Why German Commanders Couldn’t Believe Patton Was Stopped

On September 5th, 1944, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt returned to his former headquarters in the West for the first time in two months. The last time he had been there, he had delivered a grim assessment to Hitler’s staff, declaring that the situation in Normandy was hopeless and that Germany should seek peace. For his candor, he had been dismissed. However, the dire circumstances of the war had compelled the German high command to call him back, a clear indication of how desperate their situation had become.

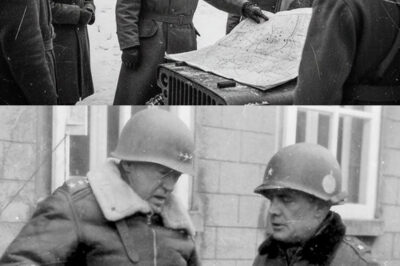

Awaiting von Rundstedt was General Günther Blumentritt, the chief of staff for all German forces in the West, who had laid out maps across the table. There was no need for speeches; the maps told the story. The Allied breakout from Normandy, known as Operation Cobra, had taken place six weeks earlier, and since then, American and British forces had surged across France at an unprecedented pace. By early September, most of France was in Allied hands, and Anglo-American spearheads were rapidly approaching the German border.

Blumentritt pointed to the southern sector of the map, highlighting the advance of the American Third Army, commanded by General George Patton. In just three weeks, Patton had covered over 400 miles, with his lead elements now barely a hundred miles from the German frontier. The situation was dire, and von Rundstedt understood the gravity of the moment. After a long pause, he asked the question that weighed heavily on his mind: “What do we have to stop him with?”

Blumentritt’s response was chillingly straightforward: “Nothing.”

The German military situation in early September 1944 was worse than most people today realize. This was not merely a retreat; it was the near-total collapse of German military power in Western Europe. Between Patton’s forward positions and the German border, there were no intact German divisions. The units that had fought in Normandy were either destroyed, scattered, or retreating eastward in varying degrees of panic. Many had abandoned their heavy weapons, leaving them ill-equipped to mount any effective resistance. Those that still retained some semblance of organization were “divisions” only on paper—fragments of 2,000 to 5,000 men where there should have been 17,000, severely lacking in ammunition, fuel, artillery, and morale.

This catastrophic situation led to disbelief among German commanders regarding Patton’s advance. They could not comprehend how a single American general could achieve such rapid success against an enemy that was supposed to be formidable. The German high command had been conditioned to expect fierce resistance from their own troops, but the reality was starkly different. The psychological impact of the Allied successes in Normandy had shattered the confidence of German forces, leading to a crisis of leadership and morale.

As Patton’s Third Army continued its relentless advance, German commanders could only watch helplessly as their once-mighty military apparatus crumbled. The speed of the American advance was unprecedented, catching the Germans off guard. They had anticipated a more drawn-out conflict, one where they could regroup and fortify their positions. Instead, they faced the reality of a rapidly collapsing front.

Compounding this dire situation were logistical challenges. The German supply lines had been stretched thin, and the forces that remained were ill-equipped to sustain a prolonged fight. The Allies had gained air superiority, which further hampered German movements and resupply efforts. As Patton pushed forward, he exploited these weaknesses, using his tanks and mechanized infantry to create breakthroughs that left the Germans reeling.

In this context, German commanders found it difficult to comprehend how Patton could continue his advance unopposed. Their intelligence assessments were flawed, leading them to underestimate the speed and effectiveness of the American response. The belief that they could regroup and mount a counteroffensive was quickly fading, replaced by a growing sense of despair.

As the days passed and Patton’s forces drew closer to the German border, the reality of the situation became undeniable. The German military, once a symbol of strength and discipline, was now a shadow of its former self, struggling to respond to the onslaught of an enemy that had learned to adapt and exploit its weaknesses. The inability of German commanders to believe that Patton could not be stopped was rooted in a combination of overconfidence and a failure to recognize the true state of their own forces.

Ultimately, the events of September 1944 set the stage for the Allied liberation of Western Europe. Patton’s audacious advance not only demonstrated his tactical brilliance but also highlighted the vulnerabilities of a once-dominant military force. The collapse of German defenses in the face of such rapid American progress would lead to significant shifts in the balance of power, paving the way for the eventual Allied victory in World War II.

The disbelief of German commanders in the face of Patton’s relentless advance serves as a stark reminder of how quickly fortunes can change in warfare, often dictated by the courage and resolve of those who dare to seize the initiative. Patton’s ability to inspire his troops and execute bold strategies showcased the effectiveness of leadership in times of crisis. As the war progressed, the lessons learned from this period would shape military strategies and command decisions for generations to come, illustrating the profound impact of decisive action in the theater of war.

News

The Mysterious Disappearance of Tank Crew Charlie 7: How the Vanishing of Three Young Soldiers in 1944 Led to the Discovery of Their Sherman Tank 65 Years Later, Unraveling the Secrets of Their Final Mission in the Foggy Forests of Eastern France

The Enigmatic Disappearance of Tank Crew Charlie 7: A 65-Year Mystery Unveiled In November 1944, three young tank crewmen embarked…

George Patton: The Only General Prepared for the Battle of the Bulge—How His Foresight, Decisive Leadership, and Unwavering Confidence in His Troops Turned the Tide Against the German Offensive and Saved the 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne

George Patton: The General Who Was Ready for the Battle of the Bulge On December 19, 1944, a crucial meeting…

“How a Harrowing Encounter Between Nineteen-Year-Old German Luftwaffe Helferin Anna Schaefer and American Soldier Private First Class Vincent Rossi on a Muddy Roadside in Heilbronn, Germany, Transformed from Terror to Compassion During the Final Days of World War II.

The Humanity of War: A Story of Compassion in Conflict On April 17, 1945, a significant yet harrowing event unfolded…

“How General Patton’s Bold Decision to Launch a Counterattack in Just Three Days Defied Expectations and Turned the Tide at Bastogne During the Battle of the Bulge, While German Generals Underestimated His Capabilities and Miscalculated the Speed of American Forces in December 1944.”

Why German Generals Said Patton’s Rescue Was Impossible On December 19, 1944, in a damp, cold barracks at Verdun, General…

“From ‘Junkyard’ to Success: How Warren Jessup Transformed His Farm and Equipment, Defying Criticism and Inspiring His Community Over a Decade.”

They Called His Tractor and Equipment ‘Junkyard’… Ten Years Later, They Were Selling Theirs The wind off the Kansas plains…

“From Enemies to Allies: How American Lieutenant Daniel O’Connell Transformed a Moment of Fear into Compassion by Sharing Food with German Women POWs After the End of World War II in May 1945.”

“This Is the Best Food I’ve Ever Had” — German Women POWs Tried American Food for The First Time On…

End of content

No more pages to load