At 7:45 p.m. on September 12, 2016, a Seattle rain tapped the windows of a one-bedroom walk-up while Mia Harlow refreshed her text thread for the tenth time. Her brother Caleb had promised a check-in from the trail at six—he was meticulous that way, the kind of backcountry hiker who laminated maps and set backup alarms—but the message never came.

The last photo, stamped 9:15 that morning, showed five friends at the Easy Pass trailhead in Washington’s North Cascades National Park: Caleb in the center, grinning beneath a knit beanie; his best friend, Dylan Reyes, looping an arm around him; the irrepressible jokester, Marcus Lang; and behind them, two women half-hidden by tall firs, graphic designer Sophia Kaine and ER nurse Riley Brooks. They looked like the archetype of a Pacific Northwest weekend: damp fleece, bright eyes, a group thread called “Trail Snacks.”

Within hours, a ranger at the park’s Stehekin station opened a missing-hikers file, then another, then a rolling list: five experienced backcountry campers, ages twenty-six to twenty-nine, last seen entering a 20-mile loop that threaded high passes, braided glaciers, and one notorious side canyon locals called Devil’s Gulch.

By dawn, helicopters beat gray light into ribbons above the subalpine ridges while ground teams spread into a landscape that excels at swallowing sign. The blue Ford van the group had driven up from Seattle remained parked and neatly locked at the trailhead. Inside the command tent, a map bristled with grease-pencil Xs and lengths of red string. Outside it, parents and siblings gathered under a canopy, hands around paper mugs of burned coffee, blinking through shock into a cold that felt personal.

The North Cascades are defined by something more than awe: they are an architecture of absence. Valleys shear into sudden ravines, streams turn testy with rain, microclimates roll weather downhill like marbles. A person can be ten yards from a trail and vanish. For twelve days, searchers grid-walked slopes and talus fields, shouted names into wind that carried sound away in a breath.

The operation swelled to include volunteers, dog teams, and a borrowed infrared chopper from Oregon. They found nothing—no torn fabric in larch needles, no scuffed dirt at a switchback. As the days tacked into a second week, a ranger tacked a final page to the clipboard: search-to-limited, pending new information. The case slid, as so many in these mountains do, into a file drawer of unanswered things.

It might have stayed there, but for a chance sightline five years later.

A Click in the Fog

On a crisp July afternoon in 2021, a wildlife photographer named Jordan Hale returned to a rented cabin outside Marblemount with three batteries at red and seventy minutes of drone footage of elk herds migrating along a treeless shelf.

He offloaded the files, toggled through thermal overlays, and froze at a smear of blue where there should be only granite and vine maple: a tent fly, sun-chalked, half collapsed into moss, and beside it a shine that read like chrome.

Hale scrubbed backward and forward, then paused on a structure his brain kept trying to call a cabin. A second pass clarified the geometry: a boarded mine entrance, slumped into brush. Coordinates pulled from the drone stamp placed the scene deep inside Devil’s Gulch—a canyon so steep and badly timbered that even veteran rangers cautioned one another to avoid it.

Hale did the next right thing. He backed up the footage, drove to the ranger station, and handed his hard drive to a woman who had spent a quarter century becoming a skeptic of miracles.

Ranger Elena Vasquez’s hair had gone silver over two and a half decades in the park. Files in her office displayed a taxonomy of mountaineering errors and bad luck: a slip, a storm, a snow bridge that looked more solid than it was. “Most disappearances here,” she says now, “are weather plus terrain plus a moment’s bad math.”

She looped the drone footage on a dusty desktop monitor, leaning forward as the camera nosed along a gorge stitched with alder. The blue flare of a tent popped and resolved; the burred rectangle of lumber and rust behind it sharpened into an old adit. Vasquez exhaled and picked up the radio.

The next morning, a technical team stood on the lip of a canyon that looked, in the absence of scale, like a stitched wound. They rigged anchors into firs and rappeled through damp air toward a bottom they couldn’t see until they were in it. The tent, once royal blue, had faded to a pastoral grief. Inside: a stove bent into a question mark, a bandanna, a blister kit, a keychain with an enamel horseshoe—Dylan’s, according to his sister—and a spiral sketchpad swollen with rain. On the first dryable page, in a clean, graphic hand: a ridge line, a mine portal, the inside of a shaft lit as if by memory.

