On the morning of August 15, 2014, Glacier National Park woke to a cathedral hush: fog drifting like pale incense, streams whispering beneath bridges, the air cold enough to taste the metal of the mountains. At the Many Meadows campground, two rangers checked names in a spiral-bound logbook and slid bear warnings across a metal desk. A gray Subaru eased into a space by the trailhead and idled to a stop.

The driver’s door opened. A woman climbed out—slender, dark hair braided beneath a cap, camera slung across her shoulder. She signed her name with a neat hand.

“Traveling solo?” the younger ranger asked.

Clara smiled. “Mostly. I brought a camera so I don’t forget I was here.”

The older ranger, the one with the wind-burned cheeks, stamped the permit. “Weather looks fine,” he said, peering at the sullen cloud cling around the peaks. “Supposed to stay clear.”

Clara shouldered her pack and disappeared into a corridor of spruce. The road to Iceberg Lake snaked through tight turns of conifer, over slick boards, past cataracts that foamed like churned milk. She stopped often. The camera caught everything: a rivulet threading a stone, the white neck of a snow goat cresting a ridge, sunlight shattered on meltwater.

She reached the open plateau by noon, the goats grazing the snow’s margin like pale ghosts. A trio of retirees coming down recognized her later by the camera. She’d waved. She looked happy, one of them said. The kind of calm you only see on faces above tree line.

By three-thirty, the sky cinched like a pulled drawstring. The barometer in the valley plunged; a storm unzipped over the ridges with the rude suddenness of Montana weather. Snow came hard, knives instead of feathers, carving the air sideways. Wind climbed to forty miles an hour. Radios crackled in ranger cabins, but beyond the switchbacks their signals died in the ribbed stone. Up high, visibility dwindled to a dinner plate held at arm’s length.

At the campground, no one fretted. People came in late; hikers added bonus nights whenever a lake found them. Clara’s Subaru slept under a sheet of new snow. Inside, on the passenger seat, her notebook lay open: Day one, the weather is perfect. Tomorrow, through the tunnel.

That night, wind freighted the camps with a smell the old ranger couldn’t place. It was smoke mixed with something sweeter—paraffin and pollen, a beekeeper’s shop after a long day. He would remember that much. He would say it later, quiet, like an apology: The air smelled like cold wax.

She didn’t return on the seventeenth.

On the eighteenth, they launched the search.

They found the storm’s work everywhere: drifted cornices, rime clinging to the mouths of crevasses, a pass stitched shut by wind. A helicopter lifted from Columbia Falls and combed white ribs with a searchlight that lit only more white. On the north aspect near the tunnel, a dark fleck pinned itself to stone.

A team skirted the cliff and found it—the corner of a photograph, edges charred, image blistered by heat and cold. A snow goat, mid-step, in the exact posture Clara had captured at noon. Nothing else. Not a glove, not a strap, not a single bright shard from the world below.

By the fifth day, frostbitten volunteers wrapped their hands in duct tape and kept going, teeth clenched. The dogs lost her scent above the tunnel and milled, confused, then sat like someone had said stay. The handler wrote in his incident log: Trail goes to the mouth of Ptarmigan, then stops. Not lost. Stopped, like wind licked it away.

On September 12, they signed the document no one wanted to sign. Active search concluded. Probable hypothermia. Body unrecovered.

Her gray Subaru remained in its space for the winter like a gravestone no one had consented to erect. Snow buried it. Spring exhumed it with a shrug. The rangers started telling visitors, because they had to say something, “The owner didn’t come back.”

Her brother, Steven, quit his job in Seattle and came to sit with the map. Every evening he looked at the red grease-pencil sectors—the places they had walked and walked and found only quiet—and his mouth hardened into a line. “When a person disappears,” he said, “there must be a crumb.”

He hired a private investigator over the winter, a former Missoula cop named Harold Webb. Webb drove out when the roads were still laced with ice and climbed until the park showed him its unkindest angles. He came back with only a sketchbook of ravines and a theory he didn’t share with the sheriff: the storm might have pushed Clara into the burr of old caves at the foot of Mount Sier—an area locals called Sister in the lazy way names blur when they live too long in mouths.

