The mountains above Black Hollow do not rise so much as they accumulate—ridges upon ridges, like knuckles under a scarred glove. On winter mornings the air is thin enough to ring in your ears, and the light comes down in a pewter wash that makes everything—timber, scree, the pale runnels of frozen water—seem older than it is. It was into that light that a convoy of trucks crept along a single-lane dirt road, their tires grinding the frost-stiffened ruts until the sound carried up the slope like distant machinery remembered by the stone.

The men in those trucks were not there for folklore. They had a government contract and a schedule, portable compressors and core drills and a foreman who preferred facts to stories. His name was Mike Jensen. Thirty years in drilling and excavation had taught him to trust the plain languages—numbers, torque, the way a bit bites when you get your angle right.

He had read the file: an early twentieth-century tunnel in the Black Hollow district, sealed after a collapse and left alone for more than a century, now slated for environmental assessment and stabilization. The documents reached backward like a caution: unstable, unventilated, sealed indefinitely. They did not say haunted. The men in the trucks didn’t have to. These mountains have a way of teaching you humility, and the old-timers had a habit of lowering their voices when they mentioned Black Hollow, as if the stone itself were listening.

They parked in a clearing where the ground flattened into a work yard long since reclaimed by bunchgrass and wind. The tunnel mouth was visible even from the trucks, a pale oval of concrete set into the darker granite like a cataract. Iron bars, thick and badly rusted, crossed it in a pattern that felt less like engineering than intention. Somebody long ago had wanted it to stay shut.

“Looks solid,” said Travis, one of the younger hands, pinching the strap of his hard hat as if adjusting his sense of scale. Mike nodded and marked off distances on a clipboard. He told his crew what he always told them on a first day: take the time now; pay for it later if you don’t. They staged the rigs, checked the couplings, ran the compressors just long enough to hear the right pitch.

When the drill motors spooled up, the valley took on that particular vibration that moves through your bones before it reaches your ears. The first cuts bit into the concrete with a gratifying steadiness. Powder dusted their boots and then rose in slow scrolls across the face of the seal, coating the low shrubs in a chalky rime.

By dusk they had opened a hand-sized blister in the center of the slab, just enough to release a breath of air that felt like the exhale of a long illness—cold, metallic, stale. Even the men who didn’t believe in omens stepped back. Trapped air, Mike told them, though his own voice thinned as he said it. They tarped the gear and set a watch schedule, then built a small fire out of habit more than need.

The darkness comes quickly that high; the stars throw down a hard kind of light and the ridges turn into black teeth against the sky. Someone told a version of the story they’d all been warned about—the men of Black Hollow who went in and didn’t come out—and the others laughed the way crews laugh when they want the sound to fill a space that otherwise might be filled by thought.

Mike listened and did not correct the details. In the company records the episode had the bland gloss of liability: internal collapse, rescue impossible, shaft sealed to prevent further subsidence. He had been around enough boardrooms to recognize the phrasing. He had also stood at enough disaster sites to know that violence leaves a residue colder than fear.

They finished the cut on the third morning. The last section of concrete gave way with a deep, structural sigh and broke across the gravel in slabs that made the ground tremble when they hit. Dust came out in a wave that threw the men back and made them cough behind their respirators until the white cloud thinned and disappeared into the mountain air.

Behind it the tunnel yawned—black, slightly ovoid, edged with the fractured pale where the seal had been cut. Mike walked in first. His helmet light washed an anemic circle across the raw rock, catching in pockets of quartz, finding the old timber sets farther in. Nails had bled themselves into orange ghosts down the grain. Narrow rails still ran along the centerline of the floor, their iron scabbed with mineral bloom, half buried in drifted gravel. The air had that particular hush you only hear underground, the way sound moves close to the walls and stays there.

They found artifacts quickly. A pick head without its handle. A dented lantern frame. Leather that had remembered its shape long after it had forgotten its function. On one wall a line of charcoal slashes ticked out days or loads or wages—the counting of something that once mattered enough to mark against stone. The numbers stopped and started. Some trailed off diagonally as if the hand had slipped. The crew moved softly without realizing it, as if someone in the next room were sleeping.

They turned back when the air monitors began a slow, decisive drift into the yellow. Ventilation would have to be set; the old workings would not forgive hurry. At the mouth they stood blinking in the winter light and listened to the wind. Even the jokes sounded padded. By the fire that night no one told a story. The mountain had begun to tell its own.

On the fourth day they went deeper, the cold gathering along the floor, the smell of old metal and petrified wood thickening until the taste of rust sat permanent at the back of the tongue. The tunnel widened by degrees until the roof lifted and the walls drew back into a chamber large enough for a dozen men to stand and catch their breath all at once.