The cabin was not a cabin. It was the collapsed mouth of a nineteenth-century mining claim. When the team pried boards loose, ghost-cold air climbed out around their knees. Light from headlamps made cones in dust and picked out the minimal geography of an emergency life: flattened cans stamped with dates from 2016, a nest of evergreen boughs matted to the shape of human rest, and—most startling—names ragged into the damp wall with a knife tip: CALEB DYLAN MARCUS SOPHIA RILEY HELP US. The words were not a scream; they were blunt fact to be recorded before it was too late.

Hope returned like a biological reaction. It would not last.

The Avalanche That Wasn’t on the Forecast

Meteorological records dug by a Forest Service analyst documented a freak September system that had dropped snow on high passes that week. The North Cascades can produce avalanches in shoulder season when new snow layers marry poorly with old ice. A torn page from Marcus’s notebook, recovered in the gulch, told the story in four shaky lines: “Day 3. Avalanche blocked the pass. Fell into gulch. Injuries bad. No way out.”

From that note forward, the narrative splits into two timelines—one for the outside world, with press conferences and dwindling leads; another for the five people who fell off the map into a place so deep and timbered the map barely acknowledged it.

Inside the mine, the group did what prepared people do. They triaged injuries: Dylan’s ankle—a clean break likely suffered in the slide; Caleb’s ribs—fractured; Sophia’s wrist—snapped in a fall and splinted with a tent pole. They inventoried food and put the strongest on water runs to a creek that bounded the canyon in a loud, unreachable seam. They kept a fire going as long as smoke wouldn’t draw attention. They recorded days on an interior board, then the rock when ash smudged the paper. Failing out was not possible. The gulch’s slopes rose like walls; the only egress ran through a chute of brush and slides that had taken them down like a hand.

On Day 47—calculated later by the tally marks on a pane of plywood—they heard voices. Marcus’s next entry wobbles into another hand: “Day 48. Two men found us, took S+R. Said they’d get help. Caleb says no trust…” The writing trails into a gouge.

It is here, investigators say, that the Lost Five ceased to be a purely wilderness story.

Squatters in the Gulch

Rangers had long traded rumors about Devil’s Gulch: of poached elk quartered by headlamp, of meth cooks in borrowed camp trailers parked on logging roads, of off-grid drifters who laced traps along the creek. Park records showed sporadic illegal activity but little prosecution—the gulch was difficult to police and, short of a major violation, easy to ignore when budgets were thin.

Following the mine discovery, Vasquez asked a retired colleague to help her reconstruct the subculture that used the canyon as cover. A single name rose from a stack of cautions and near-miss reports: Leon Carver, forty-something, listed in local law enforcement systems as a trespasser and occasional assaulter, capable with a rifle and quick to move camp when attention sniffed him out. His sometime companion, a woman known only as Tessa Hall, appeared in one blurry roadside photo.

It took a poacher’s snare to draw a line from rumor to fact. A volunteer flagged a trap near a creek on the gulch’s east wall, its cable crimped with a signature method a state game warden had documented in a separate case tied to Carver. Not far from the snare, searchers found a lean-to with a brand of cigarette butt Carver favored and, tucked under a collapsed ridge of fir boughs, a scarred map annotated with pencil crosses over cave mouths.

A cave expert in the team traced one route to a narrow fissure north of the mine. Inside, investigators found a space the size of a micro-apartment—dry, warmer than outside—and the remains of a long occupation: a cache of canned food dated 2016 and 2017, a bedroll, a hairbrush threaded with blond strands consistent with Sophia’s color, and a soaked notebook whose first page bore Riley’s small, careful script. “Day 90. They won’t let us leave. Say it’s safer here. L + T watch us. Planned to run.”

No entry in that notebook extended past the fall of 2018.

