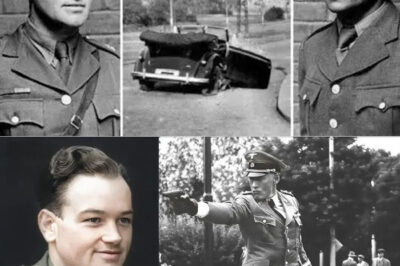

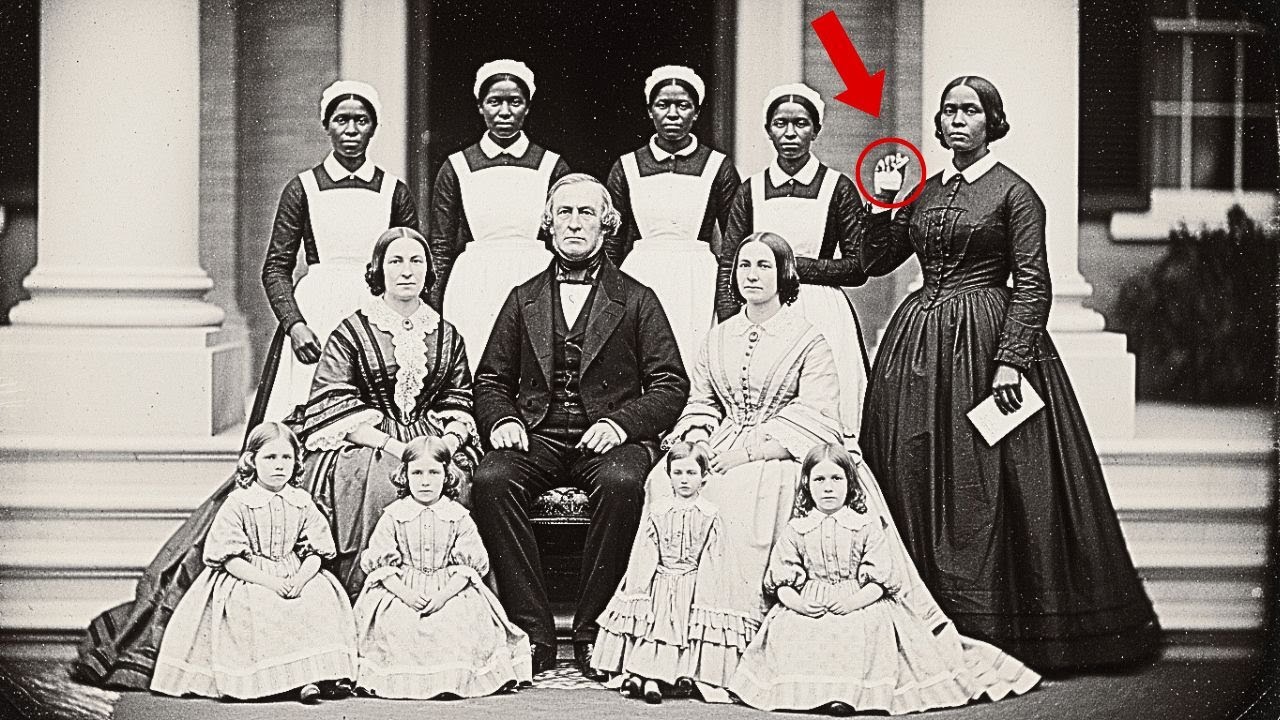

This portrait of a plantation from 1859 seems peaceful, until you see what’s hidden in the slave’s hand.

The Photograph That Shouldn’t Exist

The daguerreotype arrived in an unmarked box: no return address, no note, just a fragile glass plate wrapped in layers of aged paper. Dr. Sarah Mitchell, curator at the Virginia Historical Society, didn’t think much of it at first. She had handled hundreds of 19th-century images. But this one stopped her in her tracks.

The label inside read simply: “Ashford Family, 1859.”

At first glance, it was a typical plantation portrait, one of those carefully staged testaments to wealth and social standing in the pre-war South. The Ashford family of Richmond, Virginia, sat proudly on the steps of their tobacco estate. Master Jonathan Ashford sat in the center, his wife beside him, and their three children arranged like porcelain dolls.

Behind them stood five enslaved servants, posed stiffly, eyes downcast, their presence meant to symbolize luxury, not humanity.

But something about a woman in the background caught Sarah’s eye.

She stood apart, her gaze slightly averted from the others. And in her right hand, half-hidden in the folds of her dress, she held something.

Sarah moved closer, and her breath fogged the glass. It was a folded piece of paper, tightly folded, deliberately so.

Her pulse quickened. Slaves were never allowed to hold anything in portraits like this. Every image was controlled, staged to perfection. And yet, here it was: something secret, intentionally displayed.

“This changes everything,” Sarah whispered in the empty archive room.

The Servant of the Hidden Message

The more Sarah examined the image, the stranger it became. Using a magnifying glass, she could see that the paper wasn’t accidental. It was folded precisely, with crisp creases, as if meant to be read and then hidden again.

