Franceska Mann, born Franceska Manheimer on February 4, 1917, in Warsaw, was a brilliant ballerina whose talent illuminated pre-war Poland. Her life, full of grace and promise, was shattered by the Nazi occupation, leading to her tragic end at Auschwitz. Known for her beauty and exceptional skill in ballet and modern dance, Mann’s final act of resistance against her captors has made her a symbol of defiance. This analysis, for history enthusiasts, traces her journey from the stages of Warsaw to the horrors of the Holocaust, highlighting her legacy as a beacon of courage amidst unimaginable adversity.

A Star on the Warsaw Stage

Franceska Mann grew up in the vibrant cultural scene of Warsaw, then part of the Kingdom of Poland. From a young age, she displayed extraordinary talent, studying ballet and contemporary dance with renowned teachers Tacjanna Wysocka and Irena Prusicka. Her repertoire included freestyle dancing, ballet, and tap dancing, earning her recognition as one of Poland’s most promising performers between 1936 and 1939. Mann performed on the stages of the Grand Theatre, opera houses, cabarets, cafés, and revue shows, and even appeared in the short film *Poles Are Famous*. She befriended luminaries such as singer Wiera Gran and actress Stefania Grodzieńska, cementing her place in Warsaw’s artistic circles.

In May 1939, just months before the war, Mann’s international promise shone at the Brussels Dance Competition, where she placed fourth among 125 young dancers with a performance inspired by the ballet sketches of Edgar Degas. Her beauty and poise made her a beloved figure, but the outbreak of World War II on September 1, 1939, with the German invasion of Poland, brought this golden age to an end. Warsaw endured intense bombing, fell on September 29, and the campaign concluded on October 6 with the country divided between Germany and the Soviet Union.

Life in the Warsaw Ghetto

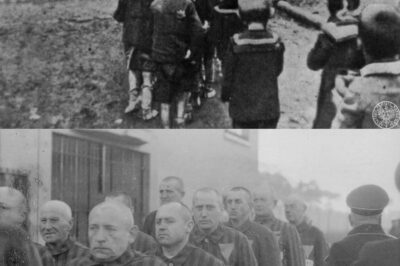

As Nazi persecution intensified, Warsaw’s Jews faced increasing restrictions. On November 23, 1939, they were required to wear white armbands with the blue Star of David. Schools were closed, property confiscated, and men were conscripted for forced labor. On October 12, 1940, the Warsaw Ghetto was established, confining Jews to an area sealed off in November. Mann, her husband Marek Rosenberg, and their young daughter were among those imprisoned there.

Despite the dire conditions, Mann continued to perform at venues such as the Femina Theater, the Melody Palace, and the Café Bagatela, offering fleeting moments of joy and cultural resistance. Her dances provided solace in a place of hunger and despair. The Ghetto Uprising erupted on April 19, 1943, when SS forces moved in to deport the survivors to the Lublin labor camps. Residents fought fiercely for nearly a month, inflicting casualties on well-armed units. Mann’s husband and daughter were killed during this period, leaving her facing the destruction of the ghetto. On May 16, 1943, SS commander Jürgen Stroop reported that “the old Jewish quarter of Warsaw no longer exists,” after razing the area block by block.

Thousands survived in hiding, but Nazi deception lured many to come out. The Hotel Polski affair, a trap promising foreign passports and safe passage to Switzerland, attracted between 2,500 and 3,500 Jews despite warnings from the Polish resistance. Mann, desperate to escape, fell victim to this ruse.

The Final Act of Defiance at Auschwitz

On October 23, 1943, a transport of some 1,700 Jews from the Hotel Polski, including Mann, arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau under the false pretense of being taken to Bergau, near Dresden, to be exchanged for German prisoners of war. Upon arrival, the deception unraveled. Naked and prepared for the gas chambers, Mann seized a moment of resistance. According to survivor accounts, he grabbed an SS officer’s pistol and fired, wounding him and possibly killing another before being overpowered and shot.

This act of rebellion, though unsuccessful in saving his life, symbolized an unbreakable spirit. Mann’s final resistance, rooted in the grace and inner strength of his dancing girl, has been immortalized as a testament to Jewish resilience. His story underscores the human capacity for defiance even in the face of certain death.

Legacy of Grace and Courage

Mann’s life ended tragically at Auschwitz, but her legacy lives on. Celebrated in Polish and Jewish history, she represents the intersection of art and resistance. Monuments and narratives honor her as a ballerina who danced amid adversity and fought back in her final moments. Her story reminds us of the cultural vitality lost with the Holocaust and the quiet heroism that persisted.

Historians see Mann’s actions as emblematic of spontaneous resistance, challenging the narrative of passive victimhood. Her story inspires reflection on the power of individual courage.

Franceska Mann’s journey from celebrated Warsaw dancer to defiant figure at Auschwitz encapsulates the devastation of the Holocaust and human resilience. Her performances illuminated the ghetto, and her final shot echoed the unquenchable will to resist. For history buffs, Mann’s legacy calls us to remember the artists and fighters lost, honoring their grace and courage. Her story urges us to confront hatred with empathy, ensuring that such tragedies are not forgotten or repeated.

News

1 MINUTE AGO: After 88 years, a drone FINALLY captures the location of Amelia Earhart’s plane!

After nearly nine decades of mystery, one of the most enduring enigmas in aviation history may finally be solved. They…

THE FORGOTTEN GAY VICTIMS OF NAZI HELL: The Horrible Medical Experiments and Brutal Persecution, Systematic Torture of Gay Men in Nazi Germany

Content Warning: This article discusses historical persecution, including imprisonment and forced medical procedures, which may be distressing. Its purpose is…

The Final Confessions to the US Army of the Nazi King of Poland: Hans Frank – The Murderous Governor Who Caused 6 Million Deaths Ended in Agony at Nuremberg

Hans Frank (1900–1946), Nazi lawyer and Governor-General of occupied Poland, earned the nickname “Butcher of Poland” for his role in…

IT HAPPENED! A gigantic object 100 times BIGGER than 3I/ATLAS just arrived. And it’s heading straight for it, as if it’s HUNTING something.

In the depths of the cosmos, where stars whisper ancient secrets and shadows stretch beyond imagination, an astronomical event has…

Ten years after the disappearance of young biologist Emily Carter in the white snows of Montana, a group of hikers discovered her body, strangely preserved with beeswax on a stone altar inside an ice cave, surrounded by mysterious symbols and a terrifying humming sound that defies all logic and makes people never look at the mountains the same way again

The mountains of Montana have long been a refuge for those seeking peace, solitude, and answers to their questions. Emily…

“From Hitler’s Trusted Ally to a Grisly End: The Shocking Fall of Karl Hanke, the Ruthless Nazi Leader Beaten to Death and Hung Upside Down by the People He Terrorized”

Karl Hanke: The Rise and Fall of a Ruthless Nazi Leader Karl Hanke (1903–1945) was one of the most prominent…

End of content

No more pages to load