Content Warning: This article discusses historical events related to war crimes and forced marches that resulted in significant loss of life. It is intended to educate about the consequences of military actions and the importance of accountability, and may be distressing for some readers.

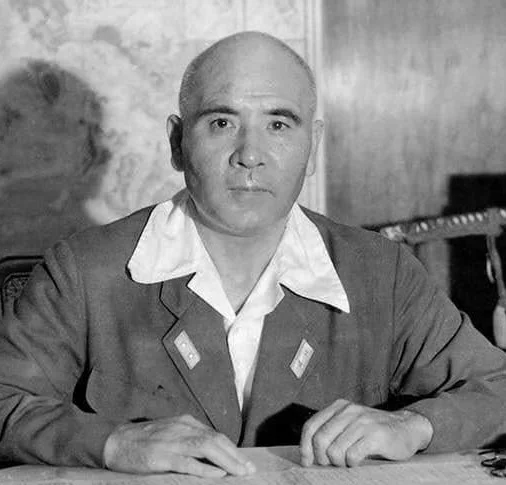

Masahuru Homma (1887–1946), a Japanese general during World War II, commanded the 14th Army in the invasion of the Philippines and oversaw the infamous Bataan Death March in 1942. The march, which involved 75,000 American and Filipino prisoners, resulted in approximately 10,000 deaths from starvation, disease, and execution. Convicted as a war criminal by a U.S. military tribunal in Manila, Homma was executed by firing squad on April 3, 1946. This analysis, based on verified historical sources such as the U.S. National Archives and trial records, provides an objective overview of Homma’s life, military career, role in the Philippine campaign, and trial, in order to foster debate about human rights and the dangers of wartime discrimination.

Early Life and Military Education

Masaharu Homma was born on November 27, 1887, in Sado City, Japan, to a family steeped in military traditions. He graduated from the 19th class of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in May 1907, excelling in strategy and leadership. Three years later, he completed the 27th class of the Army Staff College, honing his advanced tactical skills.

Homma’s fluency in English and admiration for Western culture distinguished him. He studied at Oxford University, served as a military attaché in the United Kingdom for eight years, and earned the Military Cross from the British Expeditionary Force in France during World War I (1914–1918). Nicknamed the “Shogun Poet” for his wartime poems and paintings, Homma combined martial discipline with artistic sensibility, reflecting a nuanced view of the West.

Pre-World War II Career

Homma’s interwar years focused on diplomacy and command. From 1919 to 1927, he served in London, deepening his cultural ties. Upon his return to Japan, he commanded infantry regiments and studied at the Army War College. In the 1930s, as Japan pursued expansion (invading Manchuria in 1931 and escalating conflicts with China), Homma was promoted to major general in 1937 and participated in the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Despite his Western affinity, Homma aligned himself with imperial ambitions, commanding divisions in China and advocating humane treatment in propaganda, although the realities of war often contradicted this.

The Philippine Campaign and the Bataan Death March

The Pacific theater of World War II began with Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Homma led the 14th Army’s invasion of the Philippines on December 8, 1941, capturing Manila on January 2, 1942. Facing fierce Filipino-American resistance, his forces pushed Allied troops back to the Bataan Peninsul

