The Decision to Halt: Eisenhower, Patton, and the Elbe River

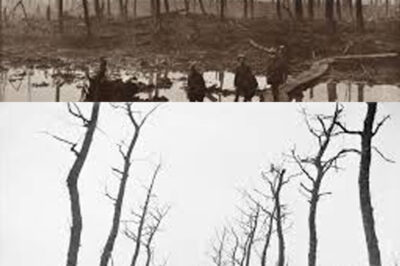

In April 1945, as World War II neared its conclusion in Europe, the atmosphere was fraught with urgency and anticipation. Lieutenant General William Simpson stood on the west bank of the Elbe River, binoculars pressed to his face, staring across the water toward Berlin. Just fifty miles separated his Ninth Army from the German capital, a distance that seemed trivial given the circumstances. Simpson commanded 300,000 well-supplied troops, and German resistance was rapidly crumbling. Soldiers were surrendering en masse, and the Wehrmacht was on the verge of collapse. The opportunity to capture Berlin was ripe, and Simpson believed that with just two days of hard driving, the American flag could soon fly over the Reichstag.

With this in mind, Simpson picked up the field telephone and urgently requested permission from General Omar Bradley to advance toward Berlin. The response, however, was disheartening. Bradley, after consulting with Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower, informed Simpson to halt at the Elbe and not to advance further east. This order left Simpson incredulous. He had witnessed the rapid collapse of German forces and felt the momentum of victory. The road to Berlin was open, yet he was being told to stop completely.

Simpson’s frustration was compounded by the fact that General George Patton, commanding the Third Army to the south, was receiving the same order. Patton, known for his aggressive tactics and relentless pursuit of victory, was equally incensed. He had long argued that capturing Berlin would not only deliver a decisive blow to German morale but also allow the United States to define the post-war order in Europe. He believed that whoever took Berlin would hold the power to influence the future of the continent.

However, Eisenhower’s decision was not made lightly. He was acutely aware of the political ramifications of the war’s outcome and the need to maintain unity among the Allies. The Yalta Conference had established agreements regarding the post-war division of Europe, with Berlin designated as part of the Soviet sphere of influence. Eisenhower understood that advancing into Berlin would risk provoking Stalin and jeopardize the fragile alliance that had been forged among the Allies.

Moreover, intelligence reports about the so-called “National Redoubt” added another layer of complexity to Eisenhower’s decision. Allied intelligence suggested that the Nazis were constructing a massive fortress in the Bavarian and Austrian Alps, where elite SS divisions would make their last stand. Eisenhower feared that allowing American forces to pursue Berlin could lead to a prolonged and costly conflict in the mountains, reminiscent of the brutal battles in Italy. He prioritized the need to eliminate this potential threat over the symbolic victory of capturing Berlin.

As Eisenhower weighed these factors, he ultimately chose diplomatic caution over military opportunity. The decision to halt at the Elbe was made, and American forces were ordered to pivot southward, focusing on locating and destroying the alleged National Redoubt rather than racing the Soviets to Berlin.

The halt at the Elbe left American soldiers feeling frustrated and confused. They watched German civilians fleeing westward, desperate to escape the approaching Soviet forces. The stories they heard from these refugees painted a grim picture of Soviet “liberation,” filled with violence, looting, and retribution. Private James Anderson of the 83rd Infantry Division expressed the sentiments of many when he wrote, “We’re fifty miles from Berlin. We could be there in two days. Instead, we’re sitting on this river watching German civilians run from the Russians. The men are asking why we’re not advancing. I don’t have an answer.”

As the days passed, the soldiers on the Elbe could hear the distant rumble of Soviet artillery pounding Berlin. The battle for the city was raging just beyond the horizon, while the American Army was ordered to remain idle. Some reconnaissance units slipped across the Elbe to probe toward Berlin, hoping for a change in orders, but the command to halt remained in place.

On April 16, 1945, the Soviet assault on Berlin began in earnest, involving 2.5 million troops, thousands of tanks, and a relentless artillery barrage. The scale of the operation was staggering, and the destruction it wrought was catastrophic. From the Elbe, American soldiers could hear the thunder of battle, knowing that they were missing an opportunity to play a decisive role in the war’s conclusion.

As the Soviets captured Berlin on May 2, 1945, the consequences of Eisenhower’s decision became painfully clear. The American forces, who had been so close to the capital, were left to witness the Red Army’s brutal tactics up close. They observed Soviet troops looting and committing atrocities against civilians, reinforcing the fears of what Soviet occupation would mean for Eastern Europe.

