The plantation owner’s wife who eloped with a runaway slave: Louisiana’s missing bride of 1847

In the heart of Louisiana’s river region, the cypress swamps of St. James Parish still whisper a name that official records tried to erase: Evelyn Duval. In April 1847, she vanished from her husband’s vast plantation along the Mississippi River. Her disappearance, initially dismissed as a tragic abduction, would become one of the most haunting and enduring mysteries in Louisiana history: a tale of love, rebellion, and silence that has haunted the South for nearly two centuries.

It all began innocently enough. On April 14, 1847, the St. Charles Herald printed a brief notice:

“Missing: Mrs. Evelyn Duval, wife of plantation owner Gerard Duval, last seen the evening of April 10. Reward offered for information leading to her safe return.”

Few readers imagined that this small column, tucked away among advertisements for cotton gins and patented tonics, would unleash a mystery spanning a century.

A Marriage of Appearances

Evelyn arrived in Louisiana from Charleston in 1844, the daughter of a wealthy shipping merchant who arranged her marriage to Gerard Duval, a stern and ambitious sugar planter nearly ten years her senior. Parish records show that Duval had inherited his property in 1839 and, by the middle of the decade, controlled more than one hundred enslaved laborers. The New Orleans Picayune announced their marriage in glowing prose, calling Evelyn “a woman of uncommon beauty and refinement, who will surely bring honor to Louisiana society.”

But Evelyn’s private letters, discovered a century later in a family collection, tell a different story.

“The air here is stifling,” she wrote to a cousin. “The house feels like a museum where I am both exhibitor and visitor.”

She lived behind the glittering facade of the pre-war dream: a life gilded by wealth but imprisoned by its rules.

The Man Named Henry

In January 1846, Duval purchased a man named Henry Carter at the New Orleans slave market. The bill of sale described him as twenty-six years old, literate, skilled in carpentry, and “of sound body and temperament.” An unusual note, believed to have been written by Duval himself, assigned him the task of “managing the organization of the library.”

Soon, Evelyn’s letters changed in tone. She mentioned a man “of uncommon intellect,” someone who “talks of books I thought no one here would know.” Later, neighbors described Mrs. Duval as quiet to the point of being invisible, though her eyes “took in everything.” At Christmas 1846, she seemed distracted and would excuse herself from gatherings mid-conversation.

The Disappearance

On April 10, 1847, Gerard Duval left for New Orleans on business. That night, a heavy rain fell, recorded in the plantation’s weather log. The cook later testified that Mrs. Duval requested tea in the library around eight o’clock. By morning, both Evelyn and Henry were gone.

Duval’s fury was swift. Search parties scoured the swamps, dogs howling through the sugarcane fields. Newspapers from Baton Rouge to Mobile ran the same headline:

“Respected Plantation Wife Kidnapped by Slave.”

A $1,000 reward was offered for Henry, “dead or alive.”

But not everyone believed the story. Rachel, Evelyn’s maid, told authorities that her lover had been secretly packing a small suitcase for days. The statement disappeared from the official records but survived in the parish sheriff’s private notes.

An inventory of Evelyn’s room revealed missing clothing, personal papers, and several volumes of Voltaire and Rousseau. Duval insisted that Henry had stolen them as “proof of his crime.” However, a witness, a riverboat captain, claimed to have seen a veiled woman and a Black man board the boat in the early morning hours of April 11, purchasing passage to New Orleans. “She didn’t seem frightened,” he said. “No more than any woman traveling with a man.”

The Vanishing Trail

From that point on, the record fades. There were unconfirmed rumors that the couple was heading north by sea, perhaps to Haiti, perhaps to Philadelphia. By summer, public interest had waned. Ashamed and embittered, Duval sold his properties and returned to France. Two years later, lightning (or perhaps arson) reduced the plantation to ashes.

Then, for a century, silence.

The Diary in the Wall

In 1958, during renovations of a house in the French Quarter of New Orleans, workers found a sealed tin box inside a wall. Inside was a water-damaged diary inscribed “Property of E.”

The expe

News

THE FATEFUL MOMENT IN THE LIFE OF THE HERO WHO WAS WILLING TO SACRIFICE HIMSELF TO ELIMINATE THE “KILLER MONSTER”: Jan Kubiš – The soldier beheaded by the Nazis for assassinating Reinhard Heydrich – Unwavering until the very last moment.

Content warning: This article discusses historical events related to violence, murder, and execution during World War II, which may be…

THE TOO HIGH PRICE OF 300 LIVES: The terrifying final moments of the “Beheading King” — Japan’s most notorious war criminal… Details below the comments section

Gunkichi Tanaka, a captain in the Imperial Japanese Army, became infamous for his role in the Nanjing Massacre, where he…

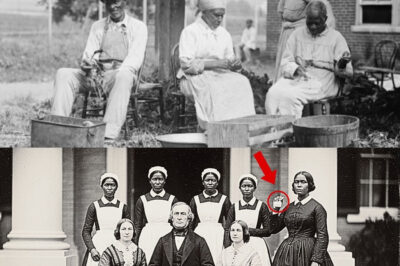

The terrifying truth about this 1859 plantation portrait seems peaceful—until you see what’s hidden in the slave’s hand.

This portrait of a plantation from 1859 seems peaceful, until you see what’s hidden in the slave’s hand. The Photograph…

Solving the mystery of a teenager who disappeared in 1986 — 27 years later a trapdoor was found under an abandoned sheep pen

Disappearance in 1986: A Trapdoor Reveals a Chilling Secret In a quiet rural town in 1986, a seventeen-year-old boy vanished…

She Saved a Helpless Boy in the Storm—Years Later, He Returned as a Billionaire to Rescue Her in Ways Nobody Expected

The night the sky split open over the city, Grace Thompson was just another exhausted soul driving home from her…

When a Mysterious Woman Landed in America, Immigration Officers Expected Routine Paperwork—Until They Discovered Her Passport Was Stamped by a Country No Atlas or History Book Had Ever Recorded. Was It an Elaborate Hoax, a Secret Government Experiment, or Proof of a Parallel World? As experts pored over her documents and questioned her story, the truth unraveled into a mind-bending reality that left scientists, historians, and intelligence agencies in disbelief. What hidden secrets did she bring with her—and could her impossible journey change everything we thought we knew about our world, our borders, and the very nature of reality itself?

The morning rush at JFK International Airport was nothing out of the ordinary—travelers in line, the echo of rolling suitcases,…

End of content

No more pages to load