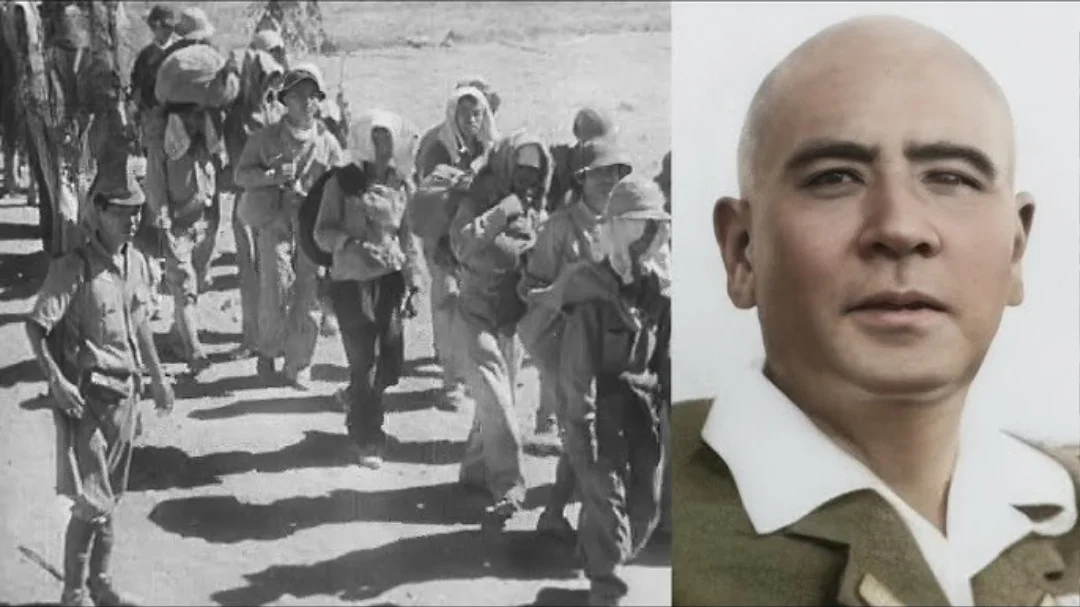

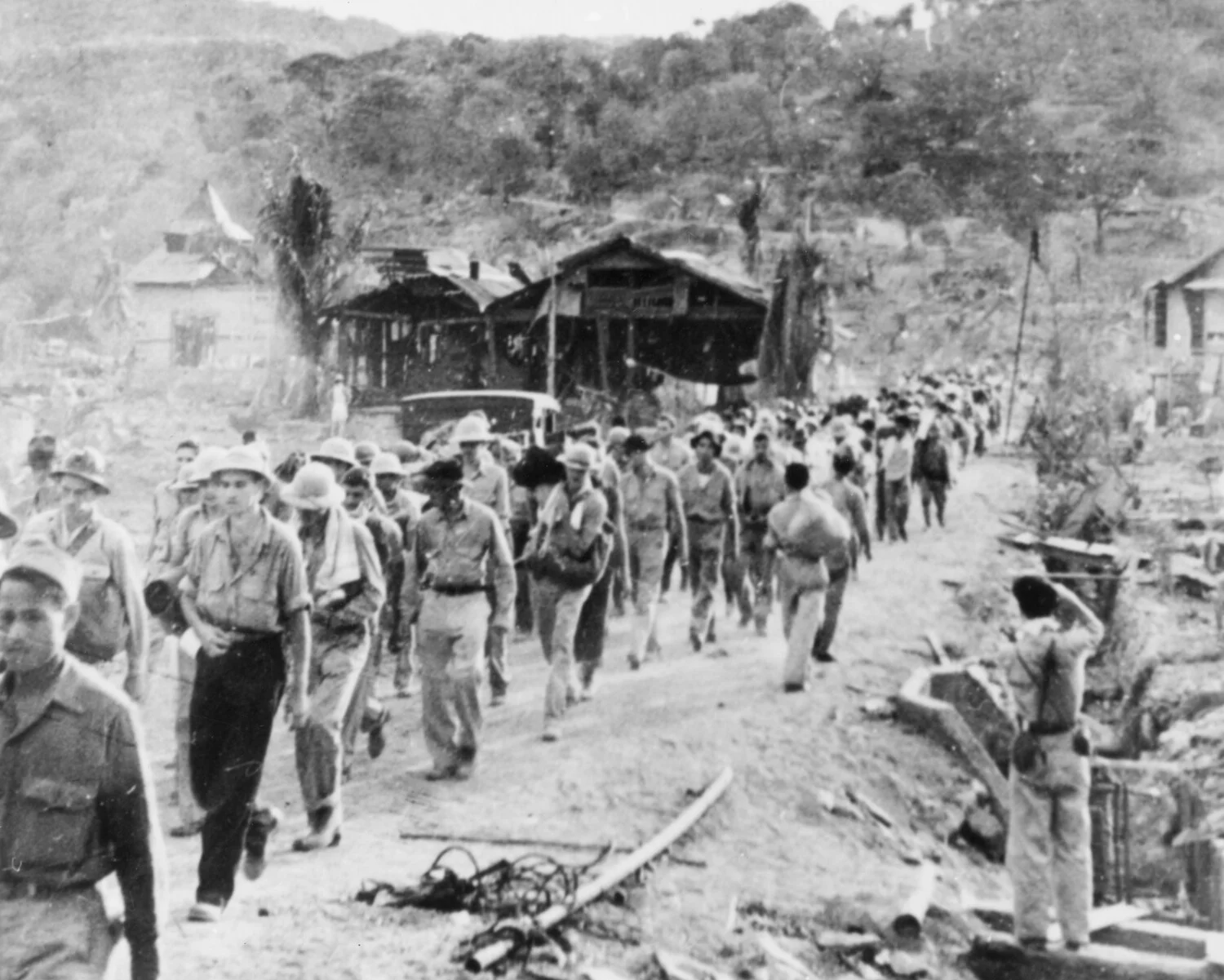

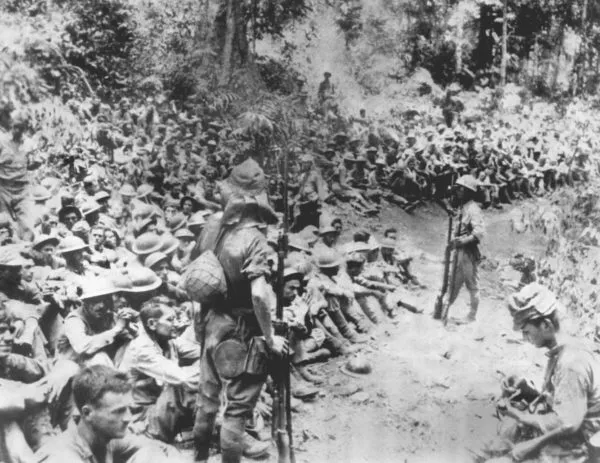

After the fall of Bataan on April 9, 1942, Homma ordered the surrender of 75,000 prisoners (12,000 Americans and 63,000 Filipinos) for a 65-mile march to Camp O’Donnell. Lacking supplies, guards mistreated the prisoners, resulting in 10,000 deaths from exhaustion, malnutrition, disease, and executions. Homma claimed ignorance of the conditions and blamed his subordinates, but court evidence proved his neglect.

The march symbolized Japanese brutality, sparking international outrage and calls for accountability.

Postwar Trial and Execution

Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945. Homma was arrested in September 1945 and tried at the Manila War Crimes Tribunal from January 3 to February 11, 1946, as the first Class A war criminal prosecuted outside Nuremberg.

Accused of violating the laws of war, including murder and inhumane treatment, the tribunal reviewed testimony from survivors, Japanese records, and Homma’s dispatches. It argued that his subordinates acted independently, but the evidence, including his failure to investigate the reports, convicted him on February 11, 1946. Sentenced to death, his appeals were denied.

On April 3, 1946, at the age of 58, Homma was executed by firing squad in Los Baños, Laguna. His last words were: “I am always with the Emperor.” The execution, broadcast live, marked the beginning of postwar justice.

Legacy and Reflection

Homma’s trial set a precedent for prosecuting commanders for the crimes of subordinates, which influenced the Tokyo Trials. His Western upbringing contrasted his wartime role, highlighting the overriding of personal values by ideology. The memory of the Bataan March lives on in memorials such as the Bataan Death March Historical Monument.

Historians debate Homma’s culpability (some see him as a victim of the system, others as an accomplice), but the court’s verdict affirmed the responsibility of the commander.