In the aftermath, historians and military analysts have debated the implications of Eisenhower’s halt order. Many argue that had American forces advanced to Berlin, they could have potentially changed the post-war landscape in Europe. The presence of American troops in the capital might have altered Soviet ambitions in Eastern Europe, leading to a different balance of power during the Cold War.

The decision to stop at the Elbe not only allowed the Soviets to capture Berlin but also solidified the division of Europe that would last for decades. The line at the Elbe became the western edge of Soviet control, marking the beginning of the Iron Curtain that would divide the continent. General Simpson, reflecting on the events, wrote in his private papers, “We stopped at the Elbe to avoid confrontation with the Russians. Now, I wonder if confrontation in April would have been preferable to what followed.”

Ultimately, the halt at the Elbe remains a pivotal moment in history, illustrating the complex interplay of military strategy, political considerations, and the harsh realities of war. Eisenhower’s choice to prioritize diplomatic caution over military opportunity would have lasting consequences, shaping the post-war order and the geopolitical landscape of Europe for decades to come.

News

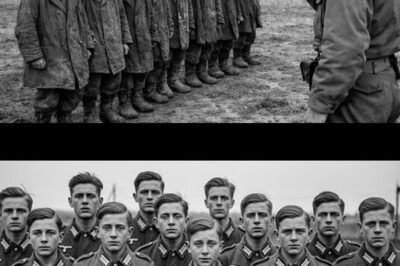

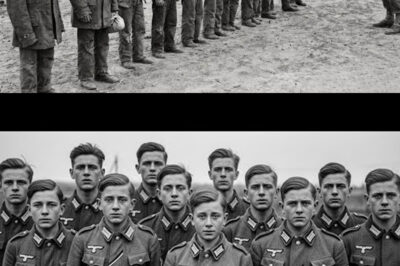

How American Soldiers Chose to Show Kindness by Bringing Hamburgers to German Child Soldiers Facing Execution in the Aftermath of World War II, Transforming a Moment of Fear into an Unforgettable Act of Humanity and Understanding.”

A Hamburger of Hope: The Story of Mercy in the Face of War In April 1945, as World War II…

How an American Soldier’s Compassion for a Starving German Mother and Her Children During Post-War Europe Transformed Their Lives and Highlighted the Power of Humanity Amidst the Devastation of World War II.”

A Simple Act of Kindness: The Lasting Impact of One American Soldier’s Generosity in Post-War Berlin In March 1946, Berlin…

“Exploring the Unique Journey of German Child Soldiers in Post-War Oklahoma: Their Resilience, Struggles with Identity, and Decision to Remain in America After World War II, Highlighting the Impact of Compassion and Community Support in Their Adaptation to Life in a Foreign Land Amidst the Shadows of Their Troubling Past.”

In the aftermath of World War II, the world was left grappling with the consequences of a conflict that had…

“Unraveling the Mysterious Escape of German General Hans von Falkenhausen: The Discovery of His Disguise and Official Papers Generations Later in Forgotten Archives, Shedding Light on His Daring Efforts to Evade Capture at the End of World War II and the Broader Implications for Post-War Justice and Accountability in a Chaotic Europe Struggling to Rebuild After the Devastation of Conflict.”

The Hidden Legacy: Anna Mueller’s Discovery of a Nazi General’s Secret Life In the summer of 2019, Anna Mueller inherited…

“Exploring the Intricacies of Mathematical Formula Formatting: Essential Guidelines for Presenting Complex Equations in a Clear and Structured Manner to Enhance Understanding and Avoid Common Rendering Issues in Various Contexts, While Emphasizing the Importance of Using Block Format for All Mathematical Expressions to Ensure Clarity and Consistency in Communication, and Highlighting the Critical Rules for Effective Presentation Without the Use of Tables, Thus Enabling Readers to Grasp Mathematical Concepts More Effectively and Facilitating Better Engagement with the Material Through Proper Formatting Techniques.”

The Crucial Role of General Patton in the Normandy Campaign: A Turning Point in D-Day Operations The Normandy invasion, known…

“The Forgotten Story of German Child Soldiers in Oklahoma: How Young Boys Refused to Leave America After World War II, Navigating Identity, Trauma, and the Complexities of Belonging in a Foreign Land”

The Journey of Hans Keller: A German Child Soldier’s Story in Oklahoma In the chaotic aftermath of World War II,…

End of content

No more pages to load