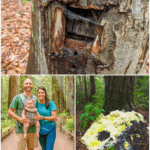

The last photo uploaded to the cloud looked like a postcard you’d buy at a ranger station.

A wide ribbon of light-brown trail cut through living pillars of redwood, trunks straight as gun barrels and older than the idea of America. Kalin Vancraft—shaved head, light beard, an environmental consultant who’d never met a map he couldn’t read—smiled like a man showing off a cathedral he hadn’t built but somehow owned.

Strapped to his chest in a dark gray carrier, his six-month-old daughter peered toward the lens, a pink headband with a tiny bow marking her as a small sovereign in a vast, green country. Beside him, Serena Quaid—designer, cautious heart, long dark hair—leaned in, one arm around Kalin, the other hand resting protectively on the baby carrier. Her bright blue tee and fanny pack popped electric against red bark and green air.

A stranger had taken the picture. You could tell by the framing, the angle—too far to be a selfie, too centered to be luck. At noon on a late-August day in 2013, somewhere off a popular loop inside the Redwood National and State Parks, a family had paused to prove the moment happened. Then they kept walking. And then they disappeared.

By dusk, Serena’s mother, Odilia Hastings, had gone from irritated to afraid. Calls to Serena’s phone rang once, then vaulted straight to voicemail. Kalin’s line did the same—a clean, indifferent jump into silence. That wasn’t like him. He treated communication like rope on a cliff face. If the service dropped, he found a ridge or a bend in the trail and tried again. If he had the baby, he tried twice.

Odilia called the sheriff. The report crawled across desks to a ranger’s hands. That single uploaded photo—a cloud hiccup from a scrap of noon signal—became the tip of a spear no one knew how to throw.

Rangers found the car at the trailhead, parked neat, sun-warmed and dusted with a thin shell of forest breath. No forced entry. No diaper bag on the ground. No notes tucked beneath the wipers. No blood.

The redwoods around them were older than lies. They made their own weather and their own rules. Helicopters skimmed the canopy, their view a ceiling of green. K-9 units snuffled and whined over a floor mat of needles and centuries. Volunteers walked in quiet lines, eyes lowered, radios crackling with the language of hope and grids. The forest absorbed it all and said nothing back.

On day three, Odilia stood near the pop-up tents of the command center, hands pinched white around a Styrofoam cup going cold. A ranger explained about ravines and ferns that could swallow a person’s shadow a yard from the path. The words made sense. The world didn’t.

By week two, the search had the rhythm of a blunt instrument. By week four, rhythm gave way to fatigue and then to logistics. Weather slid colder. Budgets ran out of adjectives. The story joined the country’s long archive of endings that weren’t.

And then it sat there—in the gloved, forgetful hands of time—for four years.

In July of 2017, the forest remembered to breathe.

A small team of mycology grad students from an Oregon university hiked miles past what tourists called far. Their leader, twenty-nine-year-old Xander Zeller, was the kind of meticulous obsessive that science loves and roommates tolerate. He studied fungal regrowth in post-burn landscapes; to him, rot was symphony, bloom was biography.

They stopped near a clearing where an old oak muscled into a redwood neighborhood, a rare interloper that made the place feel slightly wrong. As the students shrugged off packs and fought the slow war with wet socks, Zeller spotted something at the base of the oak that snagged his eye like a burr.

It was a mass—a wet, lumpy sprawl of sulfur yellow and chalk white mottled with patches of oily black, as if someone had poured a chemical foam and walked away. It didn’t look like nature’s handwriting. It looked like a mistake nature was refusing to fix.

He stepped closer and smelled it—putrid and high in the nostrils, the kind of sweetness that meant death doing its true work. He called the others over. They crouched with cameras and debate. Slime mold? A heat-driven bloom? evidence of something buried that fed a city beneath their boots?

Back at a remote field station, a resident botanist peered at the photos, drew a slow breath, and offered the theory that turned curiosity into a path: gases and nutrients from a large decomposing thing—elk, bear—creating an extreme fungal extravaganza. If so, documenting it would be gold.

The next day they returned with core samplers and narrow shovels.

