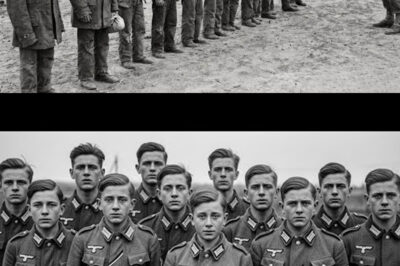

In the aftermath of World War II, the world was left grappling with the consequences of a conflict that had claimed millions of lives and left entire nations in ruins. Among the many stories that emerged during this tumultuous period was that of a group of German child soldiers who found themselves in an American prisoner-of-war camp in Oklahoma. Captured at a young age, these boys, some as young as fourteen, had been thrust into a war they did not fully understand, and now, as the war had ended, they faced an uncertain future.

Hans, a fifteen-year-old boy who had been captured on the Western Front, sat in Barracks 7 of Camp Gruber, Oklahoma. He had spent eight months in the camp, where he experienced kindness, safety, and a sense of normalcy that had been absent during the war. The camp director, Colonel James Patterson, informed the boys that the repatriation process had begun, and they would soon be sent back to Germany. For most, this news was met with relief and anticipation of reuniting with family. However, for Hans and his fellow child soldiers, the prospect of returning home was filled with dread.

As Patterson delivered the news, Hans stood up and spoke in broken English, expressing the heart-wrenching reality of their situation: “We have no home.” His words resonated deeply with the other boys. Many had lost their families and homes during the war, and the thought of returning to a devastated country filled with rubble and starvation was unbearable. Friedrich, another boy in the barracks, echoed Hans’s sentiment, stating, “America give us chance. Germany give us gun and say ‘die.’ I choose America.” Their plea to stay in America was met with the harsh reality of American law, which mandated that all POWs must be repatriated, regardless of their age or circumstances.

Colonel Patterson was troubled by the boys’ situation. He recognized that these were not hardened soldiers but children who had been forced into a conflict. That night, he discussed the matter with his wife, Martha, who volunteered at the camp. She questioned the fairness of sending orphaned children back to a country where they had lost everything. This conversation ignited a spark of hope in Patterson, who began making calls to the War Department and immigration officials, seeking a way to help the boys.

Despite their efforts, the responses were consistent: there could be no exceptions to the repatriation law. However, the boys were not ready to give up. They had formed bonds with the local community, particularly with families who had taken an interest in their well-being. One such family was the Hendersons, who had welcomed Hans into their home. Mrs. Henderson, who treated him like another son, was devastated when she learned he would be sent back to Germany. She began a petition in Muskogee, gathering signatures from townspeople who supported the boys’ desire to stay. Within weeks, she had collected 847 signatures, demonstrating the community’s compassion for these orphaned children.

As the story gained traction, local lawyer Robert Chen stepped in, offering to take the case pro bono. He recognized that these boys were victims of circumstances beyond their control and argued that repatriating them to a devastated country was cruel. Despite the legal challenges, the community rallied around the boys, with families stepping forward to sponsor them, offering homes and support.

However, federal immigration law had no provisions for enemy orphans, and the system struggled to accommodate the unique situation. As the transport date approached, the boys were loaded onto trucks bound for repatriation, with Mrs. Henderson standing at the fence, crying as she watched Hans look back at her through the window. Many believed this was the end of their story, but they were wrong.

While some boys returned to Germany, others managed to stay connected to their American sponsors through letters and care packages. Hans, Friedrich, and a few others disappeared from the official repatriation records, leading to speculation about their fate. In 1952, a young man named Hans Keller became a naturalized American citizen in Oklahoma, sponsored by the Henderson family. His official story claimed he had come to America as a displaced person, a war orphan who had spent years in refugee camps.

Hans lived in Muskogee until his death in 2003, becoming a teacher and raising a family. Every year on VE Day, he visited Colonel Patterson’s grave, honoring the man who had tried to help him stay in America. Hans’s story serves as a powerful reminder of the impact of compassion and humanity in the face of rigid laws and systems. It highlights the importance of seeing beyond labels and recognizing the shared humanity in others, especially in times of conflict.

The lesson of Hans’s journey isn’t just about the complexities of immigration law; it’s about what happens when ordinary people choose to lean toward justice. The Oklahoma families didn’t see “enemy soldiers.” They saw children who had been handed rifles instead of textbooks. Their willingness to advocate for these boys changed lives and created a legacy of compassion that transcended borders, reminding us that sometimes, humanity triumphs over bureaucracy.

News

How American Soldiers Chose to Show Kindness by Bringing Hamburgers to German Child Soldiers Facing Execution in the Aftermath of World War II, Transforming a Moment of Fear into an Unforgettable Act of Humanity and Understanding.”

A Hamburger of Hope: The Story of Mercy in the Face of War In April 1945, as World War II…

“Understanding Eisenhower’s Strategic Decision to Halt Patton at the Elbe River: The Controversial Order That Allowed Stalin’s Forces to Capture Berlin and Shaped the Post-War European Landscape, Highlighting the Complex Interplay of Military Strategy, Political Calculations, and the Need for Allied Unity in the Final Stages of World War II.”

The Decision to Halt: Eisenhower, Patton, and the Elbe River In April 1945, as World War II neared its conclusion…

How an American Soldier’s Compassion for a Starving German Mother and Her Children During Post-War Europe Transformed Their Lives and Highlighted the Power of Humanity Amidst the Devastation of World War II.”

A Simple Act of Kindness: The Lasting Impact of One American Soldier’s Generosity in Post-War Berlin In March 1946, Berlin…

“Unraveling the Mysterious Escape of German General Hans von Falkenhausen: The Discovery of His Disguise and Official Papers Generations Later in Forgotten Archives, Shedding Light on His Daring Efforts to Evade Capture at the End of World War II and the Broader Implications for Post-War Justice and Accountability in a Chaotic Europe Struggling to Rebuild After the Devastation of Conflict.”

The Hidden Legacy: Anna Mueller’s Discovery of a Nazi General’s Secret Life In the summer of 2019, Anna Mueller inherited…

“Exploring the Intricacies of Mathematical Formula Formatting: Essential Guidelines for Presenting Complex Equations in a Clear and Structured Manner to Enhance Understanding and Avoid Common Rendering Issues in Various Contexts, While Emphasizing the Importance of Using Block Format for All Mathematical Expressions to Ensure Clarity and Consistency in Communication, and Highlighting the Critical Rules for Effective Presentation Without the Use of Tables, Thus Enabling Readers to Grasp Mathematical Concepts More Effectively and Facilitating Better Engagement with the Material Through Proper Formatting Techniques.”

The Crucial Role of General Patton in the Normandy Campaign: A Turning Point in D-Day Operations The Normandy invasion, known…

“The Forgotten Story of German Child Soldiers in Oklahoma: How Young Boys Refused to Leave America After World War II, Navigating Identity, Trauma, and the Complexities of Belonging in a Foreign Land”

The Journey of Hans Keller: A German Child Soldier’s Story in Oklahoma In the chaotic aftermath of World War II,…

End of content

No more pages to load