Epstein circle

The soon-to-be released memoir from Virginia Giuffre, one of Jeffrey Epstein’s accusers, posthumously sheds light on the infamous financier’s abuses from the perspective of…

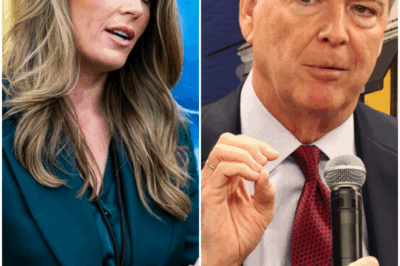

BREAKING: James Comey moves to DISQUALIFY prosecutor Lindsey Halligan, arguing her appointment as U.S. Attorney was not done properly and every action she’s taken in his case is INVALID under federal law.

**WASHINGTON D.C. —** In a city where power plays and legal maneuvering are daily fare, few stories have sent shockwaves…

End of content

No more pages to load