Masaharu Homma’s life (from cultured officer to Bataan supervisor and execution in 1946) illustrates the moral complexities of war. His trial underscored accountability for atrocities that claimed 10,000 lives and prompted reflection on human rights violations. For history enthusiasts, Homma’s story calls for remembering the victims, discussing the dangers of discrimination, and committing to ethical leadership. By studying verified sources, we honor the past and foster a world free of such horrors.

News

DECODING THE MYSTERY: Ancient records reveal that “Torenza” existed before the Common Era: a lost civilization, erased from history, reappeared… twice.

In the depths of forgotten excavations, an ancient secret has emerged to challenge everything we thought we knew about human…

“NASA detects unidentified objects escorting comet 3I/Atlas: panic or revelation?”

In the classified NASA records dated June 12, 2042, lies an event that has shaken the foundations of our understanding…

THE PRICE OF 300 LIVES: The Horrifying Final Moments of the “King of the Decapitators” – Japan’s Most Notorious War Criminal.

Gunkichi Tanaka, a captain in the Imperial Japanese Army, became famous for his role in the Nanjing Massacre, where he…

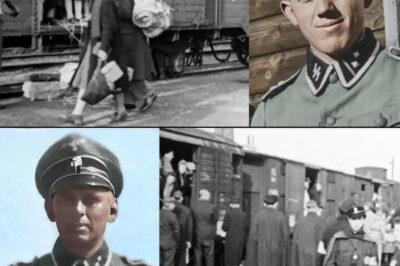

THE DAY A NAZI LEARNED FEAR: Rudolf Beckmann – The Nazi beast of Sobibor screamed in fear as he was murdered by his Jewish victims as he rose up against the concentration camp.

Content Warning: This article discusses historical events related to extreme violence, war crimes, and the Holocaust, which may be distressing….

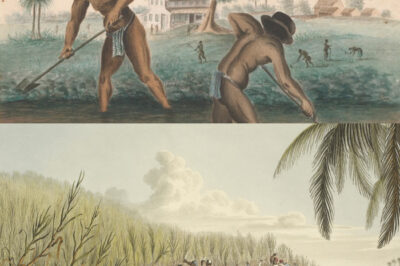

This 1859 plantation portrait looks peaceful—until you see what’s hidden in the slave’s hand.

This 1859 plantation portrait looks peaceful, until you see what’s hidden in the slave’s hand. The Photograph That Shouldn’t Exist…

FINAL WARNING! 3I/ATLAS HAS NO COMET… IT’S AN ALIEN INVASION! — Elon Musk declares to the world: “Humanity must PLAN FOR BATTLE before it’s TOO LATE!”

In the shadows of the cosmos, where science intertwines with the inexplicable, an object has burst into our solar system…

End of content

No more pages to load