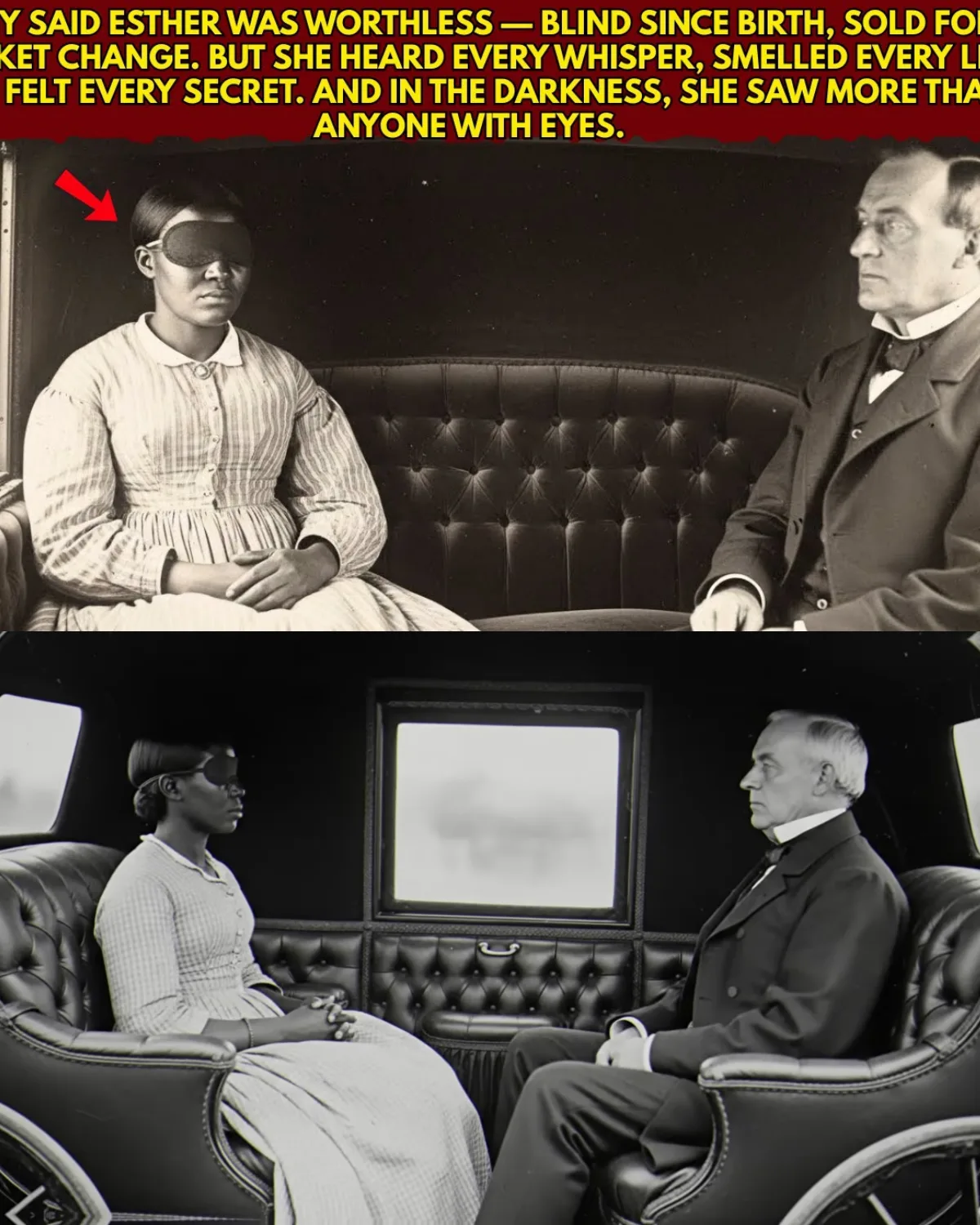

Bought for 25 Cents: How a Blind Enslaved Woman Sent a Charleston Aristocrat to the Gallows in 1852

On a suffocating May morning in 1852, at a slave auction in Charleston, the crowd barely noticed her.

She stood on the edge of the auction block with the others no one wanted—the elderly, the sick, the disabled. At thirty years old, blind since birth, she was labeled defective property. The auctioneer’s voice dripped with contempt as he described her.

“Blind female. Can perform simple kitchen tasks. Completely docile.”

The bidding stalled.

One dollar. Silence.

Fifty cents. No response.

Twenty-five cents.

That was her worth.

When Josiah Caldwell raised his hand, he wasn’t buying labor or skill. He was buying what he believed was harmlessness—a blind woman who couldn’t see, couldn’t know, and couldn’t testify.

Her name was Esther.

And within a year, she would destroy him.

Born Blind, Branded Worthless

Esther was born in 1822 on a plantation in North Carolina. When the midwife realized the infant could not see, the plantation owner ordered her drowned. Esther lived only because her mother begged for mercy and promised her blind child would never be a burden.

From the beginning, Esther learned survival meant adaptation.

Without sight, her other senses sharpened beyond anything her enslavers imagined. She learned to recognize people by the sound of their footsteps, by the rhythm of their breathing. She could identify fabrics, tools, and objects by touch alone. She smelled sickness before symptoms appeared—and fear before words were spoken.