Tucked beneath the bedroll, the team found something else: a spent .38 slug, later matched to a revolver recovered in a 2020 raid on a poacher’s camp outside the park. The gun had once been registered to Carver. A shallow grave outside the cave held two skeletonized bodies—one male, one female—each with a bullet wound. Forensic anthropologists were able to align the dental structures with DMV files and, later, DNA: Leon Carver and Tessa Hall had died within months of the mine’s first makeshift tally. Whether from a power struggle or a fracture that severed their ability to hold captives, the effect was the same. A window opened.

Sophia and Riley took it.

Survivors

The human body is not equipped for a two-year slalom through fear and deprivation, yet this is what the record suggests: that two women endured a captivity that began with ersatz rescue and turned to forced labor—digging, hauling, running errands under watch—before a storm—wind loud enough to drown a footfall, rain sufficient to wash tracks—allowed them to slip the cordon of a dying camp. Riley’s nature—organized, medical—shows in the entries that follow. “Left the cave,” she wrote in October 2018, “S hurt bad. Wrist and ribs. Left her at road. Kept going.”

For days, then weeks, the outside world had moved on. Search money dried up. Media T-packs left for fresher tragedies. Mia Harlow quit her marketing job to spend her savings on private teams who made sweeps through the park before the snows came, but no one aimed into a canyon for which there was no safe approach and nothing but speculation to recommend it.

What pulled the Lost Five back into the center of things was not a breakthrough at the gulch but a woman who walked out of it and forgot how to speak.

In August 2019, Spokane police responded to a call about a woman staggering near a rail yard, mud caked to her calves, fingers cracked and white with old frostbite. Hospital staff wrote her in as Jane Doe, age late twenties, mute, malnourished, with a poorly healed wrist fracture.

She shed no tears. She reacted to nothing but a hand placed in her hair—flinched, then quieted as if from an old memory of care. The hospital stabilized her, then transferred her to a long-term facility that specializes in unmoored lives.

It took the devil’s bargain of a viral story to draw a line between her and a five-year-old disappearance: after the drone discovery, a producer searching backward through missing persons flagged the facility’s report of a silent woman who matched Sophia’s description. Mia drove east with a photo of the five at Easy Pass. When the picture slid across the cafeteria table, the woman’s gaze moved from face to face and stopped. “Riley,” she said. The room went still.

DNA confirmed the identification: the Jane Doe was Sophia Kaine.

Questioning went slowly and then, suddenly, all at once. Sophia’s language returned in fragments—colors first, then place words, then names. She could not describe the men beyond hard nouns—gun, rope, dig, cave—but she recognized the mine photo, and when an investigator traced a finger along a ring-bound sketch of a canoe, Sophia tapped the paper fast, a child asking the adult to rush.

Within a week, rangers were in a canoe off Crystal Basin following a shoreline that held more shadow than water. They found a shallow grave in a cave, curled bones, a nurse’s ID badge, a silver locket with a photo of a man inside, and a single line in the cramped script of someone writing with their last strength: “If found, tell them I tried. East Ridge cabin.”

The remains were Riley Brooks. She had made it farther than anyone guessed—and the diary she left in a wrecked cabin described a final sprint of improbable grit: a canoe scooped from reeds with a hull scratched “RB,” a stash of supplies in a log shed, a night run to draw pursuit away from Sophia’s hiding place. The last entries dwindle to weather and hunger. “Cold. Lost. Help me.” She died—likely from exposure and a systemic infection—within days of putting down the pen.

In the mine complex, forensic teams exhumed three more graves shallowly covered by damp dirt. Dental records and DNA identified the men: Caleb, Dylan, Marcus. Each showed injuries consistent with a slide and a fight: fractures, concussive trauma. One skull bore a blunt-force blow investigators believe occurred during a confrontation with Carver. “It is a wonder,” the state anthropologist told me, “that we have any story at all, given what time and water do to bone.” That we have one is testament to a set of small stubborn acts: a drone battery that held one more minute, a ranger who couldn’t quit a file she’d already closed, a sister who refused to leave the park when the press vans did.