Zeller’s blade cut through the loose topsoil easily. The smell matured from offensive to intimate. Two feet down, the shovel rang dully off something tough that yielded the way roots don’t and rocks can’t.

He brushed away layers with his gloved hand until plastic revealed itself—black, heavy, layered. Agricultural tarp. Human hands.

The air changed. It was no longer the curiosity of students at a specimen; it was the arrested hush of a group at an edge. They cleared space, cut with a field knife through thick seams, and opened a mouth to a dark they would never forget.

Not fur. Not bone of deer. Not the neat architecture of a hoofed animal.

The waxy, clinging remnants of human tissue in the anaerobic jewel box the tarp had made. A skull beneath stiff fabric. The suggestion of a rib cage collapsed on itself.

Zeller’s hand shook dialing the park service.

The site’s remoteness mocked everyone. A forensic team was flown to a clearing miles away, then hiked for hours with cases that clacked like coffins. The bloom around the oak thrummed obscene and bright as they established a perimeter and grimaced into respirators. They moved earth the way you move it when you know the earth is listening. They lifted the sealed body intact and let it keep its secrets until a different room.

Dental records snapped it all into place. The remains were Kalin Vancraft.

Odilia learned the way mothers do—first from a voice trying to be cut stone, then from the sound that escaped her before she made it. The theory that the forest had hidden a lost family evaporated into a colder math: someone had placed him there to be forgotten.

The autopsy answered the question no one had asked. No bullet, no blade, no fractures. The hyoid bone—often the narrator of stranglings—was intact. The cause of death was a door without a knob until the toxicology lab called with an anomaly that felt like a cheat from a different book.

Rattlesnake venom. In the marrow and the preservation soup trapped by the tarp. Enough to end a body within hours if the distance from help is measured in impossible miles.

Rattlers don’t prefer the cool shade of cathedral redwoods, but they exist at the edges, in the heat fugues and dry brinks. Herpetologists, consulted like oracles, shrugged a wary maybe. A bite there was rare but not fantasy.

An accident could explain the death. Nothing about the rest did.

Who wrapped a man so carefully in industrial plastic miles off trail? Who dug deep on purpose and layered the tarp like you layer secrets? Where were Serena and the baby?

Detective Mara Leary had spent fifteen years letting stubborn facts ruin neat stories. She worked major crimes out of Humboldt County with a coffee addiction that had replaced sleep and a habit of standing in doorways as if she could stop bad outcomes by occupying the frame. When the lab report crossed her desk, she pushed away her paperwork landslide and drove north under fog that arrived like a held breath.

The grave site was already an echo. What mattered now was everything that wasn’t there—the tarp that didn’t belong, the plastic that carried more than death. In a world of lost signals and eaten prints, you chase the thing that shouldn’t be in the picture.

Labs teased out what the plastic had kept to itself: a signature of fine volcanic dust embedded in the tarp fibers and in the cling of exterior soil, and the ghost of aged diesel soaked into the plastic’s pores. The tarp itself was a specific grade—UV-resistant, industrial, the kind you use to cover machinery or line a trench, not the blue crinkle you throw over firewood.

Leary asked for maps. Geologists pointed her to pockets of ancient volcanic soil scattered like punctuation across the counties. Agricultural supply chains produced a thin list of rural outlets that sold that exact make of tarp in 2012–2014. Diesel was everywhere, which meant diesel didn’t help until it did.

She filled a wall with layers: soil overlays, supply invoices, parcels with off-grid cabins and old logging camps accessible by spines of track a county refused to maintain. She traced drivable radii from the grave. She overlaid seasonal closures. She let the circles tell her where to knock.

They didn’t go in asking about a four-year-old horror story; in places like this, you don’t lead with ghosts. They went in with fire-safety clipboards and mentions of illegal grows and the practiced demeanor of officials who could, if necessary, become a nuisance again tomorrow.

The places they visited were fortresses of solitude and collections of rusting intentions. People learned to live alone because they meant to or because nobody else would have them.

