The sun over the Arizona Territory burned like molten iron, swallowing the horizon in a haze of white fire. Everything shimmered, warped, and trembled under the heat—everything except the woman lying motionless beside a wilted cactus. Her name was Sani, a White Mountain Apache warrior once known for her speed, her precision, her fierce independence. But now her legs were dead weight, her body was failing, and the desert had already begun whispering its last rites over her.

Three days earlier, her tribe had left her behind. They had not shouted or cursed her. They had simply looked at her with the distant sorrow reserved for those already gone. A healer had declared that the spirits no longer walked with her after a bluecoat bullet shattered her spine during a raid. In the desert, the wounded were not protected—they were burdens, and burdens died. That was the rule. And so they left her with a half-empty water skin and a knife. The water was for mercy. The knife was for choice.

But Sani was not ready to choose.

Above her, vultures circled lazily, their shadows drifting like dark omens across the blistered sand. She watched them with a mix of contempt and acceptance. “Not yet,” she whispered in Apache, voice like cracked stone. “Give me time. My breath is not finished.”

On the morning of the third day, she reached for the knife. Not to surrender, she told herself, but to take command of a destiny that seemed already sealed. Her hand trembled, sunburnt skin pulling taut over bone. She closed her eyes and began humming the death song her grandmother once taught her—a lament for warriors choosing when to walk into the next world. The melody wavered weakly, more breath than sound.

That was when she heard it.

Hoofbeats.

At first she dismissed it as a mirage—the desert loved tricking the dying—but the sound grew clearer, heavier, multiplied by many. She forced her eyes open. A plume of dust rose in the distance, cutting through the shimmering heat. Six riders, white men, cowboys by the look of them. She tightened her grip on the knife. Death by her own hand was preferable to whatever men like them did to Apache women.

The riders approached, forming a half-circle around her. Some stared in disgust, others in curiosity. One man spat tobacco into the dirt and laughed.

“What do we got here? A crippled squaw rotting in the sun.”

“Might as well leave her,” another said. “She’s half-dead anyway.”

Only one rider remained silent. He was tall, weathered, with a face carved by years of sun and loss. His horse stood steady beneath him, as if used to following a man who didn’t talk unless he meant to. He dismounted slowly, cautiously, and stepped toward her.

Sani raised the knife, ready to open her throat.

He stopped just outside her reach.

“Easy,” he murmured. “I ain’t here to hurt you.”

The other cowboys scoffed, muttering behind him.

“Let her die, Flint. Ain’t our problem.”

But Flint Dawson didn’t turn around. He kept his eyes on Sani—studying her, reading her the way a tracker reads broken twigs and dust trails. He saw more than a dying woman. He saw defiance. He saw the will of a warrior.

He saw someone who still wanted to live.

He looked back at his men. “She’s coming with me.”

The desert fell silent.

One cowboy barked a laugh. “You gone mad, Dawson? That’s a damn Apache.”

Flint’s voice didn’t rise. “She’s mine now—the Apache nobody wanted.”

The men stared at him like he’d lost his mind. Maybe he had. But he walked toward her anyway, and when she didn’t strike, he knelt and offered his canteen. She hesitated only a moment before snatching it from his hand and drinking with desperate, shaking gulps.

“Can you walk?” he asked quietly.

She touched her useless legs and shook her head.

Flint nodded once, lifting her into his arms with surprising gentleness. Her instincts screamed to fight, to claw at his throat, but exhaustion chained her rebellion. He lifted her onto his horse, mounted behind her, and guided the animal west—toward a small ranch tucked against a ridge of scorched stone.

Behind them, the cowboys rode away muttering curses, leaving the dust to swallow their anger.

Two broken souls began a journey neither had asked for.

Two lives already damned by the world found each other.

And neither knew that their salvation—or destruction—had just begun.