A fall blocked the far side, a long hump of stone and spoil that looked at first like any of a hundred ancient collapses. But there is a grammar to rock. You learn it or it kills you. Mike walked that pile slowly, his glove making half-moons in the dust as he brushed.

Natural cave-ins fracture and wedge; this had the interlocked regularity of intention. He found straight chisel marks on the shoulders of the larger blocks and mortar flecks where a seam should have been chaotic. He tapped with his knuckles and heard not the dull report of settled rubble but the muted hollowness of a wall built to fill a space.

“We’ll open a small sight hole,” he said, turning the way a man turns when he knows the decision is his to own. “No more.” His crew hesitated in that brief and ancient pause when caution conflicts with authority, and then Carter—a man old enough to have taught Mike how to read slate—brought the compact drill forward and set it where the stones met like teeth.

The bit chewed for minutes that stretched long. Dust fell in a steady whisper onto their shoulders. Somewhere in the roof a small pebble shifted and tumbled to the floor in a sound like a tap on glass. The first stone loosened without warning and slid out to hit the ground with a weight that reverberated in the cartilage of their knees. A breath of air came through the new gap that was colder than the tunnel behind them and carried a sourness that did not belong to age alone. Mike set his light and leaned in.

Beyond the wall there was a narrow chamber maybe a dozen feet deep and half that wide, with timber still holding its posture against the roof and the floor silted into soft drifts as fine as flour. The light made a slow sweep across the far side and caught a shape the mind registers before it names: pale arcs, the clean angles of joints, the empty gaze of a skull still cocked at the angle of its last living thought.

There were more—six, then seven—arranged not as if thrown but as if they had settled into one another the way cold settles into bone. Knees up. Arms folded. Some leaned against the wall as if bracing for an effort that never came. Between them lay the remains of purpose: a lantern collapsed into rust, a tin can with its lip peeled back, a notebook that had returned to its pulp except for the leather corners of its cover.

On the inner face of the wall, the one that would have been built last from the inside, the stones were cleanly tooled where a mason’s hand had found them. The truth assembled itself in Mike’s body before it resolved into words: this was not a barricade against falling rock. It was a sealing up. The men had built their own side smooth because they had understood what it was going to be.

He stepped into the chamber and the air wrapped him the way river water wraps you at the first plunge: absolute, unarguable. The silence down there was not the ordinary hush of underground. It had an edge to it—as if the last sound had been a long time coming and had not yet finished unspooling.

He set his light high and saw scratches cut into the stone near where the bodies leaned, the letters shallow and ragged and precise enough to be read across time. If you ever open this place, tell our families we waited. Farther along, more marks: initials, days tallied anew after the old counting had stopped, a date that had run out of room in the month and then stopped anyway. The ceiling above the huddle was scarred by short, hurried blows where a miner’s tool had struck and struck and then fallen away.

“Out,” Mike said, and heard in his own voice the tone the men around him had learned to obey. They did not argue. They passed the notebook from hand to hand, wrapped it in canvas, slid the loose stone back into place to keep the air from moving, and backed through the original tunnel to the light. On the surface a new kind of quiet met them, the quiet of a truth discovered and not yet spoken aloud. Mike called the county. He gave the facts and left out the rest because he had no language yet for the rest.

The investigation that followed had the procedural rhythm of any proper reckoning: seals placed, photographs taken, measurements logged, a meticulous removal of remains under the eye of forensic anthropologists who understood how to tell the difference between a fracture you get from falling rock and the delicate hunger of time. But even as the modern world set about doing its work with climate-controlled vans and zippered bags and respectful forms, another cadence started to surface, as if the mountain were turning itself inside out to show a second ledger.

Historians went to the archives in Helena and returned with the case files of the Black Hollow Mining Company: ink-brown ledgers, typed memos gone gray at the edges, correspondence in a hand that knew how to calculate the margin between loss and expense.

There it was: an internal collapse in Shaft 3, eight men trapped beyond a fall, surveyors estimating that a rescue drift would take two weeks if the slate held and the air could be managed. There, too, the decision: the board declaring the operation “financially unviable given current market conditions,” instructing the chief engineer to seal the shaft and “suspend all further action,” certifying the men “lost to accident.” Two signatures at the bottom made it a policy and a grave.

In a lab at the state university, the dead told the rest. Trace soot lined the inner crowns of the lantern chimneys. The fragments of wood on the floor matched saw cuts in the broken handles of picks—handles removed deliberately, as if by someone who feared those tools might be used against a wall intended to hold.

Bone marked by tiny transverse grooves testified to cramped, repetitive motion toward the end; hands had scraped at stone when steel was gone. Among the paper fragments conserved from the notebook’s leather were words visible under raking light when you learned how to look: we can hear them above us; day nine; rationed; it is quiet now. The dates on the scratches corresponded to a storm recorded in the region that winter and to a pay period ended without names in a ledger column that had previously always been filled.