The lead that mattered sat eight miles from where Kalin went into the earth, at the end of a track that wasn’t a road so much as a promise you had to keep. The property sprawled in a way only neglect can: a cabin folded onto itself with additions, sheds leaning like conspirators, machinery in various stages of surrender, a tractor half-swallowed by blackberry and covered by a sheet of black plastic that looked too familiar.

Wayne Yarrow came to the door with eyes that had learned to narrow without being asked. Late fifties, a beard that remembered meals, hands like the handles of tools. He wore hostility plain. He didn’t want a fire check, a conversation, or a county that remembered him.

Leary’s partner made small talk about defensible space and ember zones while Leary let her gaze do a slow, practiced climb. The soil underfoot was the exact rust-brown of the lab tray from her evidence photograph. The diesel tank wore old stains the color of old sins. Against a shed leaned three rolls of the same tarp—texture, weave, weight—found wrapped around a man eight miles away.

They left with smiles, gravel spitting under tires, and a judge’s warrant in motion before they hit the highway.

They came back in the blue hour before dawn, the air tight with the kind of stillness men like Yarrow called home. The tactical team fanned wide, boots soft, breath white. The door shattered, the room filled with commands; Yarrow went down hard on a splintered floor and cuffed easily, not because he was compliant but because some parts of you know when the tide’s finished.

They searched as if the house were a lie that could be coaxed into telling the truth. The outbuildings offered nothing but years of a life poured into metal and failure. The yard yielded no disturbed earth a human could read. The cabin’s living spaces were cluttered, the clutter not saying anything beyond a man keeping things because leaving them is a skill you learn with company.

Late afternoon, a detective lifted a frayed rug in the kitchen and revealed an outline on the floor—a square that didn’t belong in a house that old, screws that had thoughts about frequency. They pulled the panel. A ladder angled down into breath that smelled wet and wrong.

The root cellar was small, damp, lined with jars whose labels had gone to watercolor. In the far corner, beneath mildewed burlap, the ground offered what people try to keep: a femur smoothed by time, the delicate architecture of a wrist, cloth the color of Serena’s shirt eaten to gray by the years. Dental records were a formality. The fractured hyoid was a sentence.

Behind crates, tucked to be kept and forgotten, was a blue fanny pack with Serena’s life still inside—ID, cards, a grocery list in her hand. Beside it, baby clothes and a hand-stitched blanket with a pattern Leary didn’t recognize.

They sat Yarrow in a room and told him the part of the truth you tell to test the rest. He went through the stages you can predict: denial, indignation, a bad lie about prior ownership, a longer, worse lie about never going off his land. Then he hit the place every man hits when the facts have backed him into a corner with no doors: the confession dressed as a story he hoped someone could swallow.

He said Serena had arrived at his place after midnight, wild and shaking, a baby held tight to her chest. He said she told him how they’d gone off trail to find a quiet spot to feed the baby and how Kalin had sat on a snake hidden in the ground like a bad idea. He said the snake had done what snakes do, and that Kalin had gone gray and gone still fast. He said Serena realized she couldn’t carry a man and a child and went looking for light in the wrong direction.

He said he took a rifle and a flashlight and followed her to where Kalin lay. He said he leaned down and checked for a pulse and felt none. He said he smelled the night, the forest breathing, the chance.

He didn’t call. He didn’t help. He leveled the rifle and herded a woman and an infant back to his house because some men, when the world gifts them a terrible option, choose it like they’ve been practicing. He admitted to what he did next in language that sanitized and avoided and still landed like a brick: he restrained Serena in the cellar and raped her. In the morning, he decided he wanted a version of the future where consequences were imaginary, and he strangled her with hands that had built and broken and coaxed engines back to life.

He wrapped Kalin in plastic—his plastic—and buried him off trail near the oak because it was far and soft, because he thought the forest keeps secrets. He said he made tea. He said the baby would not stop crying.

When Leary asked him what he’d done with Isela, Yarrow’s face did a thing she cataloged and refused to decode as anything human. He said he drove south. He said he crossed into Mexico. He said he handed a baby to an orphanage in a small town in Oaxaca and gave a name that wasn’t real. He said he couldn’t kill a child and wanted a clean kind of mercy.

