Content warning: This article discusses historical events related to violence, occupation, and resistance activities during World War II, which may be distressing. Its aim is to educate about the courage of resistance fighters and the human cost of war, encouraging reflection on human rights and the struggle against oppression.

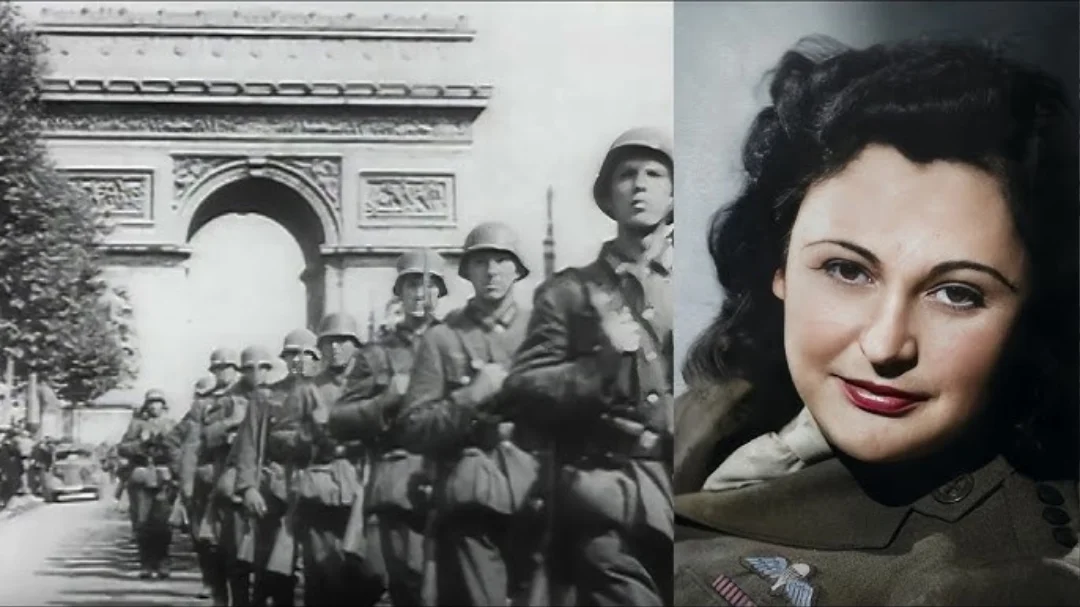

Nancy Wake (1912–2011), born in New Zealand and raised in Australia, became one of the most celebrated Allied agents of World War II. Known as the “White Mouse” for evading capture by the Gestapo, she led the French Resistance, coordinating sabotage and assisting in escapes. Her hatred of Nazism, sparked by witnessing antisemitic violence in Vienna, led her to risk everything. This analysis, based on verified sources such as Wake’s autobiography, The White Mouse, and historical records from the Australian War Memorial, provides an objective account of his life, wartime heroism, and legacy, fostering debate about the power of individual resistance against tyranny.

Early Life and Path to Journalism

Nancy Grace Augusta Wake was born on August 30, 1912, in Wellington, New Zealand, the youngest of six children of Charles Wake, a New Zealand journalist, and Ella Wake. After her parents separated, she moved to Sydney, Australia, at the age of two, raised by her struggling mother. A rebellious spirit, Wake left school at 16 and worked as a nurse’s assistant before inheriting 200 pounds from an aunt, which funded her move to London in 1932.

Determined to escape poverty, Wake took odd jobs before arriving in Paris in 1937 as a correspondent for the Hearst Press. Her fluency in French and her charm opened doors for her in European society. In 1938, she covered the Anschluss, Hitler’s annexation of Austria on March 12, and witnessed Nazi gangs attacking Jews in the streets of Vienna. These scenes of violence against women and children ignited her lifelong hatred of Nazism, transforming her from observer into activist.

Marriage and the Fall of France

In November 1939, Wake married Henri Fiocca, a wealthy Marseilles industrialist from a prominent family, whom she had met in 1937. Their union provided her with stability amidst the shadow of war. World War II began on September 1, 1939, with the German invasion of Poland and ended on October 6 with the Soviet partition.

The Battle of France erupted on May 10, 1940, and Germany invaded France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands within six weeks. Paris fell on June 14, and the armistice of June 22 divided France into occupied and Vichy zones. As a journalist, Wake reported from the front; her marriage to Henri anchored her in occupied Marseille.

