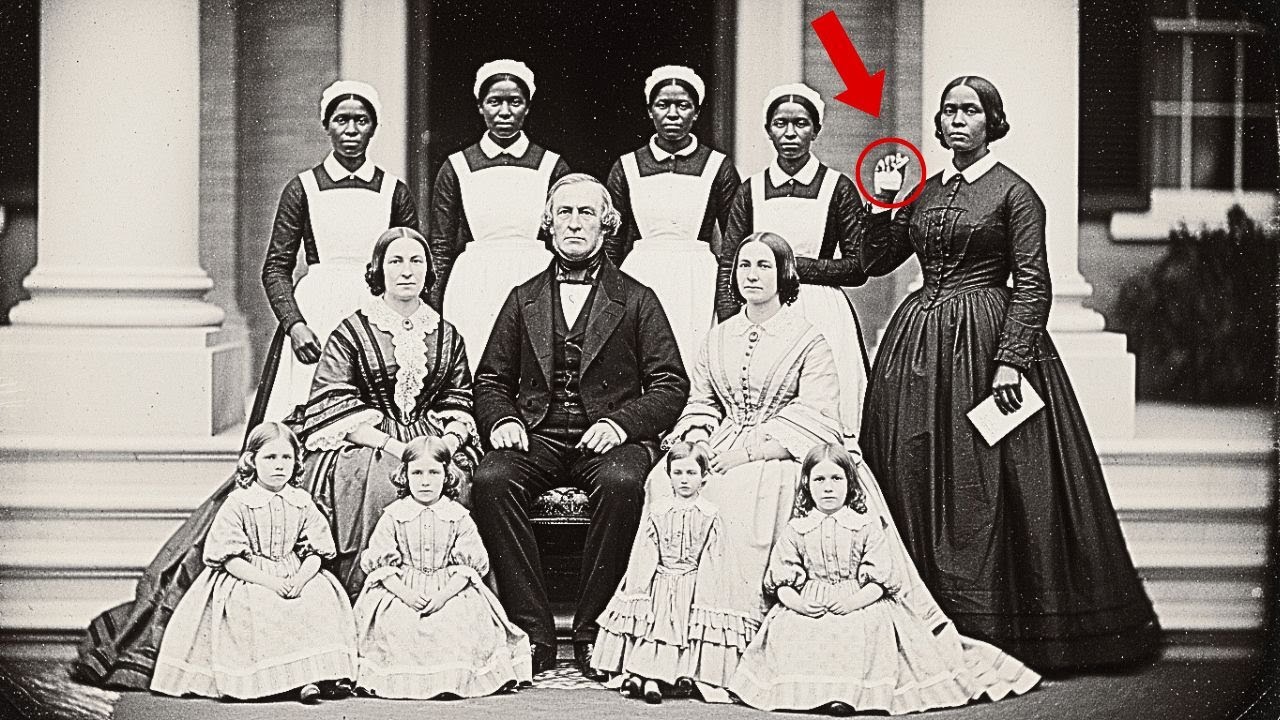

This 1859 plantation portrait looks peaceful, until you see what’s hidden in the slave’s hand.

The Photograph That Shouldn’t Exist

The daguerreotype arrived in an unmarked box: no return address, no note, just a fragile glass plate wrapped in layers of aged paper. Dr. Sarah Mitchell, curator of the Virginia Historical Society, didn’t think much of it at first. She had handled hundreds of 19th-century images before. But this one stopped her in her tracks.

The label inside read only: “Ashford Family, 1859.”

At first glance, it was a typical plantation portrait, one of those carefully staged testaments to wealth and social standing in the antebellum South. The Ashford family of Richmond, Virginia, sat proudly on the steps of their tobacco estate. Master Jonathan Ashford was in the center, his wife at his side, and their three children arranged like porcelain dolls.

Behind them were five enslaved servants, posed stiffly, their eyes lowered, their presence meant to symbolize luxury, not humanity.

But something about a woman in the back caught Sarah’s attention.

She stood back, her gaze slightly averted from the others. And in her right hand, half hidden in the folds of her dress, she held something.

Sarah leaned closer, her breath fogging the glass. It was a piece of paper folded tightly, deliberately.

Her pulse quickened. Slaves were never allowed to hold anything in portraits like this. Each image was controlled, staged to perfection. And yet, here it was: something secret, intentionally shown.

“This changes everything,” Sarah whispered into the empty archive room.