By the time the story found the cameras, it had already become something heavier than a headline. The valley filled with the infrastructure of attention—satellite trucks, microphones with foam heads in the colors of far-away networks, producers standing with their backs to the mountain and their faces to the lens. Mike did not want that part. He was a foreman, not a spokesman.

But the county wanted a voice that had seen the chamber and could speak for it without embellishment. He took off his hard hat and held it against his thigh and told the facts. Eight men had been sealed alive a century earlier by order of their employer to protect a balance sheet. They had waited. They had left a message. They had built a wall from the inside because the other side had been taken from them.

“What do you believe happened in their last days?” a reporter asked, her eyes soft and her mouth already forming the follow-up. Mike did not answer the question she had asked. He answered the one that had been carried up out of the hole. “They asked us to tell their families,” he said, and felt the words move through his chest like a weight being set down. “So we are.”

The state did its own kind of work after that. It commissioned an inquiry into the old corporate practices, though everyone involved was long dead. It funded a memorial and then got out of the way when the local unions and the town historical society decided to place it where it belonged: at the mouth of the shaft, on a shoulder of rock that took the morning sun and threw a shadow across the valley at noon like a sundial.

The plaque was dark granite with the names etched deep enough to outlast weather, followed by the sentence carved from the wall: tell our families we waited. Families who suspected their ancestors’ stories ended in that mountain came to stand under the cold light and set their palms against the stone.

An old man cried the way a boy cries—sudden, clean, surprised by his own heart—as he traced initials that matched a brass tag in a box of his grandmother’s keepsakes. Someone left a miner’s lamp, rebuilt and polished, its fuel cup empty, its wick new and white.

When the formalities ended, the engineers did what engineers do best: they made sure the hole would not be tempted to open again. This time the sealing was slow and deliberate. They tied in the loose rock, took the load off the tired timber, poured the first layer of concrete and let it cure, then built up successive courses until the mountain’s static settled into a register that sounded like sleep rather than denial.

Mike stood with the crew for the last pour. He touched the wet surface with the side of his hand the way a mason will, not to leave a mark but to feel the truth of it. When the formwork came off and the face cured to a hard, solvent gray, he stayed a few minutes while the others stowed the last of the gear. He put his palm flat to the cured wall and said out loud what he had wanted to say since the moment he’d cut his light across those bones. “We came back.” It did not matter to him that he was late. The sentence had waited long enough.

In the weeks that followed, Black Hollow changed shape in the stories people told. The tales about hauntings and bad luck gave way to a narrative with dates and names, signed memos and forensic reports. Not less eerie—truth rarely is—but more exact. Schoolchildren came on field trips and learned to say “deliberate” and “policy” with the solemnity of kids who suddenly understand that decisions have bodies at the end of them.

The local paper ran a series on the mining camps and the men who built the county’s first schools with wages earned in places that could kill you for a cough. On the radio, an old fiddle tune from the period played between interviews with historians who explained what a “mortality clause” looked like in 1903 and why boards met in winter when the price of ore had fallen.

None of that changed what had happened under the mountain. It did, however, do something for the air above it. The valley wind, which had always moved with the practical business of weather, acquired a new undertone, a kind of undertow of remembrance that seemed to catch at your collarbone as you drove out at dusk. It was not supernatural.

It was the human fact of knowing what lay beneath your tires and choosing to carry that knowledge in a way that doesn’t look away. Some evenings—especially the clear ones when the light comes thin and long and you can see the dust of your own breath—you could stand at the memorial and hear only the air moving in the pines, and the silence would feel less like absence than accord.

For Mike, the work shifted but did not end. He sat for interviews he never wanted because accuracy matters when a story like this begins to travel. He met with the families who could claim a line to the eight and with the ones who felt, without documentation, that their grandfathers belonged to that dark archive of the sealed and the lost.

He answered questions about ventilation and rock competence and how you tell a deliberate wall from a heap of accident. He testified at a legislature hearing where men in suits who had grandfathered mines and cousins on boards asked, with what sounded like genuine bewilderment, how such a thing could have happened in the first place. He learned to stand the particular loneliness of telling a story for the people who cannot. It was not romance. It was work.

When he did return to the mountain, he preferred to go alone. He parked down at the lower gate and walked the road the way men walk a farm they do not own but have been asked to mind. He veered off where the pines thin and the stone comes into view and stood in front of the new wall. Granite plaque. Smooth concrete.

The outline of the old bars rusted away in their sockets and remembered only by the holes they had left. Above him the sky was the color of galvanized steel, a light he had learned to trust. He did not speak most visits. He didn’t need to. Sometimes, when a gust came down the draw, he imagined he could smell the old metal again, the tincture of history you cannot wash from things. It was not there, of course. The cavity had been sealed. What he smelled was winter coming. What he heard was the wind moving through a story that had finally been allowed to finish.