Leary didn’t believe in clean. But border crossing logs showed his truck southbound a week after the disappearance. Receipts with Spanish dates were wadded in a drawer. The hand-stitched blanket matched a regional style you could buy in a market near the town he named.

The search for Isela shifted to a maze of paper and memory. Four years is a lifetime when you are one. Orphanage records blurred human detail into institutional script, and the men who ran those places were not always better than the men who found them. Requests went out. Photographs were compared. A dozen girls with eyes you want to call familiar were held up to the light and returned to their lives with their names intact. None of them was Isela. Or else she was all of them, which is what mothers know better than detectives.

Yarrow took a plea to avoid a trial that would have burned what was left of a county’s patience. Life without parole. He sat in prison like an animal learns to sit when the cage is the world. His confession became the official story, and like most official stories, it was both too neat and the only one anyone had.

Odilia brought Serena’s ashes home in a box that a funeral director insisted was tasteful. She brought Kalin’s too, because grief doesn’t do in-laws. She placed them on a mantel she dusted twice a week without seeing. The house filled with flowers that wilted on a schedule and cards that said the right things with the wrong certainty. The space around the word granddaughter remained a country you could not occupy with language.

On the one-year anniversary of the discovery under the oak, Odilia stood at the edge of a grove off a different trail with Detective Leary. The air was cool, the way these groves make it even in August. She wore a jacket she didn’t need and held a thermos she didn’t drink.

“Tell me there’s a chance,” she said. She didn’t mean in court. She meant in the world.

Leary watched a shaft of light climb a trunk like a slow alarm. “There’s always a chance,” she said finally. “I’ve learned not to insult mothers by pretending to know the size of it.”

Odilia nodded. “People bring candles to the trailhead,” she said. “They leave shoes.” She almost laughed. “Baby shoes.”

Leary had seen candles and shoes. They were offerings to two gods who never answer: Memory and Time.

“We keep looking,” Leary said. “The cross-border unit talks to Mexico every week. The case is open. Her file sits on my desk where I bump it on purpose.”

Odilia closed her eyes. “Don’t put it away,” she said, and she meant, Don’t put her away.

In the years after the arrest, the redwoods did not change in the way we need them to when bad things happen. They stood, and in standing they gave the illusion that endurance is justice. The park added a small sign to a kiosk near a popular loop that asked visitors to stay on marked trails and told a story about safety written in the past tense. Strangers stopped and read and looked at their children with new caution. They still stepped into ferns for photos.

Xander Zeller finished his dissertation on fungal bloom anomalies in nutrient-rich micro-sites and never again used the phrase “nutrient-rich” without a wince. He spoke once at a conference about the ethics of fieldwork when your shovel finds more than science; the question-and-answer session turned into a grief circle in lanyards and name tags.

Detective Leary made friends with the case file the way you do when it’s the kind that refuses to stay put. Tips came and went. A woman in Texas sent a photo of a four-year-old with a pink bow that did a very cruel thing to Odilia’s heart for a week. A man in Oaxaca wrote a letter in hesitant English about a girl at a market with a laugh that felt imported. Leary followed all of it until following became honoring rather than progress.

Yarrow died years later in a prison infirmary that smelled like bleach and unfinished stories. His last recorded words to a chaplain were a quote from Scripture that fit him poorly. He never retracted the thing he said about the orphanage, which might have been the one part of his confession he’d carefully engineered to force the world to grant him a sliver of a way out. Men like him always want the last kindness to be a line in their own biography.

On a cloudless afternoon the following spring, Leary parked in a dirt lot off Bald Hills Road and walked until voices thinned. She reached the oak that didn’t belong and stood where a bloom had once announced the secret underneath. The soil had settled. The forest had taken back its shape. You’d never know what had been there unless you knew.

She crouched and pressed her palm to the ground. The gesture felt trite and true at once.

At home that night, she pulled the case file and opened it to the photo—the one that had started everything and promised nothing: a man, a woman, and a baby beneath a sky of branches, the camera held by a stranger whose name had finally found its way into the report. She traced a finger along the edge of Serena’s smile and stopped at the pink bow.