Flint’s ranch was small, lonely, and battered by the desert winds. The house was weathered pine, the barn half-collapsed from storms, and the corral held three stubborn horses and a mule that hated everyone except Flint. To Sani, it looked like a sanctuary and a trap all at once.

Flint carried her inside, set her gently on his bed, and stepped back as if giving a wild animal space.

“I’ll bring food,” he said.

She watched him every second, waiting for violence, cruelty, lust—anything she had learned to expect from white men. But Flint moved with a quiet sadness that felt heavier than the walls around them. He cooked a simple meal—jerky boiled with canned beans—and gave her the portion with more meat. Then he sat across the room, giving her distance.

“You’re safe here,” he said.

But Sani didn’t believe him. Safety had never belonged to her kind.

That night, Flint slept on the floor.

And Sani, for the first time in days, slept without feeling the vultures circling above her.

By morning, the world outside had already begun sharpening its knives.

Red Springs—a dusty town two hours from the ranch—didn’t welcome strangers, and it sure as hell didn’t welcome Apaches. When Flint carried Sani into the general store, conversations froze mid-sentence. Women pulled their children aside. Men rested hands on pistols.

Sheriff Tucker, a man carved from fatigue and experience, stepped out of his office with a sigh.

“Flint,” he said quietly, “what trouble have you brought me now?”

Flint didn’t flinch. “She needs supplies. That’s all.”

But trouble didn’t need an invitation. It arrived on horseback wearing wealth like armor.

Clint McGraw—the richest rancher in the county—rode in with six hired hands, boots polished, guns gleaming. His hatred for Apaches was legendary, as was his hunger for Flint’s land.

He sneered at Sani. “That thing is living with you now?”

Flint stared back. “She’s a person, McGraw. Her name is Sani.”

McGraw leaned close, voice dripping poison. “A crippled Apache will bring hell to your doorstep. And if hell comes, don’t you dare come crying to me.”

Flint replied peacefully: “I won’t.”

But peace wasn’t what McGraw wanted.

He wanted Flint’s land. He wanted obedience.

And when he couldn’t buy either, he began planning violence.

The attack came three nights later.

Fifteen men rode out under the cover of darkness, surrounding the Dawson ranch like wolves circling a dying elk. They carried torches, pistols, rifles, and enough hatred to burn a town.

Flint shoved furniture against the doors, loaded every gun he owned, and handed Sani a rifle.

“You ready?” he asked.

Sani nodded once.

“I fight,” she said. “Apache fight.”

The first bullet shattered the window.

Flint fired back.

Fire, gunpowder, shouting—chaos exploded around them. Sani shot through the east window, dropping one of McGraw’s men with the precision of a born hunter. Flint moved like a man possessed—calm, fast, deadly.

But there were too many.

And then, just when the flames licked the edge of the barn, the sheriff arrived with twelve townsmen fed up with McGraw’s tyranny. Their guns cracked through the night, scattering the attackers.

McGraw retreated, cursing Flint’s name.

But the war was far from over.

He had money, men, and power.

Flint had a crippled Apache.

The scales seemed impossibly uneven.

Days turned into weeks.

Flint rebuilt the ranch; Sani learned English; the two formed a bond carved from survival. She cooked, cleaned, repaired clothing, and sharpened weapons. He taught her to read the sky, the cattle, the seasons. They spoke in a mix of English and Apache until their voices blended like desert winds meeting at dusk.

Neighbors brought food quietly in the mornings, ashamed to be seen supporting an Indian but unable to ignore the humanity they witnessed.

Something like peace returned.

But peace in the desert was always borrowed.

McGraw’s next attack was not rage—it was strategy.

He hired professional gunmen and sent them at dawn. Twenty hardened killers, men who shot for coin and didn’t miss. But Sani had been a warrior her entire life, even without working legs. She taught Flint Apache ambush tactics—trench lines, noise traps, false smoke signals, decoys.

When the gunmen arrived, the ranch looked abandoned.

Then all hell broke loose.

Shots from nowhere.

Dust exploding.