The Ledger of the Gulch

Cases like this collapse into headlines—the drone discovery, the cave, the locket—yet the truth is sewn as much by paperwork as by drama. In a storage unit in Bellingham rented under a Hall alias, investigators found a ledger of small, mean transactions: ounces of placer gold sold to a man who asked no questions; ammunition purchased with cash; a notation for “cans” and a price that matched a bulk purchase of soup and beans at a warehouse store. A photo—Tessa pointing into a hole, Leon blurred behind her—helped date the regimen of forced labor. “We heard the rumors about illegal mining for years,” says a federal land agent who worked the case. “What we didn’t know was that the myth had grown teeth.”

The gulch had protected them. It had also trapped their criminals. When Carver and Hall turned on each other—ballistics tie both to the revolver—their off-grid ring frayed. Hall died in the cave; Carver, outside it. It remains impossible to untangle their precise motives in real time. Poverty is no excuse for brutality, but context matters: people living at the edge of legitimacy often act quickly, desperately, badly. The women were assets until they became liabilities. Then they ran.

The Aftermath

In a quiet wing of a Spokane facility, Sophia relearned how to be inside a day. She slept with the light on for months. She flinched at the scrape of chairs. But she also began to draw—first a simple line, then a mine entrance, then a canoe with a hull half-hidden by reeds. The drawings turned into a blog under a title she chose—“Surviving the Gulch”—and then into a series of fundraisers for a nonprofit her friend Mia started in the wake of the discoveries.

Echoes of the Lost privileges practical over poetic: drones outfitted with thermal cameras; grants for satellite messengers and training for rural departments; a stipend for families who can’t afford to keep a motel room near a search zone. Within its first year, the program funded a ranger outpost in Devil’s Gulch and helped locate a climber pinned under an icefall on Shuksan. The climber—thirty-two, a teacher—came to the memorial plaque at the Easy Pass trailhead and left a note that read, simply: “You saved me.”

Policy moved, too. The park formalized a coordination protocol with county and state agencies for illegal activity in remote corridors and funded seasonal patrols in the gulch. The Forest Service updated maps to flag historic shafts and adits, and a small team is digitizing nineteenth-century mining claims to overlay against modern topographical data—an information sheet that can keep a rescuer from stepping into a hole hidden by salal. A state lawmaker, moved by a mother’s testimony, wrote a bill to expand the Cold Case Task Force’s purview to wilderness disappearances.

Closure is a luxury word in the mountains. Families said goodbye in three different places: a meadow near Easy Pass where a plaque lists five names, though only two people lived to read it; a low room in Spokane where a sister pressed her forehead to another’s and breathed; a cave where a retired ranger—Elena Vasquez left the uniform shortly after the case closed—touched the rock above a fire scorch and said into the silence, “We found you.” That none of those moments return a life is the central obscenity of loss. That they exist is the central comfort of community.

A few questions persist. In 2025 a ranger flagged a spent .38 casing near the overhang where Riley left her last cache, matching the weapon that killed Carver and Hall—evidence that someone, sometime, returned. A boot print at the cave, small and newer than the rescue team’s, suggests a visitor stood where the women once hid. Whether a poacher, a hiker, or a straggler from the gulch’s old network, no one can say.

An anonymous letter arrived at Echoes of the Lost with Riley’s clipped obituary and three words in block letters—“She was brave.” The postmark was Spokane. Investigators opened a supplemental case file, but trails grow cold fast in big country. Perhaps the sender was a witness who saw a figure limping down a road in 2018 and felt too ashamed to have done nothing to sign a name. Perhaps they were a ghost of that world, living, as the gulch taught them to live, without proof.

What Remains

When I meet Mia and Sophia in late summer, they are two women in their thirties sharing a kitchen table scratched by keys and coffee mugs, a houseplant tilting toward a northern window. The apartment holds the residue of the life that keeps moving: a stack of padded envelopes for Echoes mailings, a half-finished painting of firs pressed so close together they read as shadow, a vase of wildflowers picked on a trail Sophia can finally walk again without looking over her shoulder.