If there is meaning to be distilled from a place like Black Hollow, it lives in the practicalities as much as in the elegy. A century ago a group of men made an arithmetic of lives and dollars and chose the column that looked cleaner in a ledger. A hundred years later, a different group of men and women brought light, air, and accountability into the darkness that decision had created.

The mountain kept the record in its simplest form: bones, scratches, tool marks, a wall squared from the wrong side. It needed people to read it. The crew, the investigators, the archivists, the families, the children with their hands flat on the stone—together they made a book from a grave. The last line of that book is not the concrete poured or the camera crews sent home. It is the way the wind sounds once the story has been told properly: less like an accusation and more like an amen.

One evening in late spring, when the snow had run out of the gullies and the first wildflowers were trying the ground along the verge, Mike parked at the gate again and made the walk without thinking about his knees. He stood at the mouth and put his hand where he always put it, on the cool face of the seal. He thought about the men whose names he had said out loud in his kitchen the night they were carved on the plaque.

He thought, not for the first time, about the ones in other places who had not yet been found and the walls that had never received so honest a reading. He thought about lists and tallies in notebooks and on stone, and how you can count a day in cut marks or in the length of a note written under bad light. Behind him a truck downshifted far below and the sound climbed the slope like a slow wave.

When it faded the valley gave him back the quieter sound it had learned to make since the discovery—a kind of breathing. He let his hand rest on the concrete until it picked up the cold and then he took it away, the way you lift a palm from a forehead when the fever has finally broken.

The mountains of Montana will continue to loom, blue and gray and indifferent to the paper that fixes our names. The stone will keep what it keeps until someone with a drill and a conscience decides to listen. But at Black Hollow, something shifted.

The story that the company tried to write in a single sentence—financially unviable—has been replaced by a record of eight men who waited in darkness and left a message sharp enough to survive a century. The last thing Mike saw before he turned to go was the light washing across the plaque as the sun settled behind the ridge. It caught the carved letters and turned them briefly to silver. The wind rose and moved through the pines in a long, even breath that did not call for help and did not cry out. It sounded, to anyone willing to stand and hear it, like gratitude.

News

“SHUT UP, LEAVITT — YOU ARE TURNING YOURSELF INTO A CHEAP PERFORMANCE IN FRONT OF ALL OF AMERICA.”

They came for the ratings, but they left a wound in the country. It was supposed to be another primetime…

Jimmy Kimmel Blasts Trump at “No Kings” Protest: “Go to Hell!”

Late-night host Jimmy Kimmel made headlines on Saturday after delivering a fiery speech at the “No Kings” protest in Chicago…

They Vanished In The Woods, 5 Years Later Drone Spots Somthing Unbelievable….

At 7:45 p.m. on September 12, 2016, a Seattle rain tapped the windows of a one-bedroom walk-up while Mia Harlow…

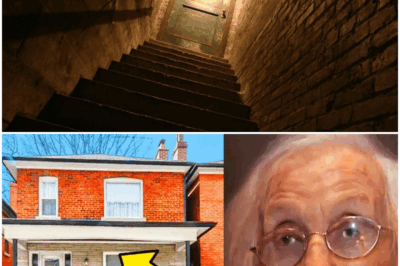

96-Yr-Old-Woman Sold Her Home & Warns Family Not To Open Basement. What They Find Inside Is Shocking

Under a gray Toronto sky that threatened rain, a ninety-six-year-old woman made a decision that would upend the quiet assumptions…

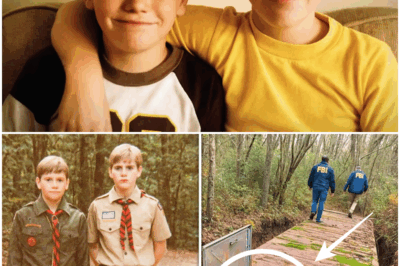

THE VANISHING: The Kinsley Brothers, the Storm, and the Bunker Beneath the Pines

The sky over Oak Haven State Forest went wrong before anyone named it. Sunlight dulled to a bruise; the wind…

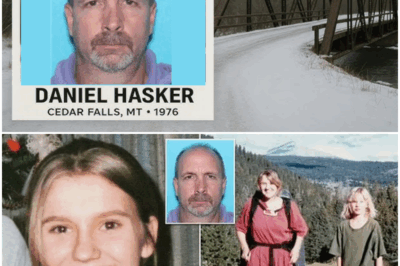

DNA FOUND – 1976 Montana Cold Case | Arrest Shocks Community

A warm lunch, a running engine, and a bridge that kept its secret for decades Under a low-grade December sky…

End of content

No more pages to load