Horse screams.

Chaos.

By the time the sun climbed over the ridge, the gunmen were fleeing in panic. Flint and Sani emerged from hiding bruised, exhausted, trembling with adrenaline—but alive.

Two people had defeated twenty.

It wasn’t luck.

It was Apache cunning and cowboy grit stitched together by something the desert couldn’t crush.

Word spread fast.

Some called Flint a fool.

Others called him a hero.

But a few—very few—began calling Sani something she had not heard in a long time:

Warrior.

Not burden.

Not curse.

Not abandoned.

Warrior.

A week later, McGraw came alone.

No guns.

No men.

His arrogance had cracked. His reputation had taken a blow he couldn’t ignore. He spoke quietly, like a man forced to swallow his own pride.

“I’m done fighting you, Dawson. Your land ain’t worth it anymore.”

Flint waited for a trick.

McGraw shook his head.

“But hear this,” he said. “The world’s changing. And a white man with an Apache woman… it won’t be welcomed.”

Then he left.

For the first time, his threat sounded less like anger and more like prophecy.

Months passed.

Seasons shifted.

The desert bloomed briefly, then hardened again. But Flint and Sani grew in strength. She became the heart of the ranch; he became its shield. The town remained divided—fear and prejudice don’t die quickly—but enough people came around to form a thin wall of support.

On a warm spring evening, Flint found Sani on the porch watching the sunset paint the desert in blood and gold. She looked stronger now, fuller, her eyes no longer dulled by despair.

“Flint,” she said softly, her English steady. “Before… I had no home. No family. No sky that wanted me.”

She touched her chest.

“Now I have all.”

He swallowed hard. “So do I.”

And for a long moment, they sat in silence—two souls the world had tried to erase, watching a sky that finally seemed to accept them.

People later said the desert never intended for either of them to survive.

But sometimes the desert miscalculates.

Sometimes the unwanted rise.

Sometimes the abandoned find each other.

And sometimes—just sometimes—the fiercest kind of love is born not from comfort but from the edge of death itself.

No one wanted the crippled Apache woman.

Until one lonely cowboy said,

“She’s mine now.”

And in those four words, two broken lives found salvation.

News

“You Need a Home, and I Need a Mommy,” Said the Little Girl to the Young Homeless Woman at the Bus…

Snow was falling in soft, feathery layers, dancing beneath the streetlights like drifting fireflies when Elliot Monroe first heard his…

A Kind Waitress Paid for an Old Man’s Coffee—Never Knowing He Was a Billionaire Looking …

The downtown café was already alive when the rain began to fall harder, streaking the tall windows with silver ribbons….

Little Girl’s Letter Asked for a Home—Next Morning, The Widowed CEO Knocked on Their Door

The week before Christmas arrived quietly in the small town of Norchester, tucked against the snowy shoulders of New Hampshire’s…

Poor Woman Tried to Pay for One Slice of Bread, The Single Dad CEO Said, ‘Sit Down. Eat First.’

The late-afternoon sunlight cut through the quiet street in pale gold ribbons, slipping through the windows of a tiny sandwich…

“He Was a Lone Cowboy… Until His Daughters Brought Home a Beautiful Apache Woman”..

The sun was sinking behind the mesas when the wind carried its familiar sigh across the Maddox Ranch, brushing against…

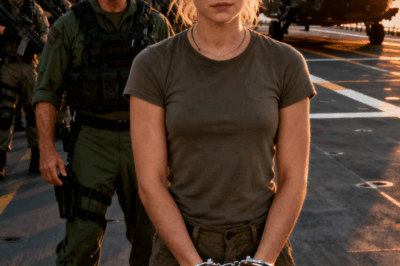

They Arrested Her for Impersonating a SEAL—Until the General Whispered, “That Mark’s Real”

The sun had barely risen over Fort Bragg when Rachel Cross realized the day felt wrong. Two ravens perched on…

End of content

No more pages to load