There was no way to check until things melted.

Time, with its sandpaper patience, wore ten years off the case. The county’s file yellowed. The Subaru finally left the trailhead. Her name flickered, now and then, on message boards where strangers trade solace for superstition. In one thread a woman said she’d seen Clara in Utah. In another, a man posted a photograph of a bluff and claimed the clouds spelled come home.

No one ever made good on those sightings.

Glacier held its breath and went on making winter.

On July 12, 2024, three members of Geoclimate North, a research team with the patched-together budgets of noble causes, hiked to the northeast shoulder of Mount Sier. The decade’s hottest summer loosened the ancient grip of the ice. Drones had mapped a new depression in the glacier the day before: a circular seam with the shine of water at the bottom.

The team lead, Mark Reynolds, had the clipped poise of someone who’s been told to go first most of his life. He was a former military climber with a knee that sang when rain came through. Rebecca Stone, a graduate student from Helena, wrote everything down and loved the mountain like a complicated aunt; she kept a journal in a plastic bag and reread it at night like scripture. The third, Noah Woods, handled rigging and cussed in a gentle way that made the others laugh.

By late morning, the three stood at the lip of a slanting shaft. It plunged at a forty-five-degree angle into blue—clear blue, glass blue, the kind of blue the ocean wants when it dreams of being harder. Water dripped far below, a patient metronome. The air rising from the shaft smelled clean and faintly sweet, as if bees had threaded some invisible path there long before people bothered with names.

“Depth?” Mark asked.

“Twenty yards, give or take,” Noah said, looping rope through a steel pin he pounded into a seam of rock. “I’ll anchor for you.”

Mark descended first. The rope hissed through his gloved hand. Light bled out of the world in a slow fade; the ice swallowed it whole and turned it into something else. The walls were so clear in places that voids beyond them looked like rooms. When his crampons hit permafrost, sound changed. The shaft opened into a gut of a cavern—an oculus above, a domed hall below.

“Cave,” he called. “Big one.”

Rebecca followed, then Noah. Their headlamps braided white bands across the walls. The floor crunched with pebbled ice. In the center, meltwater braided itself into a rivulet and pooled in a shallow dish in the rock. The air was still, dense, holding a sweet tang that made Rebecca’s throat tighten. “Like wax,” she murmured, not understanding why the word fit and could not be unchosen.

They stepped past ice spurs. The cavern widened and then stopped as if it had been designed, proportioned, intended—a circle of stone at its heart, a dais the exact height of a prayerful hand.

On it lay a body.

She looked at first like one of those treasures coaxed from bogs—the soft, exact face of someone dead a thousand years. But this woman’s skin was pale and taut, stretched gently over the hinge of cheekbones. Her hair—dark, tangled—fanned in a line toward one shoulder as if wind had once gone through and was frightened away. Her arms were folded across her chest, fingers cupped like a supplicant’s. A sheen covered her, glossy, golden in their lights. Wax. Not poured thick like candle drippings, not sloppy. Layered. Deliberate. Reverent.

A cord circled her neck. A small feather lay in the hollow where collarbones meet.

Rebecca felt certain—instantly, viscerally—that the cavern did not belong to the present tense. Some human hands had promised this space a long vigil. “This is not… natural,” she said, voice small against the curved roof. “This is a ritual.”

On the altar, to the right of the woman’s hands, rested wooden figures carved with an ignorance that looked like devotion—goats with too many horns, people whose legs tapered to stalks. Flat stones were incised with spirals and wave marks, a geometry that suggested tides in rock. A black glyph—circle bisected by a cross—smoked the wall, as if sketched with soot.

Mark stood very still, everything in him refusing to move too quickly. He leaned in. The face was peaceful, yes. The lips slightly parted, as if about to form a word. The wax was matte until breath warmed it and then it caught light as if from inside.

“Could it be a fake?” Rebecca asked, the question thin with hope and fear both.