She imagined Isela somewhere in a sun-struck country she’d never been, hair grown in, hand in someone’s hand who wasn’t the right one but could be gentle. She imagined a girl who had learned a name that didn’t belong to her and wore it with the kind of grace that children are forced to learn.

She imagined a knock on a door five, ten years from now—a kindness with a badge, a test in a sterile room, a call in the night that made a mother’s knees go weak in the kitchen. She let herself believe in a version of the future that used words like reunion and miracle without apology. Then she let the belief go because you can’t work on hope alone.

Leary put the photo back, closed the file, and set it on the corner of her desk where it would be in the way tomorrow and the next day and the next. She turned off the lamp and let the room go dark.

Out in the redwoods, the giants kept their own counsel. They grew in rings and weathered lightning and stitched fog into water. They made space for life and, when asked, for death. If they hoarded the rest of the story—the hour between the last photo and the first terrible choice, the exact shape of a path that veered wrong—they did it the way old things do: without malice, without intent, as witnesses to a human drama that keeps choosing itself.

Under their shade, hikers’ voices rose and fell, and cameras clicked, and babies slept against the steady hum of hearts that did not know yet what they would have to carry. And somewhere south, in a town lined with color, a girl with dark hair and a pink ribbon—not a bow, not the same, but something chosen—looked up at a sky that had never known the redwoods and laughed at a joke told in a language that had become hers, a sound bright enough to cross a border if sound could do that.

It couldn’t. But mothers can. Detectives try. Forests wait. And sometimes—quietly, stubbornly—the truth blooms where you least expect it, bright as sulfur, strange as grace, impossible to ignore.

News

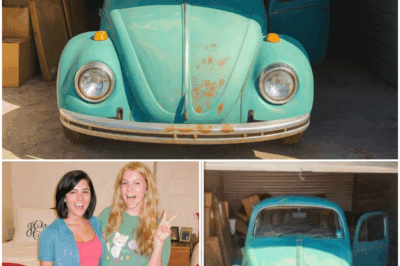

College Student Vanished in 1995 – 11 Years Later Her Car Appears in a Storage Auction…

The metal door screamed as it rolled up, a rusted shriek cutting across the auctioneer’s chant and the white breath…

Before Death, Diane Keaton Finally Opens Up About Her 2 WILD Children…The Shocking Truth

THE LAST CONVERSATION: A MOTHER, A CHILD, AND THE SKY The door clicked softly behind the doctor — a polite…

The Last Hug: A Mother, a Boy Named Léo, and the Promise of the Sky

It was a quiet morning when the doctor closed the door behind him. The click was soft — polite, almost…

Florida Released Hundreds of “Rare Snake Killers” — The World Laughed at First. But What Happened Next Left Scientists and Residents Absolutely Speechless.

When Florida first announced it would release hundreds of so-called “snake killers” into the wild, the world laughed. Experts mocked…

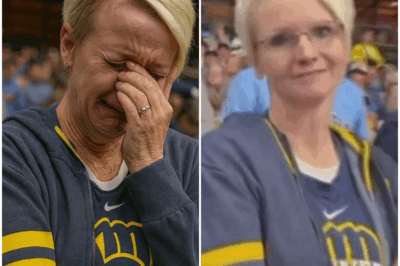

Milwaukee Brewers Fan FIRED in Viral ICE Threat Scandal—Shocking Video Captures Her Telling Latino Dodgers Supporter She’ll “Call ICE,” Sparking OUTRAGE, Social Media Firestorm, and Calls for Justice as Baseball Grapples With Racism in the Stands! ⚾🔥😡📹👇

A Milwaukee Brewers fan has been fired after a now-viral video showed her telling a Latino Dodgers fan that she was going…

BREAKING: Pete Hegseth Stuns America — The Super Bowl Showdown That Shook a Nation

The roar began with a single tweet. “Cancel Bad Bunny. Honor Charlie Kirk instead.” Within minutes, Pete Hegseth — the…

End of content

No more pages to load