Most importantly, she learned to stay quiet.

In a world where enslaved people were punished for intelligence, Esther hid her abilities behind the mask of helplessness.

Sold and Forgotten—Until Charleston

After years of being resold as “damaged goods,” Esther’s price dropped lower and lower until she arrived at the Charleston auction worth less than a meal.

Josiah Caldwell, a wealthy merchant with a pristine reputation, bought her on impulse. He owned a grand house on Meeting Street, attended church faithfully, and moved easily among Charleston’s elite.

No one suspected what he truly was.

Esther was assigned to the kitchen, peeling vegetables in a corner, ignored by most. But while her hands worked, her senses cataloged everything.

And then she smelled it.

The Poison No One Else Noticed

One afternoon, Caldwell passed through the kitchen carrying his wife’s meal tray.

Mixed with the beef broth was a faint but unmistakable scent: bitter almonds.

Arsenic.

Esther froze. She had smelled it before, years earlier, when rat poison was used on a plantation. The smell was faint, but her nose never forgot.

Over the following weeks, she detected the poison again and again—never daily, always spaced apart. Slow. Deliberate. Designed to look like illness.

Caldwell was poisoning his wife.

Doctors diagnosed a wasting disease. Charleston society offered condolences. Caldwell played the grieving husband perfectly.

But Esther smelled the truth.

A Crime Hidden in Plain Sight

As months passed, Esther noticed more.

Caldwell’s footsteps changed when he carried poisoned meals—slower, careful, deliberate. His breathing quickened when doctors asked questions. His sweat smelled different when he lied.

She also heard the rest.

Financial fraud. Bribery. Forged documents. And the quiet cries of enslaved women summoned to his study after dark.

By the time Mrs. Caldwell died in August 1852, Esther knew she had witnessed a murder no one else could prove.

And she knew she would likely die if she spoke.

The One Man Who Asked

Six weeks after the funeral, Catherine Caldwell’s brother arrived in Charleston. Unlike others, he had doubts. His sister’s illness hadn’t felt right.

He asked to speak privately with the household slaves.

When he sat with Esther, he assumed she had seen nothing.

Instead, she told him everything.

“I smelled the arsenic,” she said. “I heard the lies. I know what happened.”

For the first time, someone listened.

A Courtroom That Held Its Breath

Slaves were not allowed to testify against white people—certainly not blind slaves. But Catherine’s brother hired a daring lawyer who believed Esther’s senses could be proven.

In November 1852, Charleston’s courthouse overflowed as Esther was tested publicly.

She identified strangers by footsteps alone.

Described people from the scent of their clothing.

Recognized objects by touch with surgical precision.

Detected lies by changes in breath, voice, and sweat.

The courtroom fell silent.

The judge, stunned, made history.

Esther would testify.

The Trial That Shattered a Reputation

In December 1852, Esther took the stand.

She described the poison. The pattern. The smells. The sounds. The deception.

Caldwell’s attorney attacked relentlessly—but Esther never wavered.

After days of testimony and deliberation, the jury returned its verdict.

Guilty of murder.

Josiah Caldwell was sentenced to death and hanged in February 1853.

Freedom and Legacy

Esther was freed by court order.

She left Charleston for Philadelphia, where she became a teacher for blind children, married, raised a family, and lived out her life in freedom.

She died in 1891, buried under her own name.

Once worth 25 cents.

Priceless in history.

News

America Copied Germany’s Deadliest Machine Gun — Then Forgot a Quarter-Inch That Made It Actually Work

America Copied Germany’s Deadliest Machine Gun — Then Forgot a Quarter-Inch That Made It Actually Work Part 1: One Shot….

America Rushed a “Tank Killer” Into Battle — and Handed Young Soldiers a Metal Tube That Wouldn’t Even Fire

America Rushed a “Tank Killer” Into Battle — and Handed Young Soldiers a Metal Tube That Wouldn’t Even Fire Part…

They Said the Sherman Was Finished in 1945—So Why Did It Keep Fighting for 73 More Years Across Deserts, Jungles, and Frozen Borders?

They Said the Sherman Was Finished in 1945—So Why Did It Keep Fighting for 73 More Years Across Deserts, Jungles,…

They Thought America Was Soft—Until Fire Fell From the Sky: How Japan Misread the United States, Ignored Its Sharpest Admiral, and Paid the Price in Ash and Iron

They Thought America Was Soft—Until Fire Fell From the Sky: How Japan Misread the United States, Ignored Its Sharpest Admiral,…

The $100 German Machine Gun That Ripped the Sky in Half—How a Lantern Factory’s Stamped-Steel Gamble Rewrote Infantry Warfare

The $100 German Machine Gun That Ripped the Sky in Half—How a Lantern Factory’s Stamped-Steel Gamble Rewrote Infantry Warfare and…

They Bought America’s “Failed” Airliner in Crates, Faked Its Death in Tokyo Bay, and Tried to Turn It Into a Pacific Super-Weapon—How Japan’s $950,000 Gamble

They Bought America’s “Failed” Airliner in Crates, Faked Its Death in Tokyo Bay, and Tried to Turn It Into a…

End of content

No more pages to load