Mark shook his head. “No.”

He didn’t say, No, because the hair at the base of her braid is slightly oily, as if it remembers human skin, and because the wax holds a scent that isn’t factory, that is bees and wildflowers in a place bees can’t reach, and because if I lay my thermometer on her, the number will be wrong for stone.

Noah went up to call it in. His boots thudded up the line. Their radios snapped and hissed, coughed a connection, and then held. When the thump of blades finally shook snow from the mouth of the shaft two hours later, Rebecca had written everything down twice: woman, wax, figurines, symbol, smell honey/smoke, silence like a mouth that refuses to close.

The rescue team lowered a sealed capsule. Even men who had hauled bodies off cliffs and out of snowfields fell quiet. One of them, an old hand with a bad shoulder, crossed himself.

They carried the woman like all of this had to be true.

Helena’s forensic lab hummed through the night.

They worked in bite-sized meticulousness, as if any rush might break some unspoken truce. The wax scraped in thin, amber curls that smelled faintly of summer. Under microscopes, technicians found pollen granules clinging to the wax—small grains with spiky coronas, unlike any plant cataloged in Montana’s present day. Propolis glinted; the bees had sealed this shroud as carefully as the hands that placed it.

The dental chart matched a missing person’s file before midnight.

At 2:07 a.m., DNA confirmed what the room had already started to know with a low ache: the woman was Clara Mitchell.

Dr. Henry Quinn, a forensic pathologist given to silence and accuracy, wrote without flourish. He noted what he saw, what he did not see. There were no fractures, no bruises, no sharp-force injuries. Internal tissues were preserved to a degree he had not seen outside of freezers and fables. The heart showed signs of a prolonged struggle against the cold. Likely hypothermia, he typed. Cardiac arrest.

But the marvel—that troubling marvel—was the preservation. The wax had sealed the body against bacteria and air, but it had done more than that. It had slicked into pores and yet left the skin pristine. No bloating. No discoloration. No smell of decay. Quinn pressed a finger to the woman’s wrist and thought, absurdly, that warmth should rise to meet him like a shy bird.

When they uncurled her fingers, they found an object pressed into her palm so tightly the wax held its shape around it. They teased it out slowly, melting the shroud with controlled heat. A pendant—an amulet carved from the horn of a mountain goat—lay in their tray. The surface had been polished to a milky shine by more than time. Along its edges ran symbols—triangles, spirals, wavelets, and, over and over, a triangle with an eye in the center.

“Local?” an anthropologist asked in the morning, after coffee, bent over the tray.

“No.” Another shook her head. “Not to my knowledge. The technique’s odd. The material’s ours. The hand is not.”

Quinn made a private note where no one else would read it: Wax applied postmortem. No trauma. No toxins. No sedatives. Someone loved the dead enough to keep them.

Reporters gathered faster than the lab could pour coffee. The sheriff’s spokesman stood at a lectern and cleared his throat and said phrases that smelled as if they had been taken out of storage and aired for the first time in a decade: unique case… cooperating agencies… no evidence of foul play… next of kin notified. No one asked about the smell of wax. No one thought to ask how reverence might look if you’d never met it before.

Steven was flown in. He stared through a glass wall at the girl who used to beat him to the mailbox and tear open catalogs to look at the trees. He had not cried in ten years and did not cry then. “Thank you,” he said to no one and everyone. “Thank you for finding her.”

That night, Rebecca lay awake in her motel and tried to smell the cavern again. She had imagined caves as dead throats. This one had been different—like someone had lit a hundred candles long ago and the stone still remembered the heat.

The FBI arrived with their quiet briefcases and busy notebooks and, as they always do, all the names for things. Special Agent Jonathan Hail had made a career from mapping the border where faith, wilderness, and human need rub each other bloody. He flew in from Denver with the tired grace of a man who sleeps on planes and woke the next morning with Glacier in his bones like a fever.