Joining the French Resistance

Wake’s fervent anti-Nazi zeal led her to join the Resistance in 1940, using her resources to smuggle food and messages. In 1941, she coordinated escape routes for Allied airmen, Jewish refugees, and downed pilots, earning her a place on the Gestapo’s “most wanted” list. Her nickname, “White Mouse,” stemmed from her ability to evade capture through disguises and quick thinking.

Trained in Britain in 1943, Wake parachuted into occupied France on February 29, 1944, as an SOE agent. Leading 7,000 Maquis fighters in the Auvergne region, she organized sabotage operations, destroying bridges, railways, and German convoys. Her leadership was fearless; she once cycled 300 miles to replace a radio and, during a raid, killed an SS sentry with her bare hands to silence him.

Wake’s ferocity, which earned her the nickname “La Madone aux mitrailleuses” (Madonna with Machine Guns), disrupted German operations before D-Day, aiding the Allied advance.

Postwar Life and Recognition

After liberation, Wake learned that Henri had been tortured and executed by the Gestapo in 1943 for her activities. Devastated, she returned to Australia in 1946 and divorced her second husband, John Forward, in 1950. She worked as a journalist and ran for office, but faced sexism.

Wake received numerous honors: the George Medal, the Croix de Guerre, and the Medal of Freedom. In 2004, at the age of 91, she published her autobiography, The White Mouse. She died on August 7, 2011, at the age of 98, in London, and her ashes were scattered in the Dordogne region.

Legacy and Reflection

Nancy Wake’s story exemplifies individual action against fascism. Her escape and sabotage saved hundreds of lives, disrupting Nazi logistics. Historians like M.R.D. Foot praise her as the most decorated woman in the SOE, symbolizing women’s roles in the resistance.

Her experiences in Vienna highlight the dangers of antisemitism and urge vigilance against discrimination.

Nancy Wake’s transformation from journalist to resistance legend and her postwar humility reflect unwavering courage. From the horrors of Vienna to the battles of the Auvergne, she fought Nazism with her bare hands and an indomitable spirit. For history enthusiasts, Wake’s legacy demands that we remember resistance fighters, discuss human rights, and combat oppression. Verified sources like the Australian War Memorial ensure accurate education, inspiring a world where the courage of such heroes prevents the return of tyranny.

News

The Slave Who Vanished Into the Mountains—Until His Enemies Began to Disappear (1842)

The Slave Who Vanished Into the Mountains—Until His Enemies Began to Disappear (1842) The year was 1842 when a man…

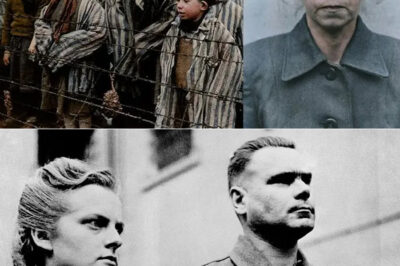

7 Ordinary Women Who Became Evil Nazi Torturers and Living Beasts — The Brutal Concentration Camp Guards You’ve Never Heard About

7 Ordinary Women Who Became Cruel Nazi Torturers: Living Beasts In the shadows of the Holocaust, where Nazi horror reached…

FROM HITLER’S RIGHT HAND TO COWARDICE: The agonizing and tortuous end of Nazi Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel: his last chilling words to the German people before dying on the gallows that will resonate for millennia

Wilhelm Keitel (1882–1946), German field marshal and head of the High Command of the Armed Forces (OKW), was a key…

The master raised his three daughters with his strongest slave… He created his own dynasty

The master raised his three daughters with his strongest slave… he created his own Georgian dynasty in 1852 When it…

“From Rivals to Stewards of Democracy: How a Historic 2009 Oval Office Gathering of Five Presidents Showcased Unity, Respect, and the Enduring Power of America’s Peaceful Transfer of Leadership Amid Crisis and Division”

In January 2009, the United States stood at a crossroads. The nation was grappling with deep political division and the…

On November 22, 1963, Jacqueline Kennedy became a symbol of a nation’s grief. Wearing her pink Chanel suit stained with her husband’s blood, she refused to change, saying, “Let them see what they’ve done to Jack.” Her quiet defiance turned personal tragedy into collective mourning, as she stood beside Lyndon B. Johnson during his oath of office, embodying resilience and loss. The suit, now preserved in the National Archives, remains unseen, a haunting relic of history. Jacqueline’s decision was an act of witness, ensuring the world would never forget the cost of that dark day.

On November 22, 1963, the world was shaken to its core. In Dallas, Texas, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated,…

End of content

No more pages to load