The Servant with the Hidden Message

The more Sarah examined the image, the stranger it became. Using a magnifying glass, she could see that the paper was no accident. It was folded precisely, with crisp creases, as if meant to be read and hidden away again.

That night, she compared the historical records. It turned out that Jonathan Ashford owned Riverside Manor, a sprawling tobacco plantation that employed forty-seven enslaved people in 1859. He was a member of the Richmond city council and attended St. John’s Episcopal Church. A man of influence.

The creator of the photograph, Marcus Webb, was a traveling daguerreotypist who documented wealthy families in Virginia from 1855 to 1861. Sarah reviewed dozens of his other portraits; none showed servants holding anything. Ever.

The next morning, she called Dr. Marcus Reynolds, a historian specializing in slave resistance movements. When he saw the photograph, he immediately froze.

“That’s deliberate,” he said. “She’s holding it perfectly: conspicuous enough for the camera to pick up, but subtle enough that her master will never notice.”

They both stared into the woman’s eyes. She looked to be in her thirties, tall, intelligent, and fearless. Her face seemed to look back through time, as if she had planned this moment knowing that someone, someday, would find it.

Whispers in the Archives

Sarah drove to Richmond, tracing history under the same August sun that had blazed over Virginia 166 years earlier. Riverside Manor was long gone (its grounds swallowed by a highway), but the Museum of the Confederacy still held the Ashford family papers.

In a cramped research room, she found her first clue.

A letter dated September 1859, just a month after the photograph was taken:

“We have had disturbing incidents,” Jonathan Ashford wrote to his brother in Charleston. “Several of the household servants have been acting in a peculiar manner. I have increased supervision and restricted their movements. Any notions they have acquired must be eliminated before they spread.”

Sarah’s hands trembled. Something had happened between August and September.

Then, another document: a bill of sale from October 1859. Ashford had sold three women to a trader bound for New Orleans: Clara, Ruth, and Diane.

The price? Slightly below market value. A hasty sale.

A Descendant’s Memory

Following a lead, Sarah visited Elizabeth Ashford Monroe, an 83-year-old descendant who lives in Richmond’s Fan District.

“My family history isn’t something I’m proud of,” Elizabeth said, adjusting her glasses. “But I believe in facing it.”

When Sarah showed her the photograph, Elizabeth paled.

“I’ve never seen this before,” she murmured. “My grandfather destroyed most of the pictures from that time. He said the past should stay buried.”

When asked why, she hesitated.

“There were rumors, an incident in 1859. My great-great-grandfather believed the servants were up to something. He discovered it just in time, or so the story went. One woman, Clara, was educated. She had learned

News

BEFORE HER 18TH BIRTHDAY, SHE KILLED 100 NAZIS TO AVENGE HER MOTHER: Yefrosinya Zenkova – The Enraged Soviet Teenager Who Eliminated Over 100 Nazis.

Yefrosinya Savelyevna Zenkova (1923–1984) was a Belarusian teenager whose courage as a partisan during World War II made her a…

James Webb detects signs of life aboard the 31 Atlas as the object approaches Earth, shocking scientists around the world.

The James Webb Space Telescope has just revealed its most striking discovery to date, one that challenges everything we thought…

THE SCREAMS OF 60,000 POLISH SOULS ECHOED AT THE EXECUTION: The Horrible Execution of Cowardly Nazis Begging for Mercy After Carrying Out Operation Intelligenzaktion – Massacring Poland’s Intellectuals and Elite.

Content Warning: This article analyzes historical events related to mass executions and ethnic cleansing during World War II, which may…

SIX MONSTROUS WOMEN PAY THE PRICE: The Last Screaming Moments of 6 Nazi Guards – “THE VILE WOMEN OF STUTTHOF” Who Made Victims Tremble at the Mere Mention of Them

The Stutthof concentration camp, established in 1939 near Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland), was a site of Nazi oppression and forced…

La Belle Ballerina, the heroine who shot a Nazi officer at Auschwitz: Facing death with a proud, defiant smile and her terrifying last moments

Franceska Mann, born Franceska Manheimer on February 4, 1917, in Warsaw, was a brilliant ballerina whose talent illuminated pre-war Poland….

1 MINUTE AGO: After 88 years, a drone FINALLY captures the location of Amelia Earhart’s plane!

After nearly nine decades of mystery, one of the most enduring enigmas in aviation history may finally be solved. They…

End of content

No more pages to load