He went to the cave and stayed there for two hours. He photographed the altar. He photographed the soot glyphs and the spiral stones and the wrong little statues. He knelt and touched a drip of wax on the floor with his knuckle and rubbed it against his thumbnail. He leaned close to the wall and smelled for smoke.

Back in the temporary command trailer, he asked for every missing-person report in a fifty-mile radius for the last fifty years.

Patterns came up like bruises. Seven disappearances inside a rough circle of the mountain’s shoulder. Mostly women. Mostly solo hikers. Summer storms. No bodies. No gear found. Search dogs that went quiet at gullies like they were standing at a door.

He talked to old men with weathered hands in cafes where the coffee is cheap and the sugar pours like sand. At St. Mary’s, a shepherd named Milton Drake stirred sweetener into his cup with a patience that made Hail ache. “You’re asking about them,” Milton said, not a question. “The ones we call the silent.”

“Who are they?”

Milton stared at the sugar granules dissolving and said, “You can’t see them. That’s almost the point. They’ve been here longer than some of our fences. They keep to themselves. They do no harm unless you try to make them speak.”

Two hunters from Kalispell told him about a camp they’d stumbled upon in a high valley. No gunmetal. No propane. People with banded heads and bare feet who lifted their palms in greeting and then, with slow kindness, asked them not to come back.

Guardians, one had said. That’s the word they used. Guardians.

Hail dug into the forest-service archive, the one with dust, not databases. He found a reference to a schismatic sect that had sloughed themselves into the mountains around 1909—a community called the Order of Silence. Their leader, a preacher named Elias Gray, had brought twenty men and women upriver and built cabins with patient hands and taught them a theology as stripped as their lives: stone is a spirit; storms are that spirit’s hand; the only gift accepted by stone is stillness.

They believed—so much the documents made clear—that weather can be negotiated with acts of reverence. A life laid down voluntarily anchors a season. Candles lit in caves quiet the wind. The names of the old Blackfeet rites appear in Gray’s copied sermons like footprints he had tried not to press too deeply. The Order left the records in the thirties with a note—we go where paper does not—and then, as far as the government was concerned, dissolved into myth.

Hail hiked to the valley north of Bellingham Creek with a tribal elder who knew how to move on stone like a man carrying water in both hands. They found a circle of toppled foundations draped with moss. On a slab in the center, a triangle with an eye had been cut deep enough to survive a century of weather.

That night Hail wrote in his journal, a habit he never broke: They believe balance is a geometry you can keep with silence. They do not take life, they frame it.

There was nothing to charge. There was only a woman dead in winter and preserved against rot by a shape of love the world had forgotten how to recognize.

But satellite images are implacable. One of Hail’s analysts noticed faint heat signatures in a remote valley between the Sier ridges and the Bellingham drainage—fireflies of warmth where no maps drew roads. Hail chose horses over blades. He smelled the valley before he saw it: the green sweetness of spruce, the clean bite of water, the smoke of wood cut with hand tools, not gas.

They came at dawn.

The settlement looked exactly like the word settlement promises and never delivers: huts roofed in moss, smoke curling from holes, a circle of stones with char still charcoal dark. There were eleven people. Bare feet that had hardened into shoes. Linen shirts belted with rope. Heads banded with cloth that kept hair out of eyes. They did not pick up tools as weapons. They did not run. An old woman in a white mantle walked to the forefront and lifted her hands in greeting.

“We knew you would come,” she said, her voice thin as streamwater. The younger woman who stood beside her translated with a cadence that made the English sound softened, made, remade.

In a hut that smelled of wax and herbs, Hail found a leather-bound book with a broken strap. Inside, in a tidy hand, ran Clara’s words—shorter toward the end, as if cold had made her letters blunt. Snow in August. Lost the trail. If I sleep here, so be it. The wind sounds like it’s breathing in time with me. I am not afraid.

“What did you do?” Hail asked the elder later, the hut grown too small for the ache in his throat. “When you found her.”

“We did not touch her life,” the woman—Mirren—said. “You must say this when you speak of us: we found her after she went still. We saw the quiet in her eyes. We knew the storm had accepted her. We knew we must keep her shape, to hold its peace.”