We speak for two hours and say the word “gulch” only twice. Mostly we speak about ordinary rescue: naps, birds, baths hot enough to make palms pink, private jokes that survived the scrubber of time. When I ask Sophia what drew her back to drawing, she shrugs. “Pictures,” she says. “They hold things words can’t.”

Before I leave, we drive to the trailhead. The plaque is dark granite set into a boulder, polished enough to reflect a face. Others have been here: a coil of climbing rope left like a wreath, a rubber band ball bound tight and placed on the flat stone ledge, a faded bandanna clipped under a rock so it won’t blow away. The inscription reads:

IN MEMORY OF

CALEB HARLOW • DYLAN REYES • MARCUS LANG • SOPHIA KAINE • RILEY BROOKS

LOST, AND FOUND IN SPIRIT

NORTH CASCADES NATIONAL PARK • 2016–2021

Sophia touches the last two words with the back of her fingers. “Riley saved me,” she says softly; then, more firmly, “She saved me.” Some sentences are prayers in plain clothes.

Far up-canyon, wind slips a long note through fir needles. It sounds, for a second, like voices, though it is only air. The mountains keep their own time. They keep their secrets, too, until someone with a drone and a hunch and a ranger with a stubborn streak interrupts the calculus. Not every disappearance will unspool like this one did—into shafts and ledgers, diaries and rescues—but the lesson travels: search longer, map better, listen hard to the people who refuse to stop asking the same question. Not all mysteries end. Some are simply carried better.

On the way back to Seattle, a weather front slides over the Highway 20 corridor and the sky becomes the color of old pewter. I pull off at a turnout with a view into a valley that could be any valley here—clouds brewing in bowls like steam, a river soldering brightness into dark rock. In the rearview, a ranger truck noses onto the shoulder, the driver thumbed into a phone, another case, another call. A plaque in the gulch reads that the five are not forgotten. It is both promise and obligation. The work of remembering is, like most work worth doing, never finished.

News

“I knew the moment I opened that message… they weren’t just trying to scare me—they wanted to break me,” said the Oklahoma student, describing the chilling late-night threat he received after publicly honoring Charlie Kirk.

They did not simply leave a message; they left a line in the sand. What began as a quiet, heartfelt…

“SHUT UP, LEAVITT — YOU ARE TURNING YOURSELF INTO A CHEAP PERFORMANCE IN FRONT OF ALL OF AMERICA.”

They came for the ratings, but they left a wound in the country. It was supposed to be another primetime…

Jimmy Kimmel Blasts Trump at “No Kings” Protest: “Go to Hell!”

Late-night host Jimmy Kimmel made headlines on Saturday after delivering a fiery speech at the “No Kings” protest in Chicago…

Tunnel Was Sealed 120 Years Ago, What They Found Inside Will Shock You!

The mountains above Black Hollow do not rise so much as they accumulate—ridges upon ridges, like knuckles under a scarred…

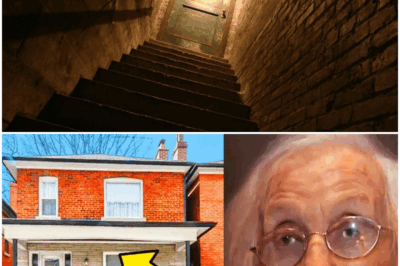

96-Yr-Old-Woman Sold Her Home & Warns Family Not To Open Basement. What They Find Inside Is Shocking

Under a gray Toronto sky that threatened rain, a ninety-six-year-old woman made a decision that would upend the quiet assumptions…

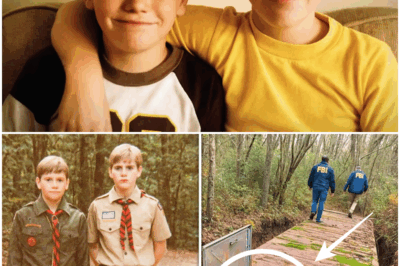

THE VANISHING: The Kinsley Brothers, the Storm, and the Bunker Beneath the Pines

The sky over Oak Haven State Forest went wrong before anyone named it. Sunlight dulled to a bruise; the wind…

End of content

No more pages to load