That night, she checked the historical records. It turned out that Jonathan Ashford owned Riverside Manor, a sprawling tobacco plantation that employed 47 enslaved people in 1859. He was a member of the Richmond City Council and attended St. John’s Episcopal Church. A man of influence.

The photographer, Marcus Webb, was a traveling daguerreotypist who documented wealthy families in Virginia from 1855 to 1861. Sarah reviewed dozens of his other portraits; none showed servants holding anything. Ever.

The next morning, she called Dr. Marcus Reynolds, a historian specializing in slave resistance movements. When he saw the photograph, he was immediately stunned.

“That’s deliberate,” he said. “He’s holding it perfectly: visible enough for the camera to pick up, but subtle enough that his master would never notice.”

They both stared into the woman’s eyes. She appeared to be in her mid-thirties, tall, intelligent, and fearless. Her face seemed to gaze across time, as if she had planned this moment, knowing that someone, someday, would find it.

Whispers in the Archives

Sarah drove to Richmond, retracing history under the same August sun that had blazed over Virginia 166 years earlier. Riverside Manor was long gone (its grounds swallowed by a highway), but the Confederate Museum still held the Ashford family papers.

In a cramped research room, she found the first clue.

A letter dated September 1859, barely a month after the photograph was taken:

“We have had some troubling incidents,” Jonathan Ashford wrote to his brother in Charleston. “Several of the household servants have been acting peculiarly. I have increased supervision and restricted their movements. Any notions they may have acquired must be eliminated before they spread.”

Sarah’s hands trembled. Something had happened between August and September.

Then, another document: a sales invoice from October 1859. Ashford had sold three women to a merchant bound for New Orleans: Clara, Ruth, and Diane.

The price? Slightly below market value. A hasty sale.

A Descendant’s Memory

Following a lead, Sarah visited Elizabeth Ashford Monroe, an 83-year-old descendant who lives in Richmond’s Fan District.

“My family history isn’t something I’m proud of,” Elizabeth said, adjusting her glasses. “But I believe in facing it.”

When Sarah showed her the photograph, Elizabeth paled.

“I’ve never seen this before,” she murmured. “My grandfather destroyed most of the pictures from that time. He said the past should stay buried.”

When asked why, she hesitated.

“There were rumors, an incident in 1859. My great-great-grandfather believed the servants were up to something. He discovered it just in time, or so the story goes. One woman, Clara, was educated. She had learned

News

THE FATEFUL MOMENT IN THE LIFE OF THE HERO WHO WAS WILLING TO SACRIFICE HIMSELF TO ELIMINATE THE “KILLER MONSTER”: Jan Kubiš – The soldier beheaded by the Nazis for assassinating Reinhard Heydrich – Unwavering until the very last moment.

Content warning: This article discusses historical events related to violence, murder, and execution during World War II, which may be…

THE TOO HIGH PRICE OF 300 LIVES: The terrifying final moments of the “Beheading King” — Japan’s most notorious war criminal… Details below the comments section

Gunkichi Tanaka, a captain in the Imperial Japanese Army, became infamous for his role in the Nanjing Massacre, where he…

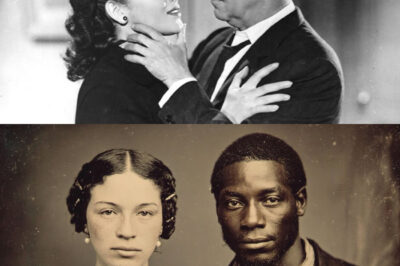

The plantation owner’s wife who eloped with a runaway slave: the Louisiana Missing Bride of 1847

The plantation owner’s wife who eloped with a runaway slave: Louisiana’s missing bride of 1847 In the heart of Louisiana’s…

Solving the mystery of a teenager who disappeared in 1986 — 27 years later a trapdoor was found under an abandoned sheep pen

Disappearance in 1986: A Trapdoor Reveals a Chilling Secret In a quiet rural town in 1986, a seventeen-year-old boy vanished…

She Saved a Helpless Boy in the Storm—Years Later, He Returned as a Billionaire to Rescue Her in Ways Nobody Expected

The night the sky split open over the city, Grace Thompson was just another exhausted soul driving home from her…

When a Mysterious Woman Landed in America, Immigration Officers Expected Routine Paperwork—Until They Discovered Her Passport Was Stamped by a Country No Atlas or History Book Had Ever Recorded. Was It an Elaborate Hoax, a Secret Government Experiment, or Proof of a Parallel World? As experts pored over her documents and questioned her story, the truth unraveled into a mind-bending reality that left scientists, historians, and intelligence agencies in disbelief. What hidden secrets did she bring with her—and could her impossible journey change everything we thought we knew about our world, our borders, and the very nature of reality itself?

The morning rush at JFK International Airport was nothing out of the ordinary—travelers in line, the echo of rolling suitcases,…

End of content

No more pages to load