“What does that mean?”

Mirren put her hands together, not in prayer—something older, something like debt. “We keep vigil. Our mothers kept it. Their mothers kept it when the government said they did not exist. There are storms you cannot negotiate with words. There is a geography to calm. The wax is not death. It is honoring. She was not ours to burn in the sun.”

The amulet’s origin, then, was unsurprising. A goat’s horn, shaped by quiet hands, symbols cut with a nail and patience, triangles with eyes, spirals like wind on water. The same glyph Hail had seen carved into old stone. The same eye held in Clara’s palm.

They let the agents take blood pressures and temperatures. They let nurses look into their mouths with penlights. When Hail told them they had to come down for a while, they did not argue, though they sagged with a grief that had nothing to do with fear. The youngest woman pressed her palm to a tree on the edge of the clearing. One of the men knelt to tie a strip of cloth around a sapling the way a mother braids a ribbon into a child’s hair.

As they left, the valley seemed to breathe—an exhale from pine and rock, a loosening because there were witnesses now.

At the press conference, the words were careful. No evidence of homicide. Natural causes. Ritual handling postmortem. The internet rushed to have stronger opinions. Cult kidnaps hiker, preserves her like wax saint. Ancient tribe honors stranger with vigil. National parks are full of secrets. In the space between those sentences, the truth grew feral.

Steven flew home with a small cardboard box of items the agents had taken from the cave and cleaned: a ring he recognized, a scrap of notebook, the amulet. He did not know what to do with it and put it on his kitchen table beside the mail. At night he touched it, then jerked his hand back because it felt alive, warm enough to startle.

Agent Hail wrote his final report and signed it and then wrote a second, the one no one would read but him: They are not killers. They are keepers. What we call disappearance, they call service. We use words like ‘closure’ because paper needs an ending. The mountain has never understood our verbs.

Summer worked itself out. Fall came with its shrewd thin light. The first Sunday after the case closed, a ranger walked to the sign at the old trail and found four words scrawled at the bottom in a careful hand: The forest remembers everything.

Reporters called it vandalism. The ranger did not scrub it off.

The cave was resealed. The valley emptied of its quiet people, perhaps temporary, perhaps not. There was talk of resettlement assistance. There were meetings with legal pads where someone had drawn a triangle with an eye in the corner without meaning to. Rebecca went back to the lab and then, because the lab lights were no fit for someone who had seen long blue, she quit her graduate program.

She moved to a town with a single blinking traffic light and waited tables and wrote in her journal in the late afternoons when the café went still. When snow fell, she drove to Glacier and parked in the lot where the Subaru had once slept and sat until her hands went numb. Sometimes she thought she could smell wax when the wind shifted, the way your mind can invent the sea if you listen long enough to a highway.

Steven took Clara’s ashes to a small park near the water in Seattle and poured them where she had once said she would like to plant something that climbed. He spoke to her. He did not say goodbye because the word always felt like throwing a coin in a well that will keep it.

Hail returned to Denver. He took very long showers until the cave air left his hair. In the evenings, with a whiskey he did not drink, he thought about the problem of mercy. How many ways there were to hold a body. The ways the world names them: sacred; profane; felony; grief. He wrote a letter he did not send to the old woman—Mirren—telling her he understood the edge of her language, if not the center.

Occasionally, hikers claim—even now—that at twilight on the northeast shoulder of Sier they hear a humming, low and sustained, like someone singing the note that holds quiet together. Photographs taken at dusk warp with an odd flare: a gold haze, like breath on glass. Rangers find circles of candle wax in shallow caves, wicks pinched in neat spirals, no footprints leading in or out. You could build your own faith out of those details, if faith is something you make to lower your heartbeat enough to sleep.

There is a photograph you can still find if you know where to look, posted by someone who did not know what they held. It shows a slab of old stone, moss like velvet, a triangle with an eye cut into its face. The caption is a joke about aliens. In the first comment, someone writes, It’s not an eye. It’s a way to say ‘we saw.’

