Content Warning: This article discusses historical events related to extreme violence, war crimes, and the Holocaust, which may be distressing. Its purpose is to educate about the atrocities of the Nazi regime and the courage of resistance, encouraging reflection on human rights and genocide prevention.

Rudolf Beckmann (1910–1943), an SS officer and member of the Nazi Party, served in the T4 euthanasia program and later at the Sobibor extermination camp, where he oversaw the sorting of victims’ possessions and administrative duties. As a committed supporter of Nazi racial ideology, Beckmann contributed to the deaths of thousands of people. He was killed on October 14, 1943, during the Sobibor Uprising, a prisoner revolt that led to the camp’s closure. This analysis, based on verified sources such as Wikipedia and the Sobibor Memorial, provides an objective view of Beckmann’s background, his role in the camps and the uprising, to foster debate about the mechanisms of Nazi terror and the importance of remembrance for the victims.

Early Life and Nazi Affiliation

Rudolf Beckmann was born on February 20, 1910, in Osnabrück, Germany, during the era of the German Empire. He completed his basic education and trained in a trade before aligning himself with the Nazi movement. Beckmann joined the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and the SS in the early 1930s, embracing the regime’s racial ideology as a “true believer.” In 1933, after Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor on January 30, Beckmann’s commitment deepened, reflecting the widespread enthusiasm for the party’s promises of national rebirth.

World War II broke out on September 1, 1939, with the invasion of Poland, which drew Beckmann into the SS’s growing network of camps and extermination centers.

Service in the T4 Euthanasia Program

In 1940, Beckmann was assigned to Grafeneck Castle, the first centralized T4 facility for the “euthanasia” program, which systematically murdered institutionalized patients with disabilities. Operating from January to April 1940, Grafeneck killed more than 5,000 people using carbon monoxide gas, disguised as medical treatment. Beckmann’s role included administrative duties and guard duty, which supported the program’s secrecy.

When Grafeneck closed, most of the staff, including Beckmann, moved to Hadamar, another T4 facility. Hadamar, active from 1941 to 1945, gassed more than 10,000 victims, including children and the mentally ill. Beckmann remained there until 1942, contributing to the program’s total of 70,000 deaths. The T4 program, publicly discontinued in 1941, continued secretly, and personnel like Beckmann were reassigned to extermination camps.

Transfer to Sobibor and Role in Operations

In the spring of 1942, Beckmann was sent to Sobibor, the second extermination center of Operation Reinhard near Lublin, Poland. Sobibor, operating from May 1942 to October 1943, murdered approximately 250,000 Jews, mostly from Poland, using carbon monoxide piped from engine exhaust into the gas chambers. Deportations arrived by train, and the victims were selected for immediate gassing; the few selected for the job sorted their belongings.

Beckmann led the sorting command and managed the confiscation of victims’ clothing, valuables, and personal belongings before cremation. He also handled administrative duties and oversaw the care of horses for camp transport. His position gave him authority over the prisoners’ labor, reinforcing the camp’s efficiency during the “Final Solution.”

Sobibor’s secrecy was based on deception: arrivals were told they were in a transit camp, with gas chambers disguised as showers. Beckmann’s role ensured its smooth operation, which contributed to the camp’s death toll.

The Sobibor Uprising and Beckmann’s Death

Sobibor prisoners, aware of their fate through leaks and rumors, organized a revolt led by Alexander Pechersky. On October 14, 1943, some 300 prisoners attacked guards using axes, knives, and smuggled weapons. They killed 10 SS officers and six Ukrainian auxiliaries, including Beckmann, who was stabbed to death in the chaos.

The uprising freed 300 prisoners, of whom between 50 and 70 survived the war. This led the Nazis to dismantle Sobibor, demolishing it to hide evidence. Beckmann, who was 32 at the time of his death, was one of 16 German personnel murdered, marking a rare successful prisoner revolt.

Postwar Legacy

The destruction of Sobibor delayed investigations, but survivor testimonies and excavations revealed its magnitude. The 1943 revolt inspired other uprisings, such as that at Treblinka. Beckmann’s death, though violent, symbolized the victims’ action against oppression.

Historians such as Jules Schelvis point to Beckmann’s role as emblematic of the continuity of T4 personnel to Reinhard, highlighting the regime’s systematic murder.

Rudolf Beckmann’s journey from Osnabrück baker to Sobibor sorter and his death in the 1943 uprising illustrate the machinery of the Holocaust and the prisoners’ defiance. Her roles in T4 and Reinhard contributed to thousands of deaths, but the uprising disrupted the extermination system. For history buffs, Beckmann’s story spurs us to remember the 250,000 victims of Sobibor and to discuss the power of resistance. Verified sources like the Sobibor Memorial encourage human rights education, ensuring that such horrors are confronted and never repeated.

News

DECODING THE MYSTERY: Ancient records reveal that “Torenza” existed before the Common Era: a lost civilization, erased from history, reappeared… twice.

In the depths of forgotten excavations, an ancient secret has emerged to challenge everything we thought we knew about human…

“NASA detects unidentified objects escorting comet 3I/Atlas: panic or revelation?”

In the classified NASA records dated June 12, 2042, lies an event that has shaken the foundations of our understanding…

THE GRIM DEATH OF JAPANESE GENERAL MASAHARU HOMMA – The Prime Culprit of the Bataan Death March That Killed 10,000 People and His Last Words to the Japanese That Will Resonate Through the Millennia.

Content Warning: This article discusses historical events related to war crimes and forced marches that resulted in significant loss of…

THE PRICE OF 300 LIVES: The Horrifying Final Moments of the “King of the Decapitators” – Japan’s Most Notorious War Criminal.

Gunkichi Tanaka, a captain in the Imperial Japanese Army, became famous for his role in the Nanjing Massacre, where he…

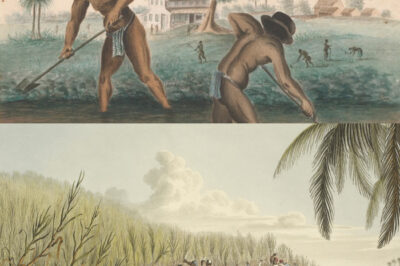

This 1859 plantation portrait looks peaceful—until you see what’s hidden in the slave’s hand.

This 1859 plantation portrait looks peaceful, until you see what’s hidden in the slave’s hand. The Photograph That Shouldn’t Exist…

FINAL WARNING! 3I/ATLAS HAS NO COMET… IT’S AN ALIEN INVASION! — Elon Musk declares to the world: “Humanity must PLAN FOR BATTLE before it’s TOO LATE!”

In the shadows of the cosmos, where science intertwines with the inexplicable, an object has burst into our solar system…

End of content

No more pages to load