When the county finally updated the file, the case name shifted from Missing to Closed. Bureaucracy demands that boxes be checked. The final line read: Death by exposure. No third-party involvement. Postmortem ritual preservation. It is not false. It is only smaller than what happened.

If you go to Glacier and let the trail take you up until you feel the blood in your gums and the muscles across your shoulders begin to complain, you can stand at the lip of a world that tried to keep a secret for ten years and almost succeeded. Close your eyes. Hear the wind pull itself thin between rocks. Smell, if you can, that faint sweetness under snow.

Imagine a woman stepping off the trail not because she was foolish, but because the mountain asked and she answered. Imagine hands—strange, gentle—finding her when the storm emptied itself and carrying her someplace stone could remember her.

Imagine that something in the world that is not a person and is also not not a person accepted the gift and released its anger for a season.

We tell ourselves stories to keep from falling into the cracks between what can be known and what is only felt. Some stories hold. This one holds like wax: warm for a breath, then hard as amber, with something soft trapped forever inside.

In a drawer in Hail’s desk there is a photocopy of the amulet. The triangle, the eye, the spirals. On some nights he takes it out and lays it on the desk and does nothing, because some reverence is best performed with your hands still.

On her kitchen table, under a globe of dusty light, Rebecca keeps a candle. She never lights it. She only touches the wick with the tip of her finger, as if making sure that, if called upon, she’d remember how.

And on a morning in August, years after, a boy hiking with his mother asks why the plaque by the trail says In Honor of Clara Mitchell when there is no grave. His mother kneels to tie his boot and says, “Because sometimes we bury the map and keep the place.”

Above them, the mountain breathes ice and weather and a kind of old attention.

Somewhere under that, deeper than a decade and closer than a hand, the stone altar keeps its shape. If you could go there—and you cannot—and if you could stand in that circle of cold and lay your palm on the slick rock, you might feel it: the faint, impossible warmth of a body kept, not because the world needed a relic, but because a small order of silent people believed they could teach the wind to be gentler if they held, and held, and did not let rot take what the storm had been given.

This is not a story about a woman who vanished.

It is a story about the ways a place can keep you, even after you stop needing it.

And how, when the glacier finally opens its mouth and speaks, what spills out is not horror, but a grammar of care we don’t have words for anymore.

News

Couple Vanished In Oregon – 6 Years Later THIS Was Found Inside An Abandoned Tree Cabin…

THE TREE THAT STOOD WATCHING — The Vanishing of Alex and Sophia Marlo In August 2012, the Marlos set out…

At Diane Keaton’s FUNERAL, Al Pacino Revealed A HORRIFYING Story That Left The World HEARTBROKEN.

On October 11, 2025, a soft hush settled over Hollywood. Diane Keaton—ever luminous in a wide-brimmed hat and a wise,…

They Vanished in Redwoods, 4 Years Later Hikers Find a Strange Fungus Infestation at Tree…

The last photo uploaded to the cloud looked like a postcard you’d buy at a ranger station. A wide ribbon…

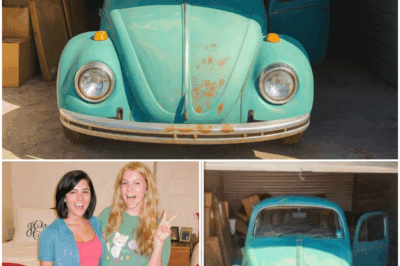

College Student Vanished in 1995 – 11 Years Later Her Car Appears in a Storage Auction…

The metal door screamed as it rolled up, a rusted shriek cutting across the auctioneer’s chant and the white breath…

Before Death, Diane Keaton Finally Opens Up About Her 2 WILD Children…The Shocking Truth

THE LAST CONVERSATION: A MOTHER, A CHILD, AND THE SKY The door clicked softly behind the doctor — a polite…

The Last Hug: A Mother, a Boy Named Léo, and the Promise of the Sky

It was a quiet morning when the doctor closed the door behind him. The click was soft — polite, almost…

End of content

No more pages to load